What is a QR Code?

Invented by a Japanese company in 1994 to label automobile parts, Quick Response codes, best known as QR codes, are rapidly becoming ubiquitous everywhere in the world. Their design, inspired by the board and black and white pieces of the game of Go, permits the storage of more information than regular barcodes and to access that information more quickly. The COVID-19 pandemic contributed to their increased popularity as it conveniently replaced physical media of all types for the purpose of content sharing. It is now common to see them in restaurant menus, plane tickets, advertisements and even in stickers containing minimal to no text pasted on lamp posts and other surfaces, enticing passers-by to scan its content.

QR Code Phishing Attacks (Quishing)

Recently, threat actors have been identified using QR codes too to embed malicious URLs leading the unsuspecting user to compromised websites containing malware or designed to harvest credentials. In the past month, Darktrace has observed an increase in the number of phishing emails leveraging malicious QR codes for malware distribution and/or credential harvesting, a new form of social engineering attack labelled “Quishing” (i.e., QR code phishing).

Between June 13 and June 22, 2023, Darktrace protected a tech company against one such Quishing attack when five of its senior employees were sent malicious emails impersonating the company’s IT department. The emails contained a QR code that led to a login page designed to harvest the credentials of these senior staff members. Fortunately for the customer, Darktrace / EMAIL thwarted this phishing campaign in the first instance and the emails never reached the employee inboxes.

Trends in Quishing Attacks

The Darktrace/Email team have noticed a recent and rapid increase in QR code abuse, suggesting that it is a growing tactic used by threat actors to deliver malicious payload links. This trend has also been observed by other security solutions [1] [2] [3] [4]. The Darktrace/Email team has identified malicious emails abusing QR codes in multiple ways. Examples include embedded image links which load a QR code and QR code images being delivered as attachments, such as those explored in this case study. Darktrace/Email is continually refining its detection of malicious QR codes and QR code extraction capabilities so that it can detect and block them regardless of their size and location within the email.

Quishing Attack Overview

The attack consisted of five emails, each sent from different sender and envelope addresses, displayed common points between them. The emails all conveyed a sense of urgency, either via the use of words such as “urgent”, “now”, “required” or “important” in the subject field or by marking the email as high priority, thus making the recipient believe the message is pressing and requires immediate attention.

Additionally, the subject of three of the emails directly referred to two factor authentication (2FA) enabling or QR code activation. Another particularity of these emails was that three of them attempted to impersonate the internal IT team of the company by inserting the company domain alongside strings, such as “it-desk” and “IT”, into the personal field of the emails. Email header fields like this are often abused by attackers to trick users by pretending to be an internal department or senior employee, thus avoiding more thorough validation checks. Both instilling a sense of urgency and including a known domain or name in the personal field are techniques that help draw attention to the email and maximize the chances that it is opened and engaged by the recipient.

However, threat actors also need to make sure that the emails actually reach the intended inboxes, and this can be done in several ways. In this case, several tactics were employed. Two of the five emails were sent from legitimate sender addresses that successfully passed SPF validation, suggesting they were sent from compromised accounts. SPF is a standard email authentication method that tells the receiving email servers whether emails have been sent from authorized servers for a given domain. Without SPF validation, emails are more likely to be categorized as spam and be sent to the junk folder as they do not come from authorized sources.

Another of the malicious emails, which also passed SPF checks, used a health care facility company domain in the header-from address field but was actually sent from a different domain (i.e., envelope domain), which lowers the value of the SPF authentication. However, the envelope domain observed in this instance belonged to a company recently acquired by the tech company targeted by the campaign.

This shows a high level of targeting from the attackers, who likely hoped that this detail would make the email more familiar and less suspicious. In another case, the sender domain (i.e., banes-gn[.]com) had been created just 6 days prior, thus lowering the chances of there being open-source intelligence (OSINT) available on the domain. This reduces the chances of the email being detected by traditional email security solutions relying on signatures and known-bad lists.

