The cyber-criminals behind email attacks are well-researched and highly responsive to human behaviors and emotions, often seeking to evoke a specific reaction by leveraging topical information and current news. It’s therefore no surprise that attackers have attempted to latch onto COVID-19 in their latest effort to convince users to open their emails and click on seemingly benign links.

The latest email trend involves attackers who claim to be from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, purporting to have emergency information about COVID-19. This is typical of a recent trend we’re calling ‘fearware’: cyber-criminals exploit a collective sense of fear and urgency, and coax users into clicking a malicious attachment or link. While the tactic is common, the actual campaigns contain terms and content that’s unique. There are a few patterns in the emails we’ve seen, but none reliably predictable enough to create hard and fast rules that will stop emails with new wording without causing false positives.

For example, looking for the presence of “CDC” in the email sender would easily fail when the emails begin to use new wording, like “WHO”. We’ve also seen a mismatch of links and their display text – with display text that reads “https://cdc.gov/[random-path]” while the actual link is a completely arbitrary URL. Looking for a pattern match on this would likely lead to false positives and would serve as a weak indicator at best.

The majority of these emails, especially the early ones, passed most of our customers’ existing defenses including Mimecast, Proofpoint, and Microsoft’s ATP, and were approved to be delivered directly to the end user’s inbox. Fortunately, these emails were immediately identified and actioned by Antigena Email, Darktrace’s Autonomous Response technology for the inbox.

Gateways: The Current Approach

Most organizations employ Secure Email Gateways (SEGs), like Mimecast or Proofpoint, which serve as an inline middleman between the email sender and the recipient’s email provider. SEGs have largely just become spam-detection engines, as these emails are obvious to spot when seen at scale. They can identify low-hanging fruit (i.e. emails easily detectable as malicious), but they fail to detect and respond when attacks become personalized or deviate even slightly from previously-seen attacks.

Figure 1: A high-level diagram depicting an Email Secure Gateway’s inline position.

SEGs tend to use lists of ‘known-bad’ IPs, domains, and file hashes to determine an email’s threat level – inherently failing to stop novel attacks when they use IPs, domains, or files which are new and have not yet been triaged or reported as malicious.

When advanced detection methods are used in gateway technologies, such as anomaly detection or machine learning, these are performed after the emails have been delivered, and require significant volumes of near-identical emails to trigger. The end result is very often to take an element from one of these emails and simply deny-list it.

When a SEG can’t make the determination on these factors, they may resort to a technique known as sandboxing, which creates an isolated environment for testing links and attachments seen in emails. Alternatively, they may turn to basic levels of anomaly detection that are inadequate due to their lack of context of data outside of emails. For sandboxing, most advanced threats now typically employ evasion techniques like an activation time that waits until a certain date before executing. When deployed, the sandboxing attempts see a harmless file, not recognizing the sleeping attack waiting within.

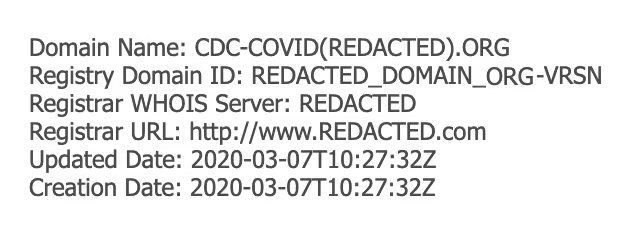

Figure 2: This email was registered only 2 hours prior to an email we processed.

Taking a sample COVID-19 email seen in a Darktrace customer’s environment, we saw a mix of domains used in what appears to be an attempt to avoid pattern detection. It would be improbable to have the domains used on a list of ‘known-bad’ domains anywhere at the time of the first email, as it was received a mere two hours after the domain was registered.

