On countless occasions, Darktrace has observed cyber-attacks disrupting business operations by using a vulnerable internet-facing asset as a starting point for infection. Finding that one entry point could be all a threat actor needs to compromise an entire organization. With the objective to prevent such vulnerabilities from being exploited, Darktrace’s latest product family includes Attack Surface Management (ASM) to continuously monitor customer attack surfaces for risks, high-impact vulnerabilities and potential external threats.

An attack surface is the sum of exposed and internet-facing assets and the associated risks a hacker can exploit to carry out a cyber-attack. Darktrace / Attack Surface Management uses AI to understand what external assets belong to an organization by searching beyond known servers, networks, and IPs across public data sources.

This blog discusses how Darktrace / Attack Surface Management could combine with Darktrace / NETWORK to find potential vulnerabilities and subsequent exploitation within network traffic. In particular, this blog will investigate the assets of a large Australian company which operates in the environmental sciences industry.

Introducing ASM

In order to understand the link between PREVENT and DETECT, the core features of ASM should first be showcased.

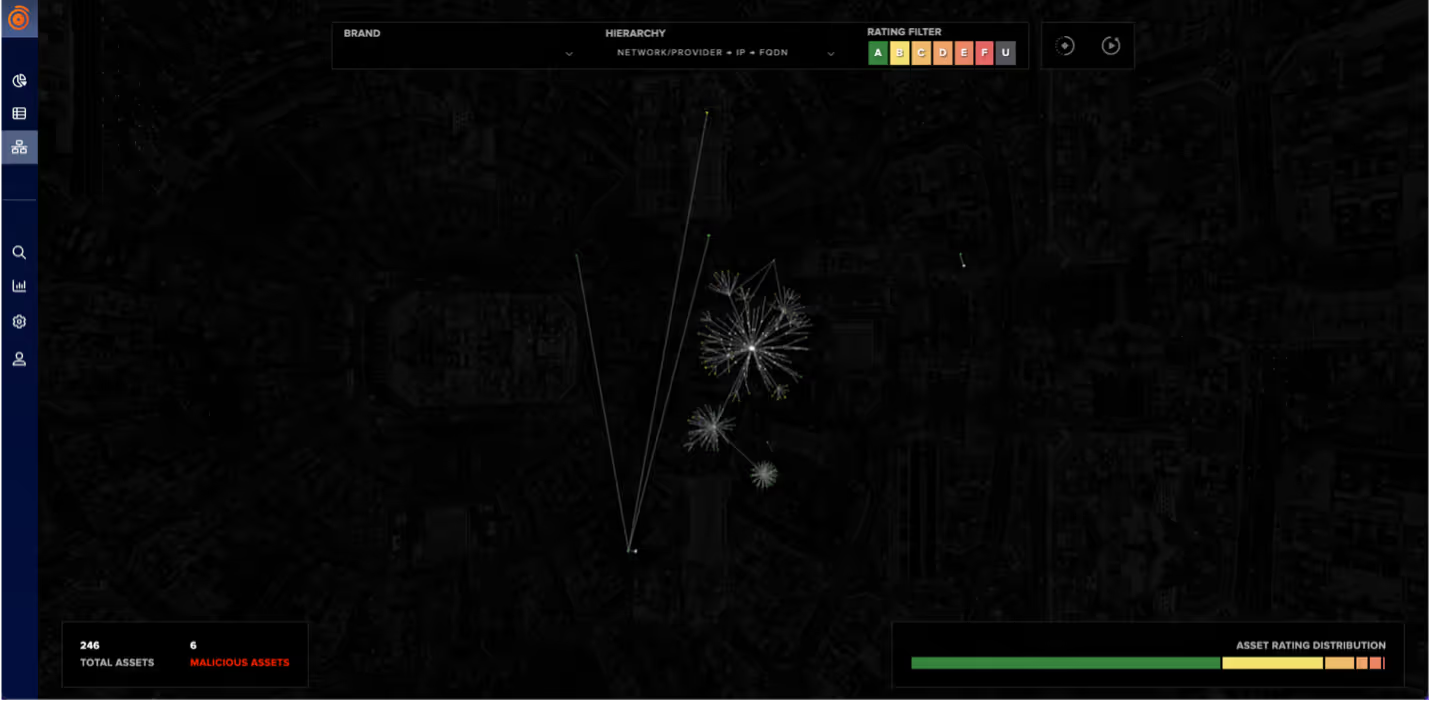

When facing the landing page, the UI highlights the number of registered assets identified (with zero prior deployment). The tool then organizes the information gathered online in an easily assessable manner. Analysts can see vulnerable assets according to groupings like ‘Misconfiguration’, ‘Social Media Threat’ and ‘Information Leak’ which shows the type of risk posed to said assets.

