With the continued rise of malware as a service (MaaS), it is now easier than ever to find and deploy information stealers [1]. Given this, it is crucial that companies begin to prioritize good cyber hygiene, and address compliance issues within their environments. Thanks to MaaS, attackers with little to no experience can amplify what might seem like a low-risk attack, into a significant compromise. This blog will investigate a compromise that could have been mitigated with better cyber hygiene and enhanced awareness around compliance issues.

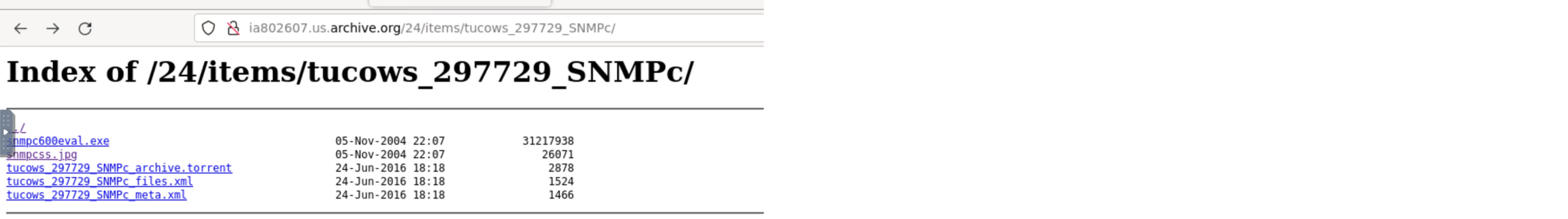

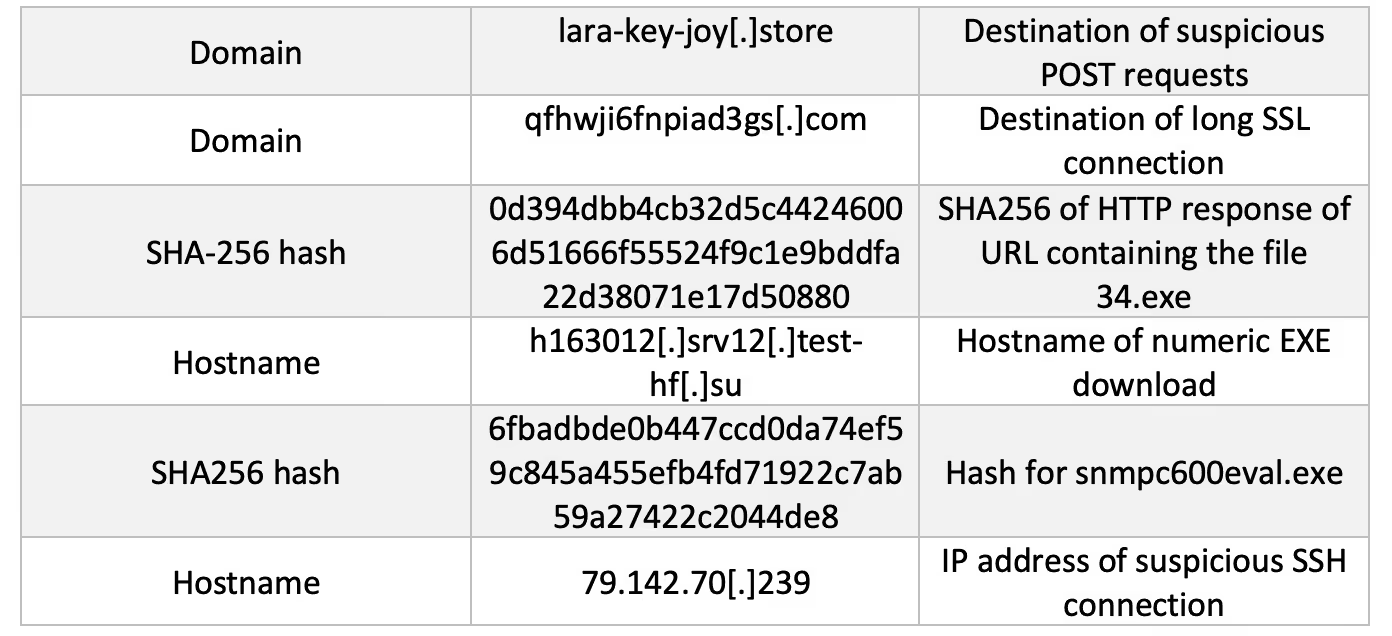

In May 2022 Darktrace DETECT/Network identified a device linked with multiple compliance alerts for ‘torrent’ activity within a Latin American telecommunications company. This culminated in the device downloading a suspicious executable file from an archived webpage. At first, analysis of the downloaded file indicated that it could be a legitimate, albeit outdated software relevant to the client’s industry vertical (SNMPc management tool for GeoDesy GD-300). However, as this was the first event before further suspicious activities, it was also possible that the software downloaded was packaged with malware and marked an initial compromise. Since early April, the device had regularly breached compliance alerts for both BitTorrent and uTorrent (a BitTorrent client). These connections occurred over a common torrenting port, 6881, and may have represented the infection vector.