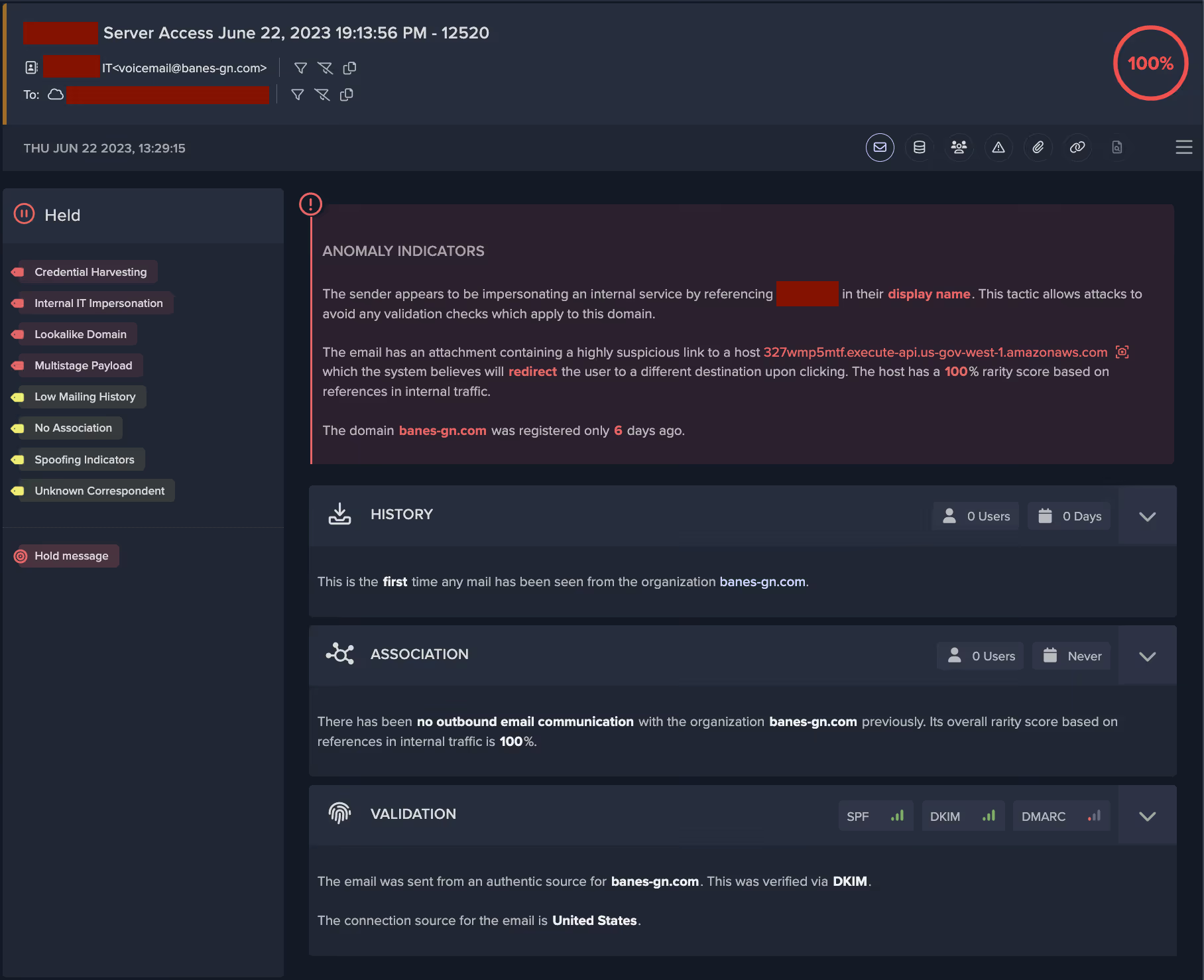

Darktrace Detects Quishing Attack

Despite its novelty, the domain was detected and assessed as highly suspicious by Darktrace. Darktrace/Email was able to recognize all of the emails as spoofing and impersonation attempts and applied the relevant tags to them, namely “IT Impersonation” and “Fake Account Alert”, depending on the choice of personal field and subject. The senders of the five emails had no prior history or association with the recipient nor the company as no previous correspondence had been observed between the sender and recipient. The tags applied informed on the likely intent and nature of the suspicious indicators present in the email, as shown in Figure 1.