The Network tab helps analysts to filter further to take more rapid action on the most vulnerable assets and interact with them to gather more information. The image below has been filtered by assets with the ‘highest scoring’ risk.

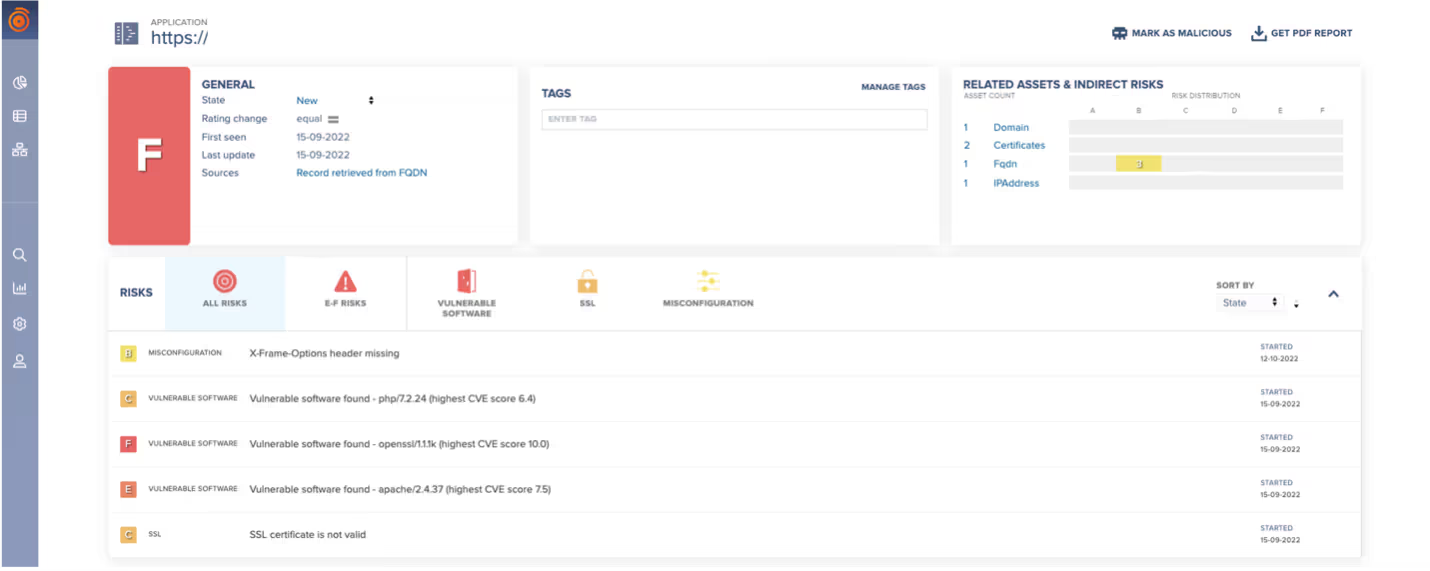

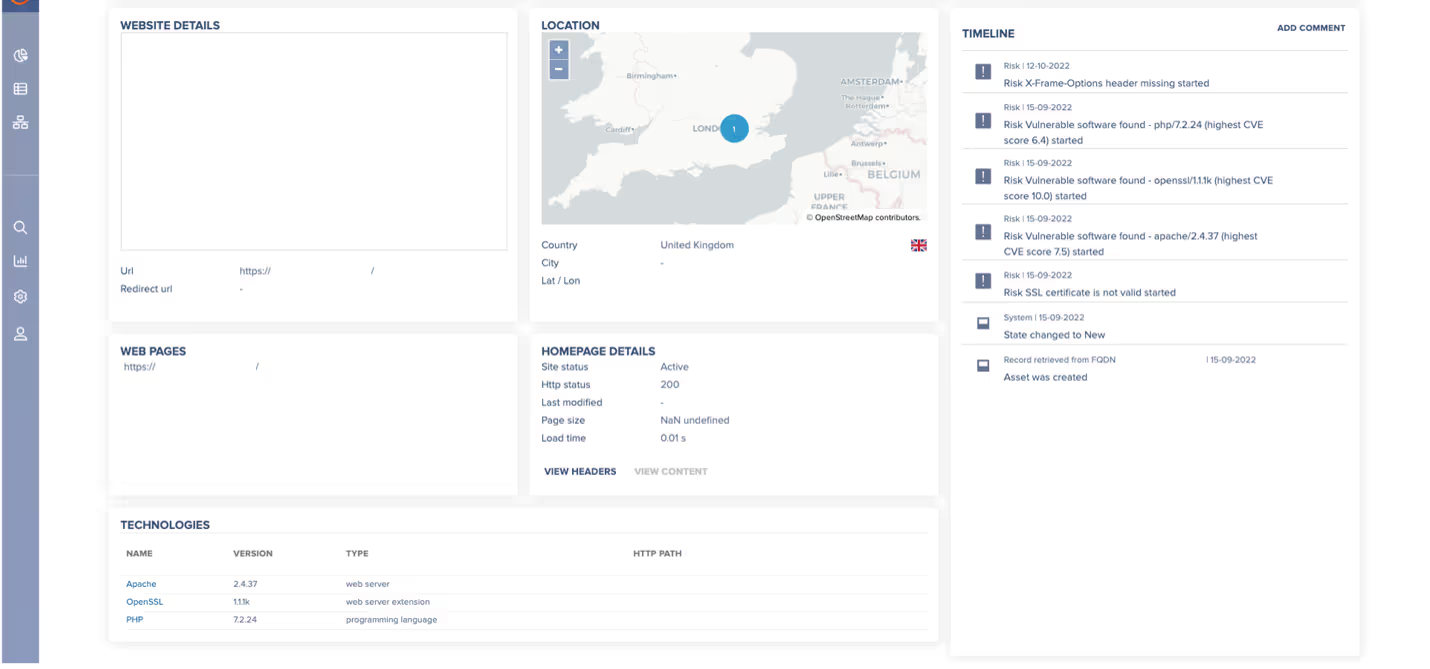

Interacting with the showcased asset selected above allows pivoting to the following page, this provides more granular information around risk metrics and the asset itself. This includes a more detailed description of what the vulnerabilities are, as well as general information about the endpoint including its location, URL, web status and technologies used.

