In this blog, we’ll take a look at the Log4Shell vulnerability and provide real-world examples of how Darktrace detects and responds to attacks attempting to leverage Log4Shell in the wild.

Log4Shell is now the well-known name for CVE-2021-44228 – a severity 10 zero-day exploiting a well-known Java logging utility known as Log4j. Vulnerabilities are discovered daily, and some are more severe than others, but the fact that this open source utility is nested into nearly everything, including the Mars Ingenuity drone, makes this that much more menacing. Details and further updates about Log4Shell are still emerging at the publication date of this blog.

Typically, zero-days with the power to reach this many systems are held close to the chest and only used by nation states for high value targets or operations. This one, however, was first discovered being used against Minecraft gaming servers, shared in chat amongst gamers.

While all steps should be taken to deploy mitigations to the Log4Shell vulnerability, these can take time. As evidenced here, behavioral detection can be used to look for signs of post-exploitation activity such as scanning, coin mining, lateral movement, and other activities.

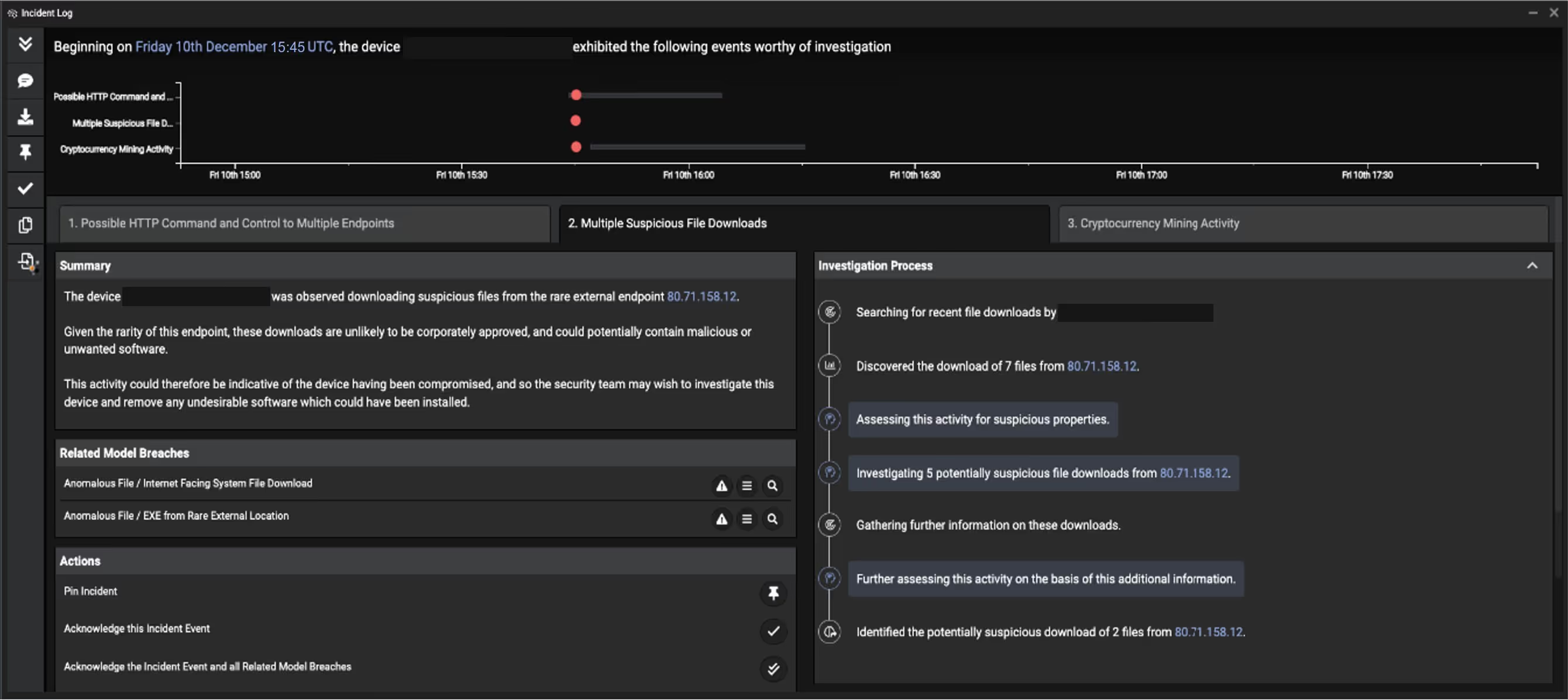

Darktrace initially detected the Log4Shell vulnerability targeting one of our customers’ Internet-facing servers, as you will see in detail in an actual anonymized threat investigation below. This was highlighted and reported using Cyber AI Analyst, unpacked here by our SOC team. Please take note that this was using pre-existing algorithms without retraining classifiers or adjusting response mechanisms in reaction to Log4Shell cyber-attacks.