Quishing Attack Tactics

Minimal Plain Text

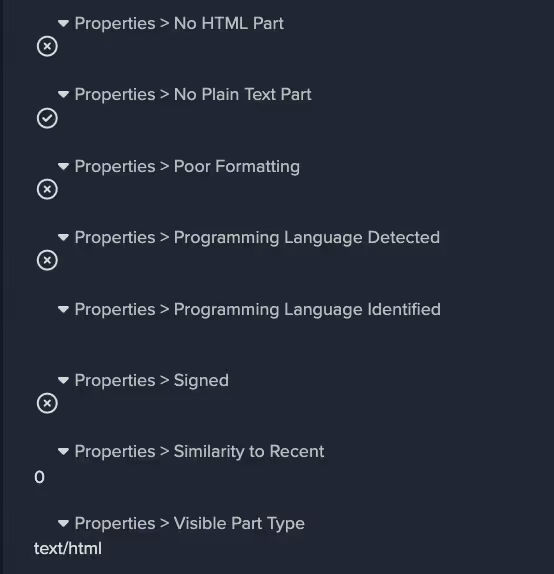

Another characteristic shared by these emails was that they had little to no text included in the body of the email and they did not contain a plain text portion, as shown in Figure 2. For most normal emails sent by email clients and most automated programs, an email will contain an HTML component and a text component, in addition to any potential attachments present. All the emails had one image attachment, suggesting the bulk of the message was displayed in the image rather than the email body. This hinders textual analysis and filtering of the email for suspicious keywords and language that could reveal its phishing intent. Additionally, the emails were well-formatted and used the logo of the well-known corporation Microsoft, suggesting some level of technical ability on the part of the attackers.