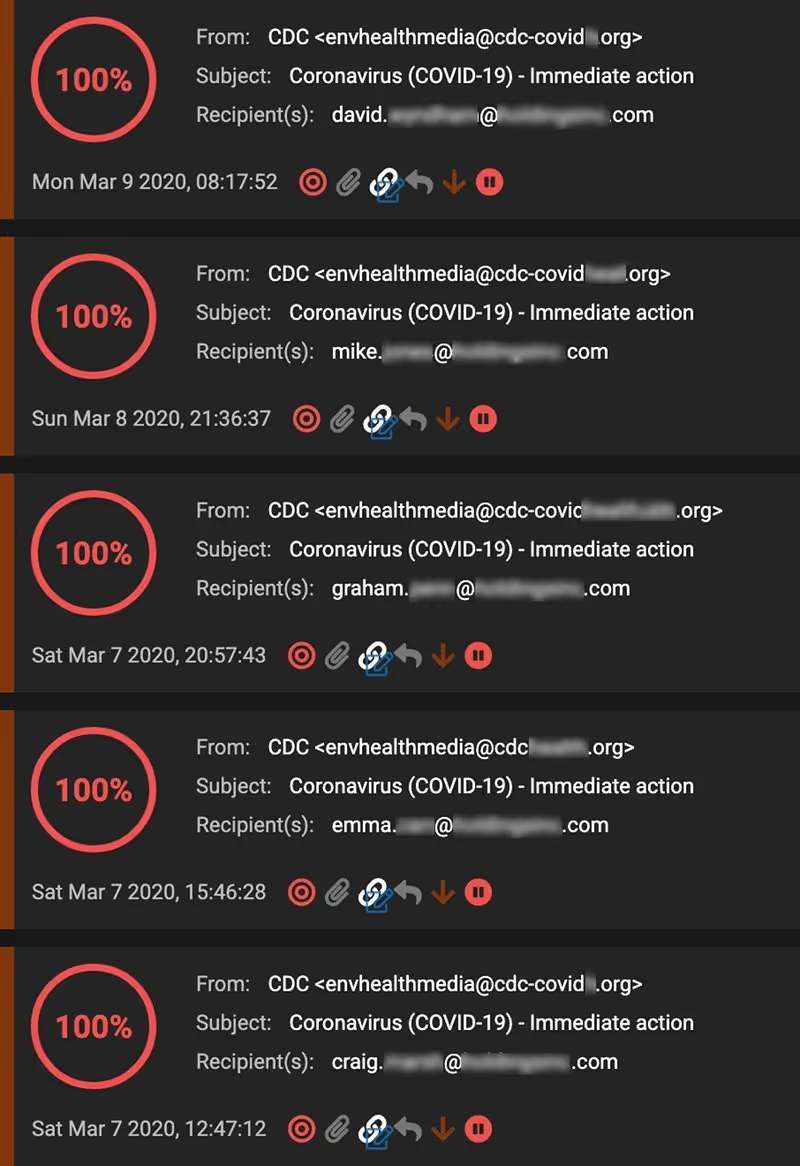

Figure 3: While other defenses failed to block these emails, Antigena Email immediately marked them as 100% unusual and held them back from delivery.

Antigena Email sits behind all other defenses, meaning we only see emails when those defenses fail to block a malicious email or deem an email is safe for delivery. In the above COVID-19 case, the first 5 emails were marked by MS ATP with a spam confidence score of 1, indicating Microsoft scanned the email and it was determined to be clean – so Microsoft took no action whatsoever.

The Cat and Mouse Game

Cyber-criminals are permanently in flux, quickly moving to outsmart security teams and bypass current defenses. Recognizing email as the easiest entry point into an organization, they are capitalizing on the inadequate detection of existing tools by mass-producing personalized emails through factory-style systems that machine-research, draft, and send with minimal human interaction.

Domains are cheap, proxies are cheap, and morphing files slightly to change the entire fingerprint of a file is easy – rendering any list of ‘known-bads’ as outdated within seconds.

Cyber AI: The New Approach

A new approach is required that relies on business context and an inside-out understanding of a corporation, rather than analyzing emails in isolation.

An Immune System Approach

Darktrace’s core technology uses AI to detect unusual patterns of behavior in the enterprise. The AI is able to do this successfully by following the human immune system’s core principles: develop an innate sense of ‘self’, and use that understanding to detect abnormal activity indicative of a threat.

In order to identify threats across the entire enterprise, the AI is able to understand normal patterns of behavior beyond just the network. This is crucial when working towards a goal of full business understanding. There’s a clear connection between activity in, for example, a SaaS application and a corresponding network event, or an event in the cloud and a corresponding event elsewhere within the business.

