In the latter half of 2022, Darktrace observed a rise in Vidar Stealer infections across its client base. These infections consisted in a predictable series of network behaviors, including usage of certain social media platforms for the retrieval of Command and Control (C2) information and usage of certain URI patterns in C2 communications. In the blog post, we will provide details of the pattern of network activity observed in these Vidar Stealer infections, along with details of Darktrace’s coverage of the activity.

Background on Vidar Stealer

Vidar Stealer, first identified in 2018, is an info-stealer capable of obtaining and then exfiltrating sensitive data from users’ devices. This data includes banking details, saved passwords, IP addresses, browser history, login credentials, and crypto-wallet data [1]. The info-stealer, which is typically delivered via malicious spam emails, cracked software websites, malicious ads, and websites impersonating legitimate brands, is known to access profiles on social media platforms once it is running on a user’s device. The info-stealer does this to retrieve the IP address of its Command and Control (C2) server. After retrieving its main C2 address, the info-stealer, like many other info-stealers, is known to download several third-party Dynamic Link Libraries (DLLs) which it uses to gain access to sensitive data saved on the infected device. The info-stealer then bundles the sensitive data which it obtains and sends it back to the C2 server.

Details of Attack Chain

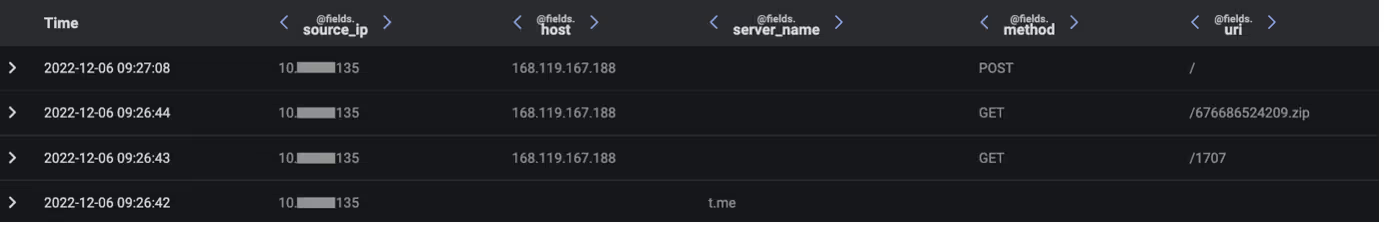

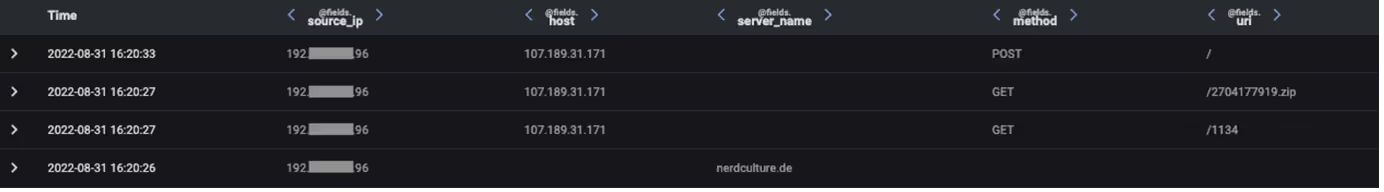

In the second half of 2022, Darktrace observed the following pattern of activity within many client networks:

1. User’s device makes an HTTPS connection to Telegram and/or to a Mastodon server

2. User’s device makes an HTTP GET request with an empty User-Agent header, an empty Host header and a target URI consisting of 4 digits to an unusual, external endpoint

3. User’s device makes an HTTP GET request with an empty User-Agent header, an empty Host header and a target URI consisting of 10 digits followed by ‘.zip’ to the unusual, external endpoint

4. User’s device makes an HTTP POST request with an empty User-Agent header, an empty Host header, and the target URI ‘/’ to the unusual, external endpoint

Each of these activity chains occurred as the result of a user running Vidar Stealer on their device. No common method was used to trick users into running Vidar Stealer on their devices. Rather, a variety of methods, ranging from malspam to cracked software downloads appear to have been used.