Attachment and link payloads

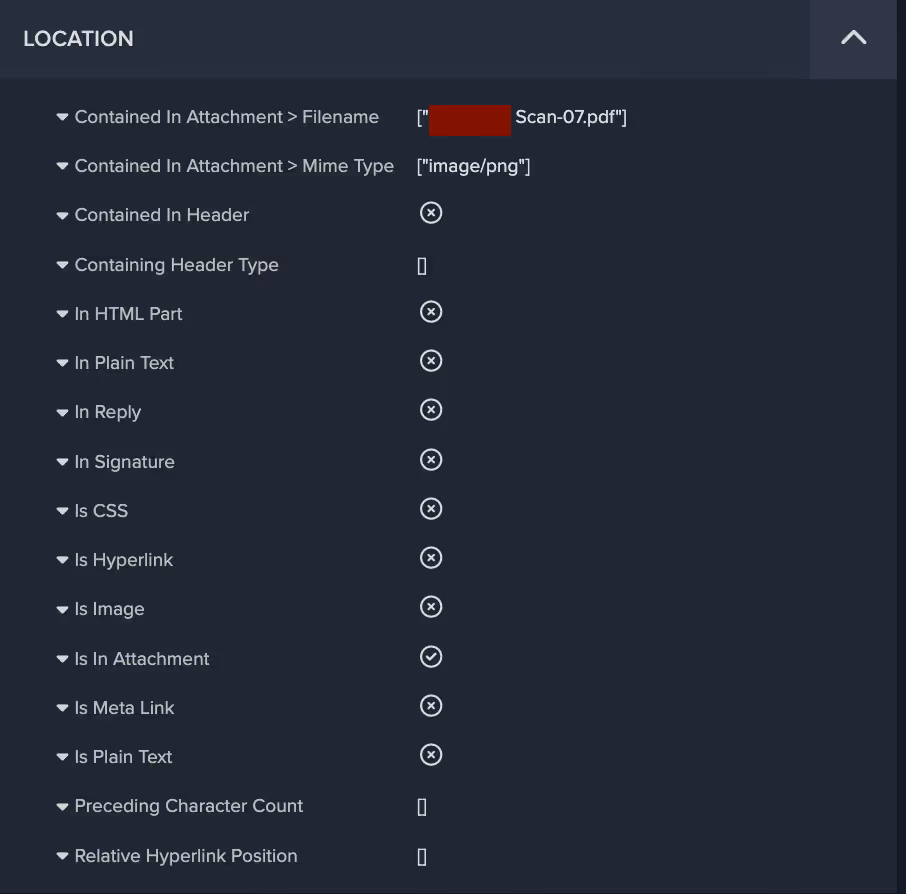

The threat actors employed some particularly innovative and novel techniques with regards to the attachments and link payloads within these emails. As previously stated, all emails contained an image attachment and one or two links. Figure 3 shows that Darktrace/Email detected that the malicious links present in these emails were located in the attachments, rather than the body of the email. This is a technique often employed by threat actors to bypass link analysis by security gateways. Darktrace/Email was also able to detect this link as a QR code link, as shown in Figure 4.

The majority of the text, as well as the malicious payload, was contained within the image attachment, which for one of the emails looked like this:

Convincing Appearance

As shown, the recipient is asked to setup 2FA authentication for their account within two days if they don’t want to be locked out. The visual formatting of the image, which includes a corporate logo and Privacy Statement and Acceptable Use Policy notices, is well balanced and convincing. The payload, in this case the QR code containing a malicious link, is positioned in the centre so as to draw attention and encourage the user to scan and click. This is a type of email employees are increasingly accustomed to receiving in order to log into corporate networks and applications. Therefore, recipients of such malicious emails might assume represents expected business activity and thus engage with the QR code without questioning it, especially if the email is claiming to be from the IT department.

Malicious Redirection

Two of the Quishing emails contained links to legitimate file storage and sharing solutions Amazon Web Services (AWS) and and InterPlanetary File System (IPFS), whose domains are less likely to be blocked by traditional security solutions. Additionally, the AWS domain link contained a redirect to a different domain that has been flagged as malicious by multiple security vendors [5]. Malicious redirection was observed in four of the five emails, initially from well-known and benign services’ domains such as bing[.]com and login[.]microsoftonline[.]com. This technique allows attackers to hide the real destination of the link from the user and increase the likelihood that the link is clicked. In two of the emails, the redirect domain had only recently been registered, and in one case, the redirect domain observed was hosted on the new .zip top level domain (i.e., docusafe[.]zip). The domain name suggests it is attempting to masquerade as a compressed file containing important documentation. As seen in Figure 6, a new Darktrace/Email feature allows customers to safely view the final destination of the link, which in this case was a seemingly fake Microsoft login page which could be used to harvest corporate credentials.

.avif)

Gathering Account Credentials

Given the nature of the landing page, it is highly likely that this phishing campaign had the objective of stealing the recipients’ credentials, as further indicated by the presence of the recipients’ email addresses in the links. Additionally, these emails were sent to senior employees, likely in an attempt to gather high value credentials to use in future attacks against the company. Had they succeeded, this would have represented a serious security incident, especially considering that 61% of attacks in 2023 involved stolen or hacked credentials according to Verizon’s 2023 data breach investigations report [6]. However, these emails received the highest possible anomaly score (100%) and were held by Darktrace/Email, thus ensuring that their intended recipients were never exposed to them.

