Recently in the Darktrace Blog we’ve explored how the current working conditions have resulted in a huge surge in spoofing and impersonation attacks, where attackers masquerade either as trusted colleagues or familiar brands.

These types of email attacks continue to be a successful tactic for cyber-criminals. Forever responsive and adaptive, attackers are taking advantage of the disruption to everyday operations by impersonating credible suppliers to send in fake invoices and other fraudulent emails.

How AI caught a fake invoice attack

This blog explores a string of counterfeit invoices sent to dozens of employees at a cutting-edge technology company. With valuable IP and several research labs, the company is a prime target for organized and ambitious cyber-criminals seeking maximum financial reward for their campaigns. In this particular incident, the threat-actors convincingly impersonated QuickBooks, a leading provider of book-keeping and accounting software, and part of the Intuit group which includes other recognizable brands like TurboTax and Mint.

The spoofed emails contained an invoice notification that closely imitated a legitimate monthly invoice that the organization would expect to receive from QuickBooks. If successfully delivered to the inbox, these would have appeared to come from [email protected][.]com.

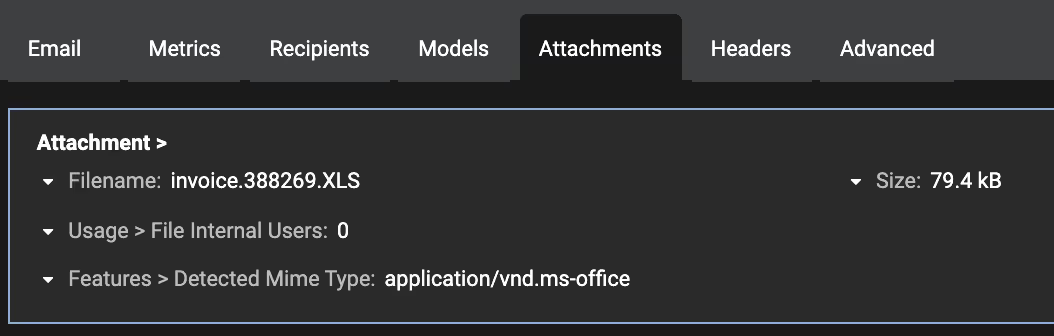

The ‘invoice’ attached to these emails was actually a macro-containing Office document.

The source of the spoofed emails was an IP address in Italy. Since this falls outside the range of IPs that are permitted by Intuit to send mail on their behalf, this breached the SPF model breach within Antigena Email.