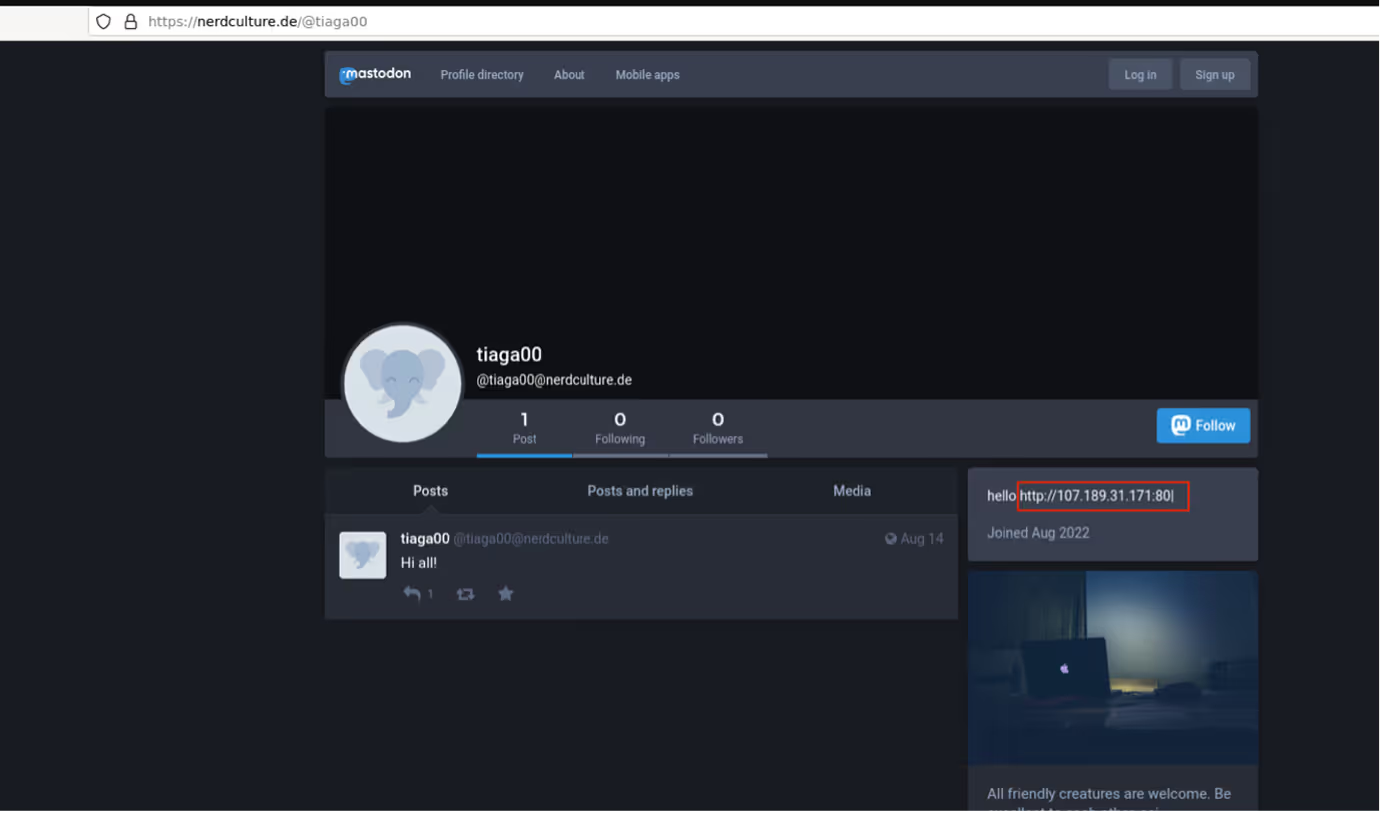

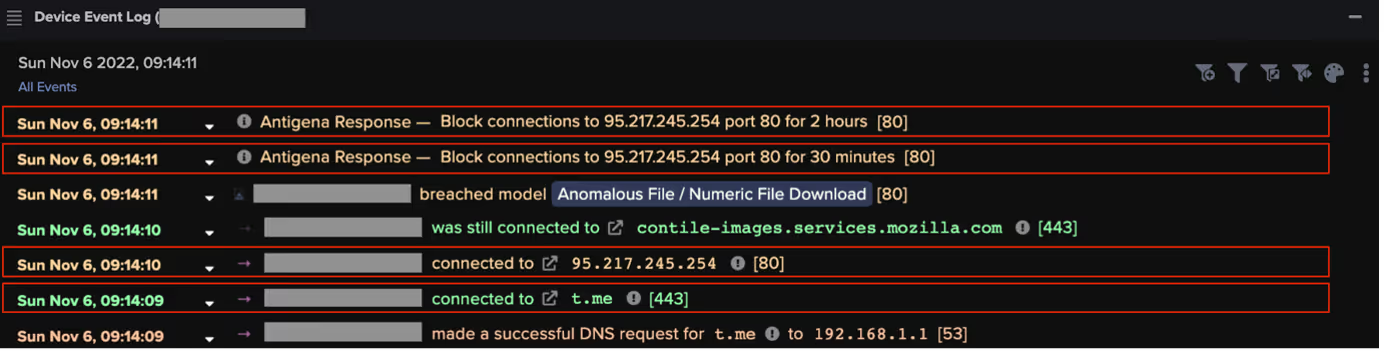

Once running on a user’s device, Vidar Stealer went on to make an HTTPS connection to either Telegram (https://t[.]me/) or a Mastodon server (https://nerdculture[.]de/ or https://ioc[.]exchange/). Telegram and Mastodon are social media platforms on which users can create profiles. Malicious actors are known to create profiles on these platforms and then to embed C2 information within the profiles’ descriptions [2]. In the Vidar cases observed across Darktrace’s client base, it seems that Vidar contacted Telegram and/or Mastodon servers in order to retrieve the IP address of its C2 server from a profile description. Since social