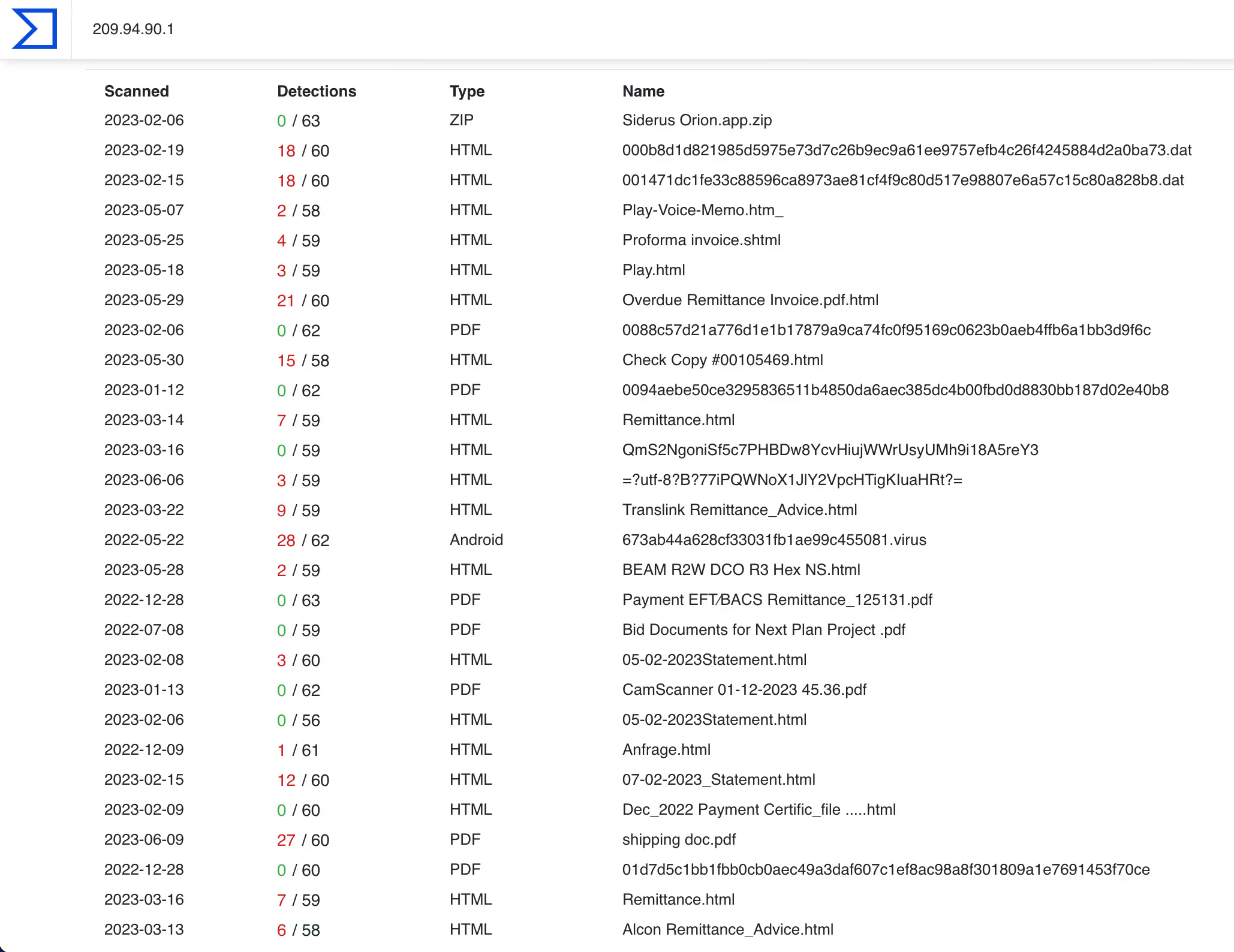

Looking at the indicators of compromise (IoCs) identified in this campaign, it appears that several of the IPs associated with the link payloads have been involved in previous phishing campaigns. Exploring the relations tab for these IPs in Virus Total, some of the communicating files appear to be .eml files and others have generic filenames including strings such as “invoice” “remittance details” “statement” “voice memo”, suggesting they have been involved in other phishing campaigns seemingly related to payment solicitation and other fraud attempts.

Conclusion

Even though the authors of this Quishing campaign used all the tricks in the book to ensure that their emails would arrive unactioned by security tools to the targeted high value recipients’ inboxes, Darktrace/Email was able to immediately recognize the phishing attempts for what they were and block the emails from reaching their destination.

This campaign used both classic and novel tactics, techniques, and procedures, but ultimately were detected and thwarted by Darktrace/Email. It is yet another example of the increasing attack sophistication mentioned in a previous Darktrace blog [7], wherein the attack landscape is moving from low-sophistication, low-impact, and generic phishing tactics to more targeted, sophisticated and higher impact attacks. Darktrace/Email does not rely on historical data nor known-bad lists and is best positioned to protect organizations from these highly targeted and sophisticated attacks.