How Log4Shell works

The vulnerability works by taking advantage of improper input validation by the Java Naming and Directory Interface (JNDI). A command comes in from an HTTP user-agent, encrypted HTTPS connection, or even a chat room message, and the JNDI sends that to the target system in which it gets executed. Most libraries and applications have checks and protections in place to prevent this from happening, but as seen here, they get missed at times.

Various threat actors have started to leverage the vulnerability in attacks, ranging from indiscriminate crypto-mining campaigns to targeted, more sophisticated attacks.

Real-world example 1: Log4Shell exploited on CVE ID release date

Darktrace saw this first example on December 10, the same day the CVE ID was released. We often see publicly documented vulnerabilities being weaponized within days by threat actors. This attack hit an Internet-facing device in an organization’s demilitarized zone (DMZ). Darktrace had automatically classified the server as an Internet-facing device based on its behavior.

The organization had deployed Darktrace in the on-prem network as one of many coverage areas that include cloud, email and SaaS. In this deployment, Darktrace had good visibility of the DMZ traffic. Antigena was not active in this environment, and Darktrace was in detection-mode only. Despite this fact, the client in question was able to identify and remediate this incident within hours of the initial alert. The attack was automated and had the goal of deploying a crypto-miner known as Kinsing.

In this attack, the attacker made it harder to detect the compromise by encrypting the initial command injection using HTTPS over the more common HTTP seen in the wild. Despite this method being able to bypass traditional rules and signature-based systems Darktrace was able to spot multiple unusual behaviors seconds after the initial connection.

Initial compromise details

Through peer analysis Darktrace had previously learned what this specific DMZ device and its peer group normally do in the environment. During the initial exploitation, Darktrace detected various subtle anomalies that taken together made the attack obvious.

- 15:45:32 Inbound HTTPS connection to DMZ server from rare Russian IP — 45.155.205[.]233;

- 15:45:38 DMZ server makes new outbound connection to the same rare Russian IP using two new user agents: Java user agent and curl over a port that is unusual to serve HTTP compared to previous behavior;

- 15:45:39 DMZ server uses an HTTP connection with another new curl user agent (‘curl/7.47.0’) to the same Russian IP. The URI contains reconnaissance information from the DMZ server.

All this activity was detected not because Darktrace had seen it before, but because it strongly deviated from the regular ‘pattern of life’ for this and similar servers in this specific organization.

This server never reached out to rare IP addresses on the Internet, using user agents it never used before, over protocol and port combinations it never uses. Every point-in-time anomaly itself may have presented slightly unusual behavior – but taken together and analyzed in the context of this particular device and environment, the detections clearly tell a bigger story of an ongoing cyber-attack.

Darktrace detected this activity with various models, for example:

- Anomalous Connection / New User Agent to IP Without Hostname

- Anomalous Connection / Callback on Web Facing Device

Further tooling and crypto-miner download

Less than 90 minutes after the initial compromise, the infected server started downloading malicious scripts and executables from a rare Ukrainian IP 80.71.158[.]12.

The following payloads were subsequently downloaded from the Ukrainian IP in order:

- hXXp://80.71.158[.]12//lh.sh

- hXXp://80.71.158[.]12/Expl[REDACTED].class

- hXXp://80.71.158[.]12/kinsing

- hXXp://80.71.158[.]12//libsystem.so

- hXXp://80.71.158[.]12/Expl[REDACTED].class

Using no threat intelligence or detections based on static indicators of compromise (IoC) such as IPs, domain names or file hashes, Darktrace detected this next step in the attack in real time.

The DMZ server in question never communicated with this Ukrainian IP address in the past over these uncommon ports. It is also highly unusual for this device and its peers to download scripts or executable files from this type of external destination, in this fashion. Shortly after these downloads, the DMZ server started to conduct crypto-mining.