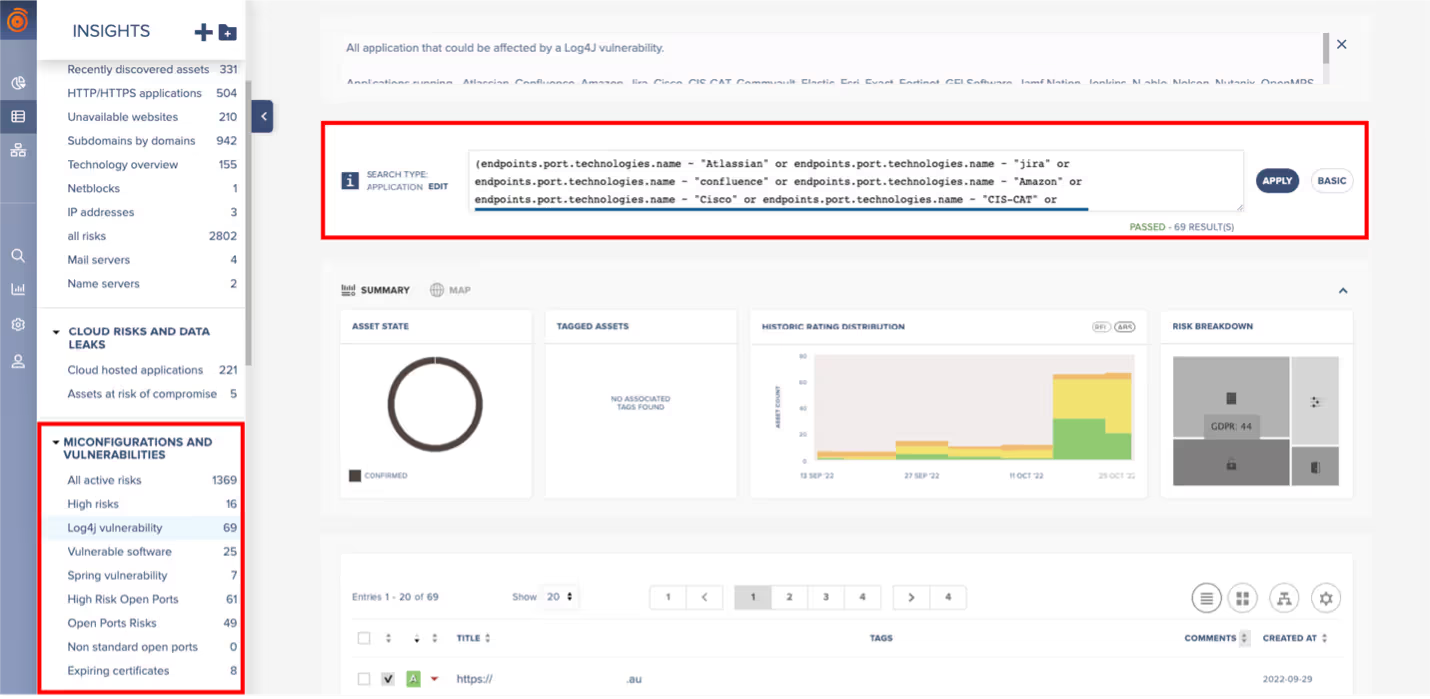

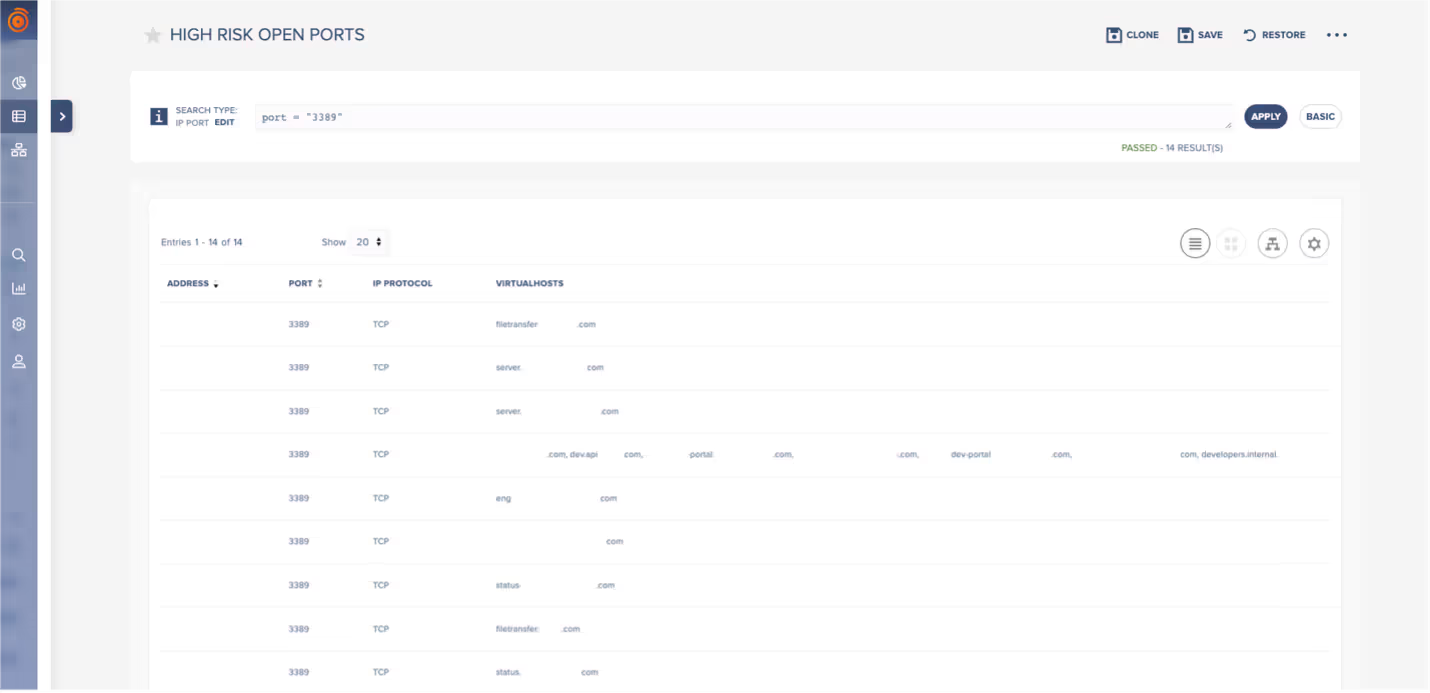

Filtering does not end here. Within the Insights tab, analysts can use the search bar to craft personalized queries and narrow their focus to specific types of risk such as vulnerable software, open ports, or potential cybersquatting attempts from malicious actors impersonating company brands. Likewise, filters can be made for assets that may be running software at risk from a new CVE.

For each of the entries that can be read on the left-hand side, a query that could resemble the one on the top right exists. This allows users to locate specific findings beyond those risks that are categorized as critical. These broader searches can range from viewing the inventory as a whole, to seeing exposed APIs, expiring certificates, or potential shadow IT. Queries will return a list with all the assets matching the given criteria, and users can then explore them further by viewing the asset page as seen in Figure 4.

Compromise Scenario

Now that a basic explanation of PREVENT/ASM has been given, this scenario will continue to look at the Australian customer but show how Darktrace can follow a potential compromise of an at-risk ASM asset into the network.

Having certain ports open could make it particularly easy for an attacker to access an internet-facing asset, particularly those sensitive ones such as 3389 (RDP), 445 (SMB), 135 (RPC Epmapper). Alternatively, a vulnerable program with a well-known exploitation could also aid the task for threat actors.

In this specific case, PREVENT/ASM identified multiple external assets that belonged to the customer with port 3389 open. One of these assets can be labelled as ‘Server A'. Whilst RDP connections can be protected with a password for a given user, if those were weak to bruteforce, it could be an easy task for an attacker to establish an admin session remotely to the victim machine.