media platforms are typically trusted, this ‘Dead Drop’ method of sharing C2 details with malware samples makes it possible for threat actors to regularly update C2 details without the communication of these changes being blocked.

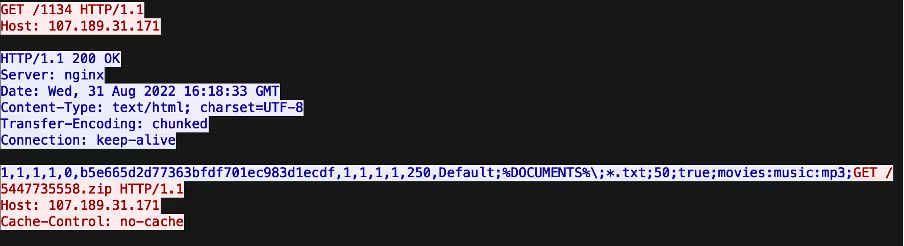

After retrieving its C2 address from the description of a Telegram or Mastodon profile, Vidar went on to make an HTTP GET request with an empty User-Agent header, an empty Host header and a target URI consisting of 4 digits to its C2 server. The sequences of digits appearing in these URIs are campaign IDs. The C2 server responded to Vidar’s GET request with configuration details that likely informed Vidar’s subsequent data stealing activities.