References

[1] https://www.infosecurity-magazine.com/opinions/qr-codes-vulnerability-cybercrimes/

[2] https://www.helpnetsecurity.com/2023/03/21/qr-scan-scams/

[4] https://businessplus.ie/tech/qr-code-phishing-hp/

[5] https://www.virustotal.com/gui/domain/fistulacure.com

[6] https://www.verizon.com/business/en-gb/resources/reports/dbir/ ; https://www.verizon.com/business/en-gb/resources/reports/dbir/

[7] https://darktrace.com/blog/shifting-email-conversation

Darktrace Model Detections

Association models

No Sender or Content Association

New Sender

Unknown Sender

Low Sender Association

Link models

Focused Link to File Storage

Focused Rare Classified Links

New Unknown Hidden Redirect

High Risk Link + Low Sender Association

Watched Link Type

High Classified Link

File Storage From New

Hidden Link To File Storage

New Correspondent Classified Link

New Unknown Redirect

Rare Hidden Classified Link

Rare Hidden Link

Link To File Storage

Link To File Storage and Unknown Sender

Open Redirect

Unknown Sender Isolated Rare Link

Visually Prominent Link

Visually Prominent Link Unexpected For Sender

Low Link Association

Low Link Association and Unknown Sender

Spoof models

Fake Support Style

External Domain Similarities

Basic Known Entity Similarities

Unusual models

Urgent Request Banner

Urgent Request Banner + Basic Suspicious Sender

Very Young Header Domain

Young Header Domain

Unknown User Tracking

Unrelated Personal Name Address

Unrelated Personal Name Address + Freemail

Unusual Header TLD

Unusual Connection From Unknown

Unbroken Personal

Proximity models

Spam + Unknown Sender

Spam

Spam models

Unlikely Freemail Correspondence

Unlikely Freemail Personalization

General Indicators models

Incoming Mail Security Warning Message

Darktrace Model Tags

Credential Harvesting

Internal IT Impersonation

Multistage payload

Lookalike Domain

Phishing Link

Email Account Takeover

Fake Account Alert

Low Mailing History

No Association

Spoofing Indicators

Unknown Correspondent

VIP

Freemail

IoC - Type - Description & Confidence

fistulacure[.]com

domain

C2 Infrastructure

docusafe[.]zip

domain

Possible C2 Infrastructure

mwmailtec[.]com

domain

Possible C2 Infrastructure

czeromedia[.]com

domain

Possible C2 Infrastructure

192.40.165[.]109

IP address

Probable C2 Infrastructure

209.94.90[.]1

IP address

C2 Infrastructure

52.61.107[.]58

IP address

Possible C2 Infrastructure

40.126.32[.]133

IP address

Possible C2 Infrastructure

211.63.158[.]157

IP address

Possible C2 Infrastructure

119.9.27[.]129

IP address

Possible C2 Infrastructure

184.25.204[.]33

IP address

Possible C2 Infrastructure

40.107.8[.]107

IP address

Probable C2 Infrastructure

40.107.212[.]111

IP address

Possible Infrastructure

27.86.113[.]2

IP address

Possible C2 Infrastructure

192.40.191[.]19

IP address

Possible C2 Infrastructure

157.205.202[.]217

IP address

Possible C2 Infrastructure

a31f1f6063409ecebe8893e36d0048557142cbf13dbaf81af42bf14c43b12a48

SHA256 hash

Possible Malicious File

4c4fb35ab6445bf3749b9d0ab1b04f492f2bc651acb1bbf7af5f0a47502674c9

SHA256 hash

Possible Malicious File

f9c51d270091c34792b17391017a09724d9a7890737e00700dc36babeb97e252

SHA256 hash

Possible Malicious File

9f8ccfd616a8f73c69d25fd348b874d11a036b4d2b3fc7dbb99c1d6fa7413d9a

SHA256 hash

Possible Malicious File

b748894348c32d1dc5702085d70d846c6dd573296e79754df4857921e707c439

SHA256 hash

Possible Malicious File

.avif)

.avif)