Darktrace detected this activity with various models, for example:

- Anomalous File / Script from Rare External Location

- Anomalous File / Internet Facing System File Download

- Device / Internet Facing System with High Priority Alert

Surfacing the Log4Shell incident immediately

In addition to Darktrace detecting each individual step of this attack in real time, Darktrace Cyber AI Analyst also surfaced the overarching security incident, containing a cohesive narrative for the overall attack, as the most high-priority incident within a week’s worth of incidents and alerts in Darktrace. This means that this incident was the most obvious and immediate item highlighted to human security teams as it unfolded. Darktrace’s Cyber AI Analyst found each stage of this incident and asked the very questions you would expect of your human SOC analysts. From the natural language report generated by the Cyber AI Analyst, a summary of each stage of the incident followed by the vital data points human analysts need, is presented in an easy to digest format. Each tab signifies a different part of this incident outlining the actual steps taken during each investigative process.

The result of this is no sifting through low-level alerts, no need to triage point-in-time detections, no putting the detections into a bigger incident context, no need to write a report. All of this was automatically completed by the AI Analyst saving human teams valuable time.

The below incident report was automatically created and could be downloaded as a PDF in various languages.

Figure 1: Darktrace’s Cyber AI Analyst surfaces multiple stages of the attack and explains its investigation process

Real-world example 2: Responding to a different attack using Log4Shell

On December 12, another organization’s Internet-facing server was initially compromised via Log4Shell. While the details of the compromise are different – other IoCs are involved – Darktrace detected and surfaced the attack similarly to the first example.

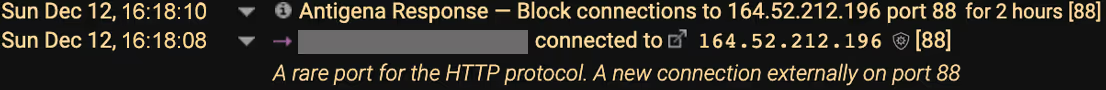

Interestingly, this organization had Darktrace Antigena in autonomous mode on their server, meaning the AI can take autonomous actions to respond to ongoing cyber-attacks. These responses can be delivered via a variety of mechanisms, for instance, API interactions with firewalls, other security tools, or native responses issued by Darktrace.

In this attack the rare external IP 164.52.212[.]196 was used for command and control (C2) communication and malware delivery, using HTTP over port 88, which was highly unusual for this device, peer group and organization.

Antigena reacted in real time in this organization, based on the specific context of the attack, without any human in the loop. Antigena interacted with the organization’s firewall in this case to block any connections to or from the malicious IP address – in this case 164.52.212[.]196 – over port 88 for 2 hours with the option of escalating the block and duration if the attack appears to persist. This is seen in the illustration below:

Figure 2: Antigena’s response

Here comes the trick: thanks to Self-Learning AI, Darktrace knows exactly what the Internet-facing server usually does and does not do, down to each individual data point. Based on the various anomalies, Darktrace is certain that this represents a major cyber-attack.

Antigena now steps in and enforces the regular pattern of life for this server in the DMZ. This means the server can continue doing whatever it normally does – but all the highly anomalous actions are interrupted as they occur in real time, such as speaking to a rare external IP over port 88 serving HTTP to download executables.

Of course the human can change or lift the block at any given time. Antigena can also be configured to be in human confirmation mode, having the human in the loop at certain times during the day (e.g. office hours) or at all times, depending on an organization’s needs and requirements.

Conclusion

This blog illustrates further aspects of cyber-attacks leveraging the Log4Shell vulnerability. It also demonstrates how Darktrace detects and responds to zero-day attacks if Darktrace has visibility of the attacked entities.

While Log4Shell is dominating the IT and security news, similar vulnerabilities have surfaced in the past and will appear in the future. We’ve spoken about our approach to detecting and responding to similar vulnerabilities and surrounding cyber-attacks before, for instance:

- the recent Gitlab vulnerability;

- the ProxyShell Exchange Server vulnerabilities when they were still a zero-day;

- and the Citrix Netscaler vulnerability.

As always, companies should aim for a defense-in-depth strategy combining preventative security controls with detection and response mechanisms, as well as strong patch management.

Thanks to Brianna Leddy (Darktrace’s Director of Analysis) for her insights on the above threat find.