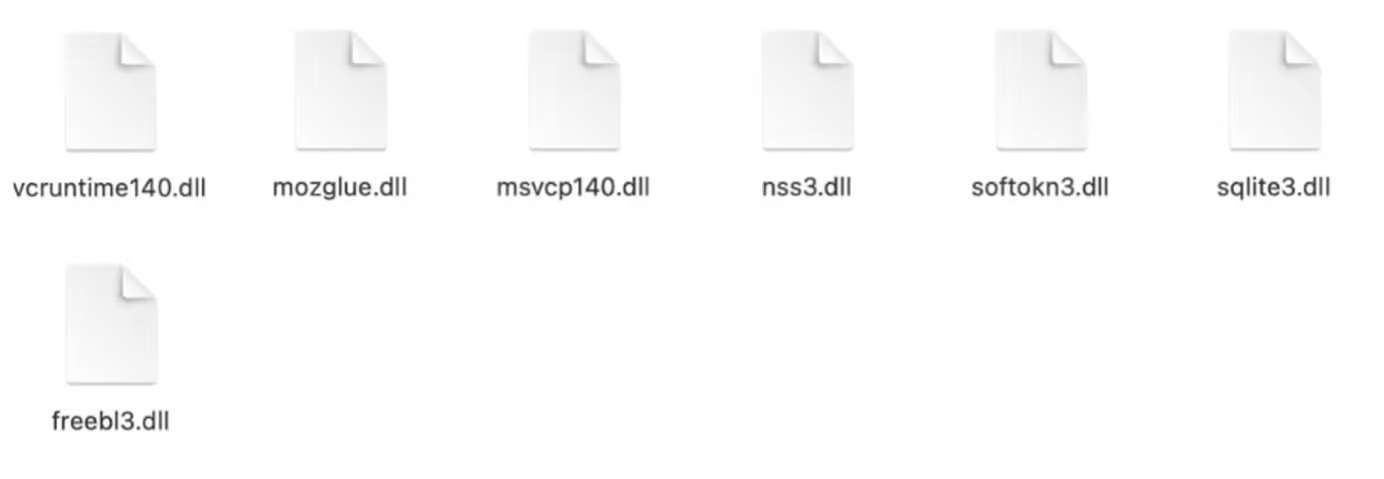

After receiving its configuration details, Vidar went on to make a GET request with an empty User-Agent header, an empty Host header and a target URI consisting of 10 digits followed by ‘.zip’ to the C2 server. This request was responded to with a ZIP file containing legitimate, third-party Dynamic Link Libraries such as ‘vcruntime140.dll’. Vidar used these libraries to gain access to sensitive data saved on the infected host.

After downloading a ZIP file containing third-party DLLs, Vidar made a POST request containing hundreds of kilobytes of data to the C2 endpoint. This POST request likely represented exfiltration of stolen information.

Darktrace Coverage

After infecting users’ devices, Vidar contacted either Telegram or Mastodon, and then made a series of HTTP requests to its C2 server. The info-stealer’s usage of social media platforms, along with its usage of ZIP files for tool transfer, complicate the detection of its activities. The info-stealer’s HTTP requests to its C2 server, however, caused the following Darktrace DETECT/Network models to breach:

- Anomalous File / Zip or Gzip from Rare External Location

- Anomalous File / Numeric File Download

- Anomalous Connection / Posting HTTP to IP Without Hostname

These model breaches did not occur due to users’ devices contacting IP addresses known to be associated with Vidar. In fact, at the time that the reported activities occurred, many of the contacted IP addresses had no OSINT associating them with Vidar activity. The cause of these model breaches was in fact the unusualness of the devices’ HTTP activities. When a Vidar-infected device was observed making HTTP requests to a C2 server, Darktrace recognised that this behavior was highly unusual both for the device and for other devices in the network. Darktrace’s recognition of this unusualness caused the model breaches to occur.

Vidar Stealer infections move incredibly fast, with the time between initial infection and data theft sometimes being less than a minute. In cases where Darktrace’s Autonomous Response technology was active, Darktrace RESPOND/Network was able to autonomously block Vidar’s connections to its C2 server immediately after the first connection was made.

Conclusion

In the latter half of 2022, a particular pattern of activity was prolific across Darktrace’s client base, with the pattern being seen in the networks of customers across a broad range of industry verticals and sizes. Further investigation revealed that this pattern of network activity was the result of Vidar Stealer infection. These infections moved fast and were effective at evading detection due to their usage of social media platforms for information retrieval and their usage of ZIP files for tool transfer. Since the impact of info-stealer activity typically occurs off-network, long after initial infection, insufficient detection of info-stealer activity leaves victims at risk of attackers operating unbeknownst to them and of powerful attack vectors being available to launch broad compromises.