N or zero-day vulnerabilities associated with the protocol could also be exploited; for example, CVE-2019-0708 exploits an RCE vulnerability in Remote Desktop where an unauthenticated attacker connects to the target system using RDP and sends specially crafted requests. This vulnerability is pre-authentication and requires no user interaction.

Certain protocols are known to be sensitive according to the control they provide on a destination machine. These are developed for administrative purposes but have the potential to ease an attacker’s job if accessible. Thanks to PREVENT/ASM, security teams can anticipate such activity by having visibility over those assets that could be vulnerable. If this RDP were successfully exploited, DETECT/Network would then highlight the unusual activity performed by the compromised device as the attacker moved through the kill chain.

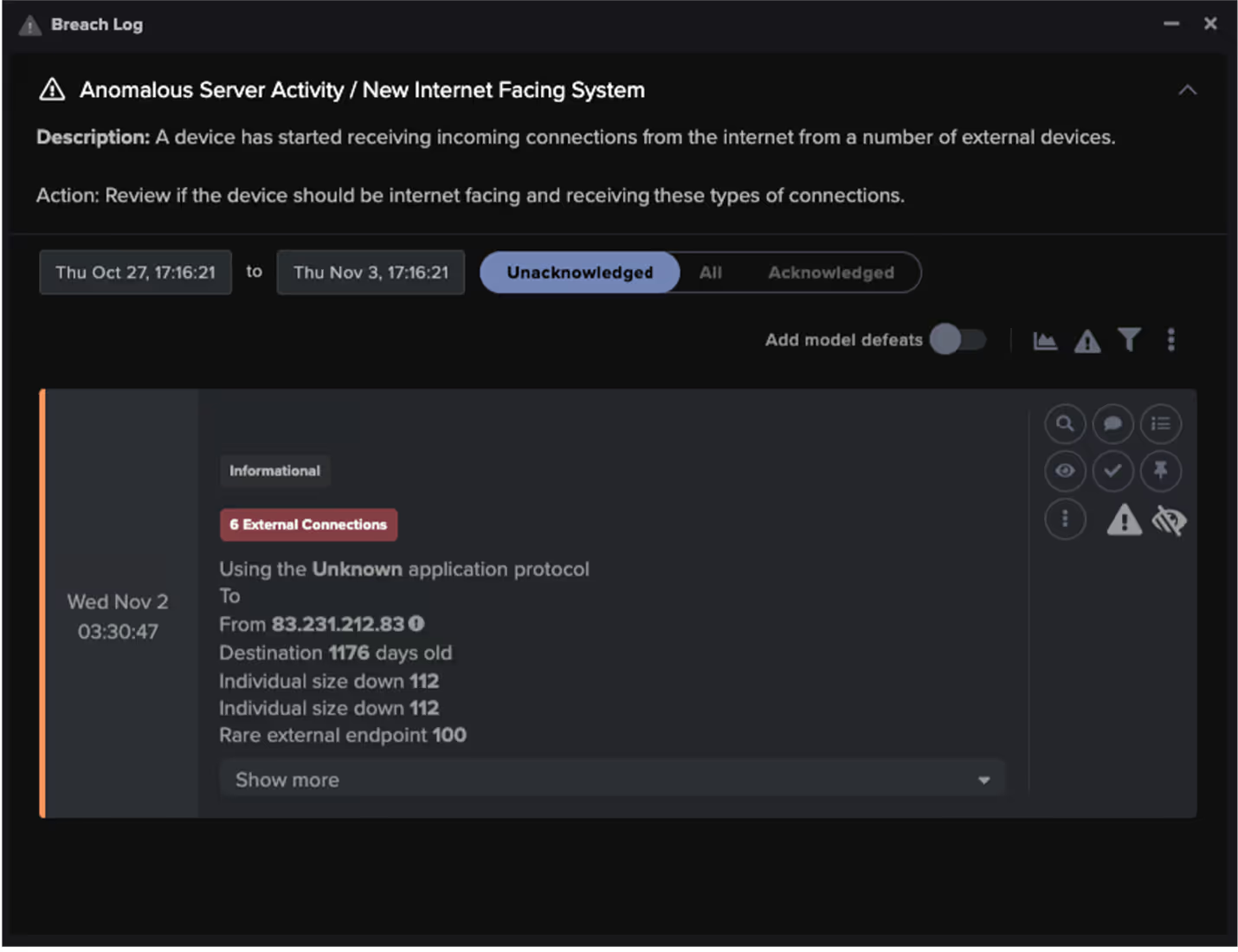

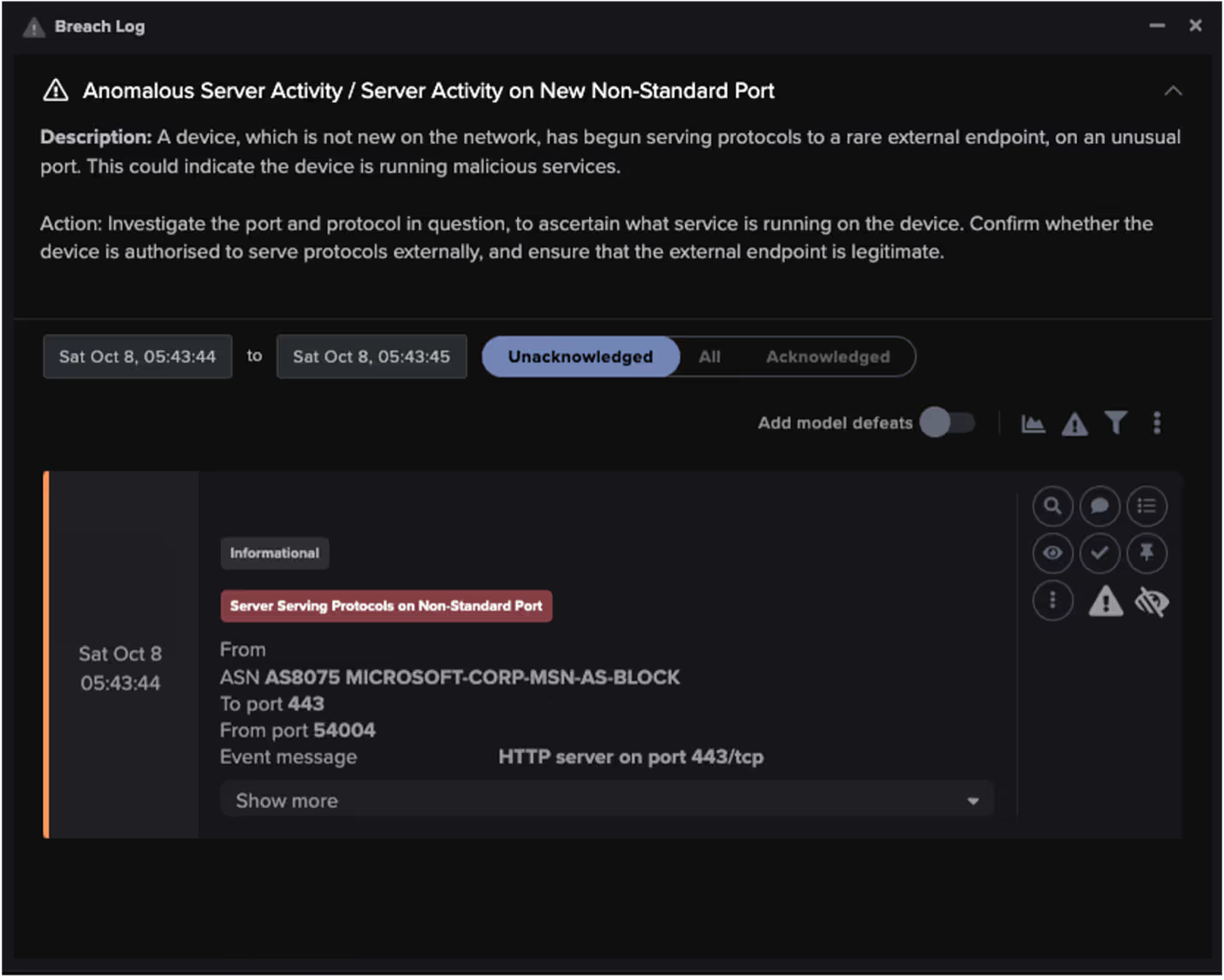

There are several models within Darktrace which monitor for risks against internet facing assets. For example, ‘Server A’ which had an open 3389 port on ASM registered the following model breach in the network:

A model like this could highlight a misconfiguration that has caused an internal device to become unexpectedly open to the internet. It could also suggest a compromised device that has now been opened to the internet to allow further exploitation. If the result of a sudden change, such an asset would also be detected by ASM and highlighted within the ‘New Assets’ part of the Insights page. Ultimately this connection was not malicious, however it shows the ability for security teams to track between PREVENT to DETECT and verify an initial compromise.