There’s an explicit relationship between what people do on their computers and the emails they send and receive. Having the context that a user has just visited a website before they receive an email from the same domain lends credibility to that email: it’s very common to visit a website, subscribe to a mailing list, and then receive an email within a few minutes. On the contrary, receiving an email from a brand-new sender, containing a link that nobody in the organization has ever been to, lends support to the fact that the link is likely no good and that perhaps the email should be removed from the user’s inbox.

Enterprise-Wide Context

Darktrace’s Antigena Email extends this interplay of data sources to the inbox, providing unique detection capabilities by leveraging full business context to inform email decisions.

The design of Antigena Email provides a fundamental shift in email security – from where the tool sits to how it understands and processes data. Unlike SEGs, which sit inline and process emails only as they first pass through and never again, Antigena Email sits passively, ingesting data that is journaled to it. The technology doesn’t need to wait until a domain is fingerprinted or sandboxed, or until it is associated with a campaign that has a famous name and all the buzz.

Antigena Email extends its unique position of not sitting inline to email re-assessment, processing emails millions of times instead of just once, enabling actions to be taken well after delivery. A seemingly benign email with popular links may become more interesting over time if there’s an event within the enterprise that was determined to have originated via an email, perhaps when a trusted site becomes compromised. While Antigena Network will mitigate the new threat on the network, Antigena Email will neutralize the emails that contain links associated with those found in the original email.

Figure 4: Antigena Email sits passively off email providers, continuously re-assessing and issuing updated actions as new data is introduced.

When an email first arrives, Antigena Email extracts its raw metadata, processes it multiple times at machine speed, and then many millions of times subsequently as new evidence is introduced (typically based on events seen throughout the business). The system corroborates what it is seeing with what it has previously understood to be normal throughout the corporate environment. For example, when domains are extracted from envelope information or links in the email body, they’re compared against the popularity of the domain on the company’s network.

Figure 5: The link above was determined to be 100% rare for the enterprise.

Dissecting the above COVID-19 linked email, we can extract some of the data made available in the Antigena Email user interface to see why Darktrace thought the email was so unusual. The domain in the ‘From’ address is rare, which is supplemental contextual information derived from data across the customer’s entire digital environment, not limited to just email but including network data as well. The emails’ KCE, KCD, and RCE indicate that it was the first time the sender had been seen in any email: there had been no correspondence with the sender in any way, and the email address had never been seen in the body of any email.

Figure 6: KCE, KCD, and RCE scores indicate no sender history with the organization.

Correlating the above, Antigena Email deemed these emails 100% anomalous to the business and immediately removed them from the recipients’ inboxes. The platform did this for the very first email, and every email thereafter – not a single COVID-19-based email got by Antigena Email.

Conclusion

Cyber AI does not distinguish ‘good’ from ‘bad’; rather whether an event is likely to belong or not. The technology looks only to compare data with the learnt patterns of activity in the environment, incorporating the new email (alongside its own scoring of the email) into its understanding of day-to-day context for the organization.

By asking questions like “Does this email appear to belong?” or “Is there an existing relationship between the sender and recipient?”, the AI can accurately discern the threat posed by a given email, and incorporate these findings into future modelling. A model cannot be trained to think just because the corporation received a higher volume of emails from a specific sender, these emails are all of a sudden considered normal for the environment. By weighing human interaction with the emails or domains to make decisions on math-modeling reincorporation, Cyber AI avoids this assumption, unless there’s legitimate correspondence from within the corporation back out to the sender.

The inbox has traditionally been the easiest point of entry into an organization. But the fundamental differences in approach offered by Cyber AI drastically increase Antigena Email’s detection capability when compared with gateway tools. Customers with and without email gateways in place have therefore seen a noticeable curbing of their email problem. In the continuous cat-and-mouse game with their adversaries, security teams augmenting their defenses with Cyber AI are finally regaining the advantage.

![Pivoting off the previous event by filtering the timeline to events within the same window using timestamp: [“2026-02-18T09:09:00Z” TO “2026-02-18T09:12:00Z”].](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/69a8a18526ca3e653316a596_Screenshot%202026-03-04%20at%201.17.50%E2%80%AFPM.png)