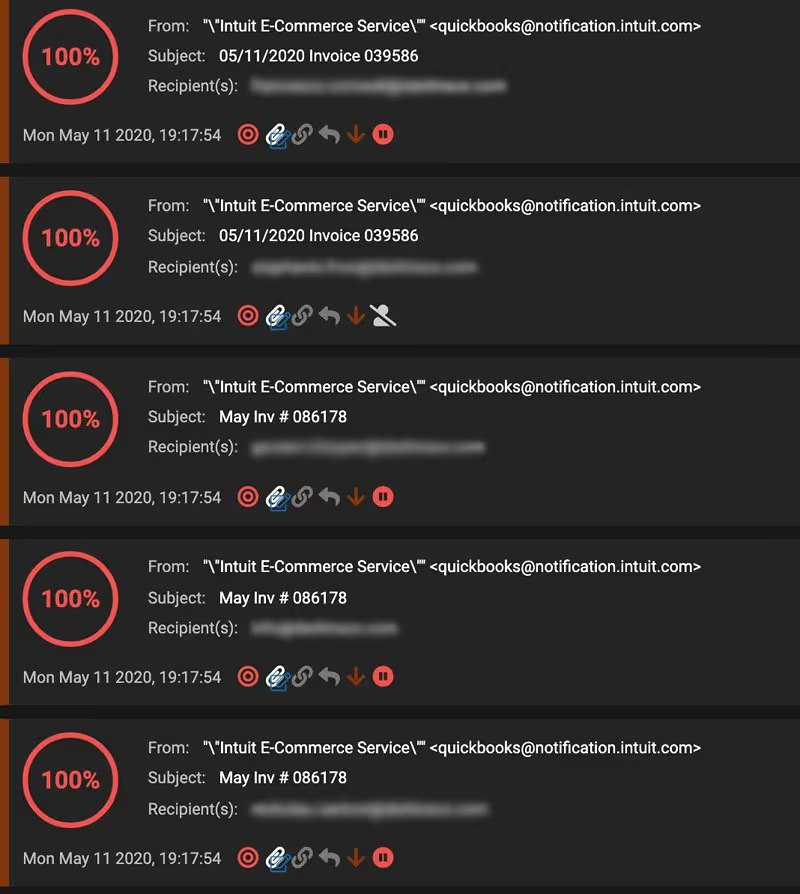

However, that in itself was not the main cause for Darktrace/Email’s detection – any mail server can run an SPF check. The primary factor behind the 100% anomaly score that Darktrace/Email assigned these emails was the high sender history of the email address – Darktrace was able to see that the failed SPF results were particularly suspicious against the background of SPF passes usually assigned to [email protected][.]com.

In addition, Darktrace/Email recognized that it would be highly unusual for this group of recipients, across multiple departments, to be receiving the same email from the same source – particularly of that particular subject matter. This caused the Cyber AI to hold the emails back in some cases, and in others it took the action to ‘unspoof’ the email, revealing that the invoice was not in fact from Quickbooks.

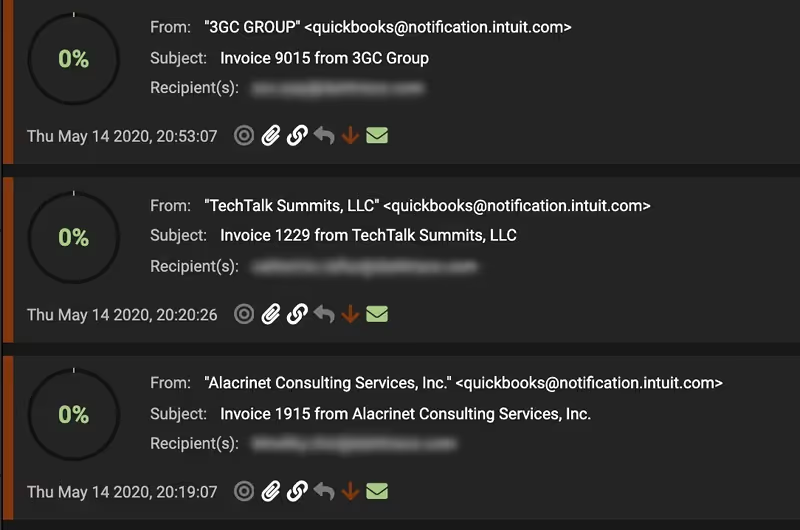

The above illustrates how these emails appeared in Darktrace’s Threat Visualizer, in comparison to normal legitimate invoices below. Note the identical sender address and similar style of subject line. Had Darktrace’s AI not been analyzing every inbound email in real time, these attacks would have been highly likely to succeed.

The below is a full list of the model breaches piled onto these emails, producing the overall anomaly score of 100% seen above.

Attachment/Dangerous AttachmentAttachment/SPF Anomalous AttachmentAttachment/Spoof Sender AttachmentAttachment/Unsolicited AttachmentSpoof/Meta Popular Domain SpoofType/High Sender HistoryUnusual/Behavioral AnomalyUnusual/Connection AnomaliesValidation/SPF AnomalousValidation/SPF Fail Known Correspondent

Catching the full range of email attacks

Thankfully, the organization in question was an early adopter of a Self-Learning, AI-powered approach to email security, and the attack was contained at an early stage. But this attack is nothing extraordinary – and these kind of impersonation attempts are affecting organizations across every industry on a daily basis.

The extension of the tax season in the US this year has brought with it a widened opportunity for cyber-criminals to exploit the flurry of activity with fake invoices and other similar attacks. Predictably, a second surge of attacks targeting individuals and small businesses has been reported.

We have already seen an increase of COVID-19 related email attacks. With attackers impersonating trusted brands like Intuit’s TurboTax and QuickBooks, the necessity for defenders to adopt Cyber AI as part of their email security defense is more prevalent than ever.