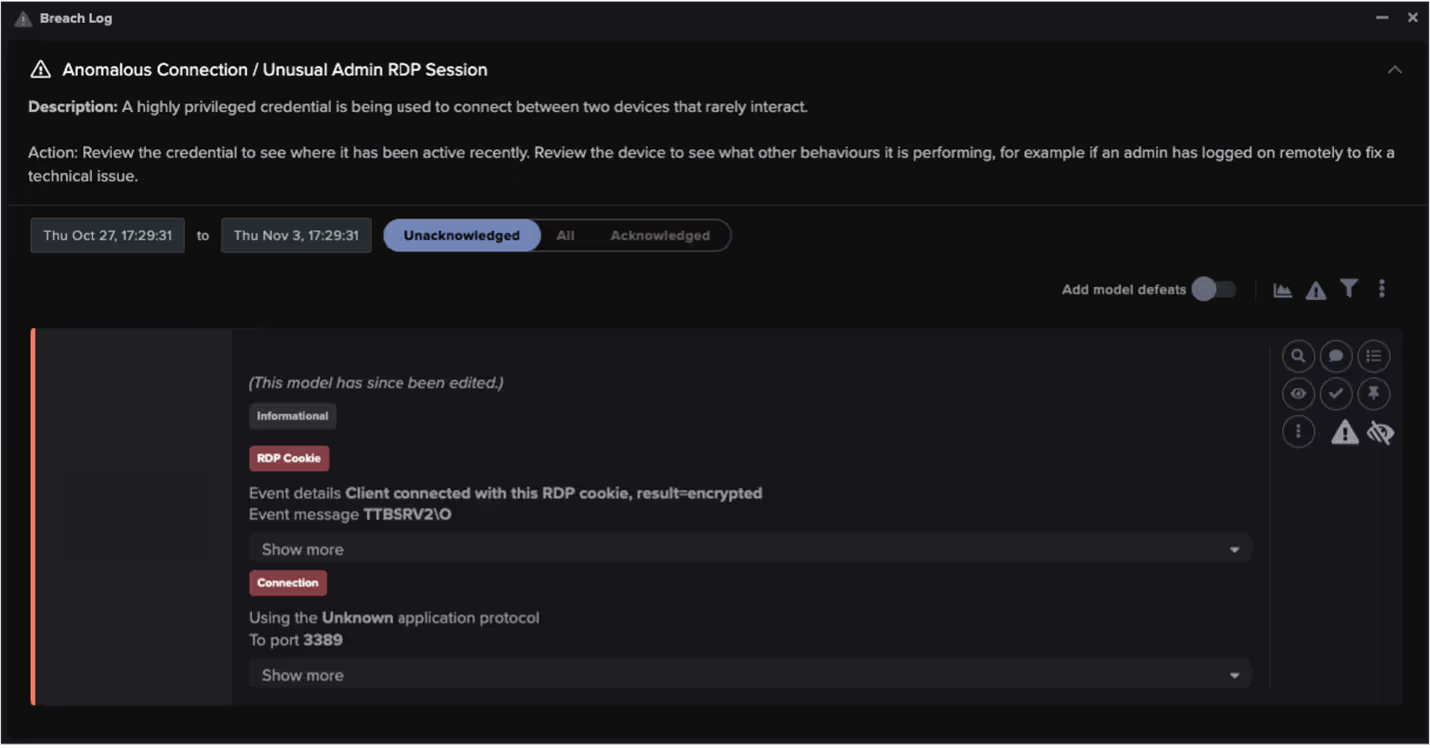

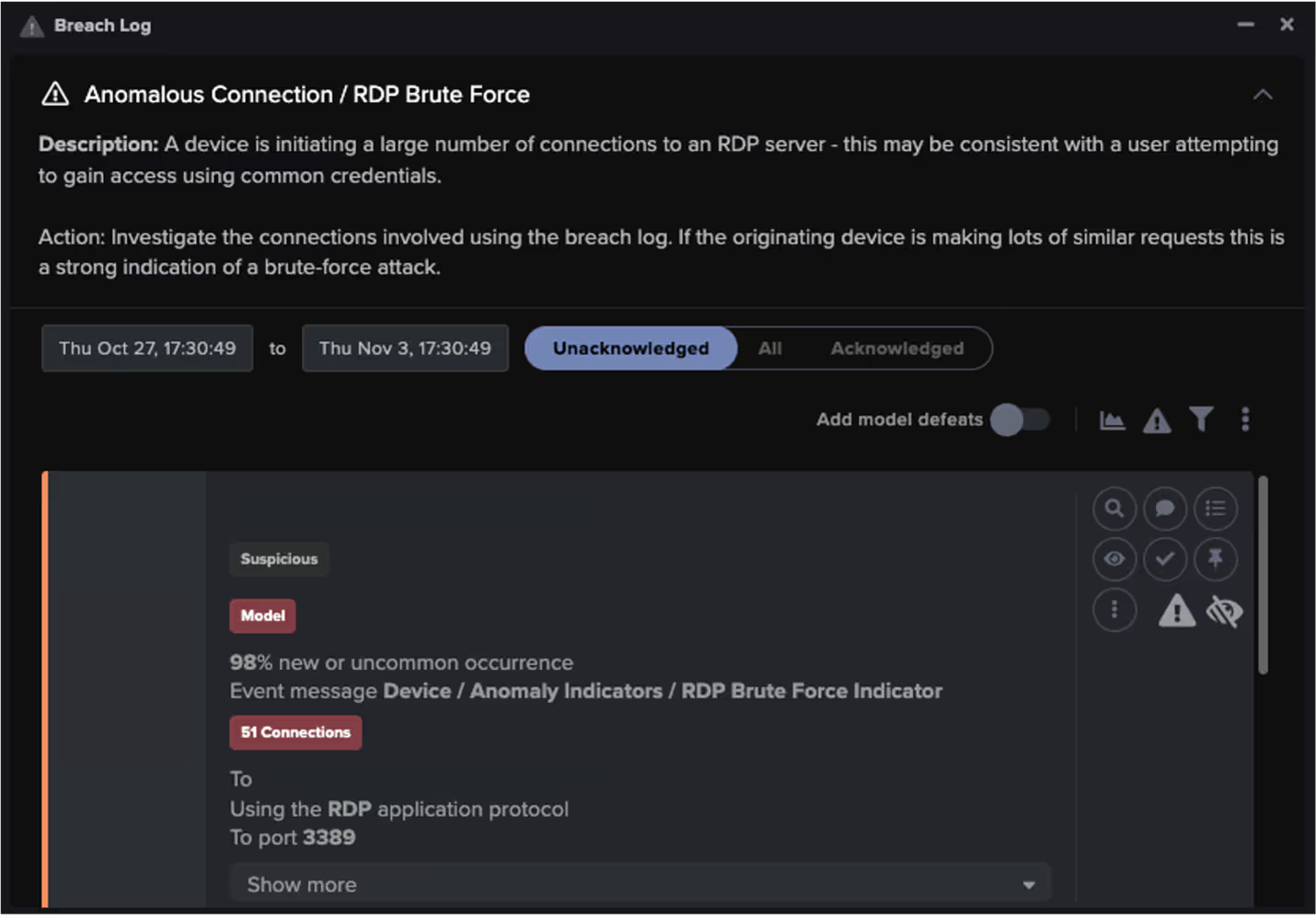

A mock scenario can take this further. Using the continued example of an open port 3389 intrusion, new RDP cookies may be registered (perhaps even administrative). This could enable further lateral movement and eventual privilege escalation. Various DETECT models would highlight actions of this nature, two examples are below:

Alongside efforts to move laterally, Darktrace may find attempts at reconnaissance or C2 communication from compromised internet facing devices by looking at Darktrace DETECT model breaches including ‘Network Scan’, ‘SMB Scanning’ and ‘Active Directory Reconnaissance’. In this case the network also saw repeated failed internal connections followed by the ‘LDAP Brute-Force Activity model’ around the same time as the RDP activity. Had this been malicious, DETECT would then continue to provide visibility into the C2 and eventual malware deployment stages.

With the combined visibility of both tools, Darktrace users have support for greater triage across the whole kill chain. For customers also using RESPOND, actions will be taken from the DETECT alerting to subsequently block malicious activity. In doing so, inputs will have fed across the whole Cyber AI Loop by having learnt from PREVENT, DETECT and RESPOND.

This feed from the Cyber AI Loop works both ways. In Figure 9, below, a DETECT model breach shows a customer alert from an internet facing device:

This breach took place because an established server suddenly started serving HTTP sessions on a port commonly used for HTTPS (secure) connections. This could be an indicator that a criminal may have gained control of the device and set it to listen on the given port and enable direct connection to the attacker’s machine or command and control server. This device can be viewed by an analyst in its Darktrace PREVENT version, where new metrics can be observed from a perspective outside of the network.