Despite the evasion attempts made by the operators of Vidar, Darktrace DETECT/Network was able to detect the unusual HTTP activities which inevitably resulted from Vidar infections. When active, Darktrace RESPOND/Network was able to quickly take inhibitive actions against these unusual activities. Given the prevalence of Vidar Stealer [3] and the speed at which Vidar Stealer infections progress, Autonomous Response technology proves to be vital for protecting organizations from info-stealer activity.

Thanks to the Threat Research Team for its contributions to this blog.

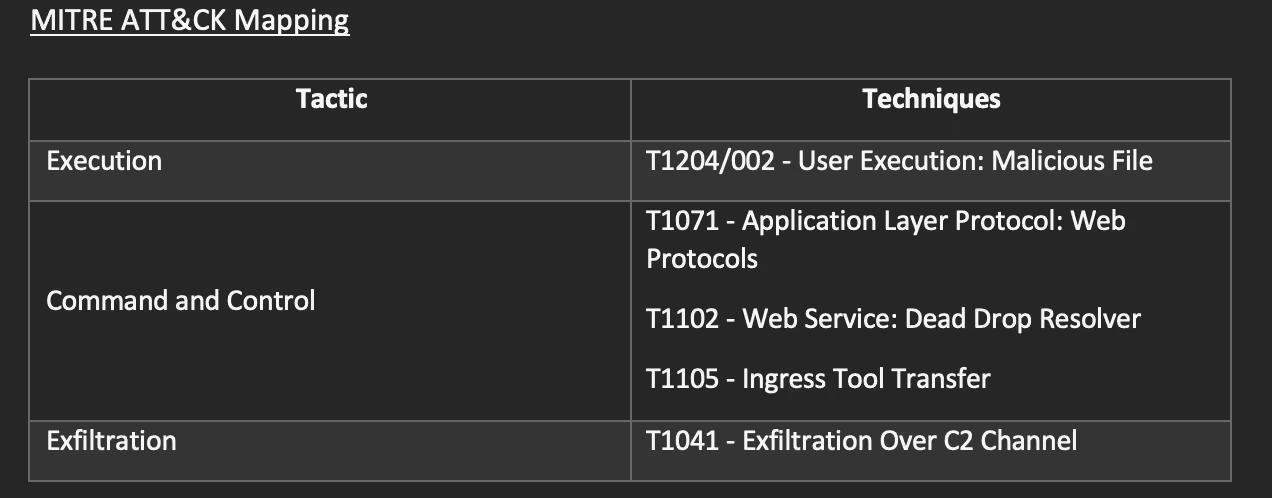

MITRE ATT&CK Mapping

List of IOCs

107.189.31[.]171 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

168.119.167[.]188 – Vidar C2 Endpoint

77.91.102[.]51 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

116.202.180[.]202 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

79.124.78[.]208 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

159.69.100[.]194 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

195.201.253[.]5 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

135.181.96[.]153 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

88.198.122[.]116 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

135.181.104[.]248 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

159.69.101[.]102 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

45.8.147[.]145 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

159.69.102[.]192 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

193.43.146[.]42 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

159.69.102[.]19 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

185.53.46[.]199 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

116.202.183[.]206 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

95.217.244[.]216 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

78.46.129[.]14 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

116.203.7[.]175 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

45.159.249[.]3 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

159.69.101[.]170 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

116.202.183[.]213 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

116.202.4[.]170 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

185.252.215[.]142 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

45.8.144[.]62 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

74.119.192[.]157 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

78.47.102[.]252 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

212.23.221[.]231 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

167.235.137[.]244 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

88.198.122[.]116 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

5.252.23[.]169 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

45.89.55[.]70 - Vidar C2 Endpoint

References

[1] https://blog.cyble.com/2021/10/26/vidar-stealer-under-the-lens-a-deep-dive-analysis/

[2] https://asec.ahnlab.com/en/44554/

[3] https://blog.sekoia.io/unveiling-of-a-large-resilient-infrastructure-distributing-information-stealers/