This page reports the associated risks that could be leveraged by malicious actors. In this case, the events are not correlated, but in the event of an attack, this backwards pivoting could help to pinpoint a weak link in the chain and show what allowed the attacker into the network. In doing so this supports the remediation and recovery process. More importantly though, it allows organizations to be proactive and take appropriate security measures required before it could ever be exploited.

Concluding Thoughts

The combination of Darktrace / Attack Surface Management with Darktrace / NETWORK provides wide and in-depth visibility over a company’s infrastructure. Through the Darktrace platform, this coverage is continually learning and updating based on inputs from both. ASM can show companies the potential weaknesses that a cybercriminal could take advantage of. In turn this allows them to prioritize patching, updating, and management of their internet facing assets. At the same time, Darktrace will show the anomalous behavior of any of these internet facing devices, enabling security teams or respond to stop an attack. Use of these tools by an analyst together is effective in gaining informed security data which can be fed back to IT management. Leveraging this allows normal company operations to be performed without the worry of cyber disruption.

Credit to: Emma Foulger, Senior Cyber Analyst at Darktrace

.avif)

![Pivoting off the previous event by filtering the timeline to events within the same window using timestamp: [“2026-02-18T09:09:00Z” TO “2026-02-18T09:12:00Z”].](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/69a8a18526ca3e653316a596_Screenshot%202026-03-04%20at%201.17.50%E2%80%AFPM.png)