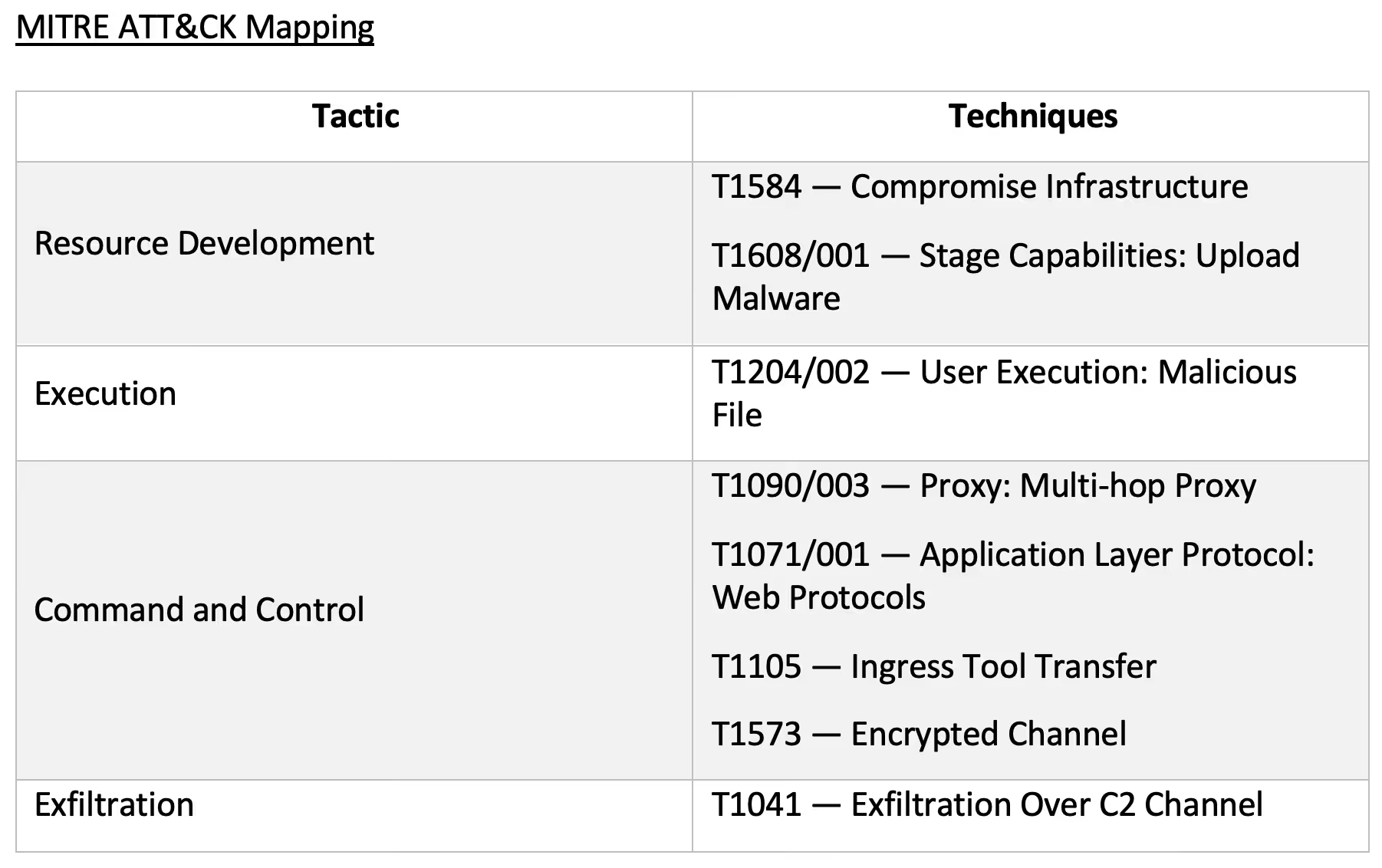

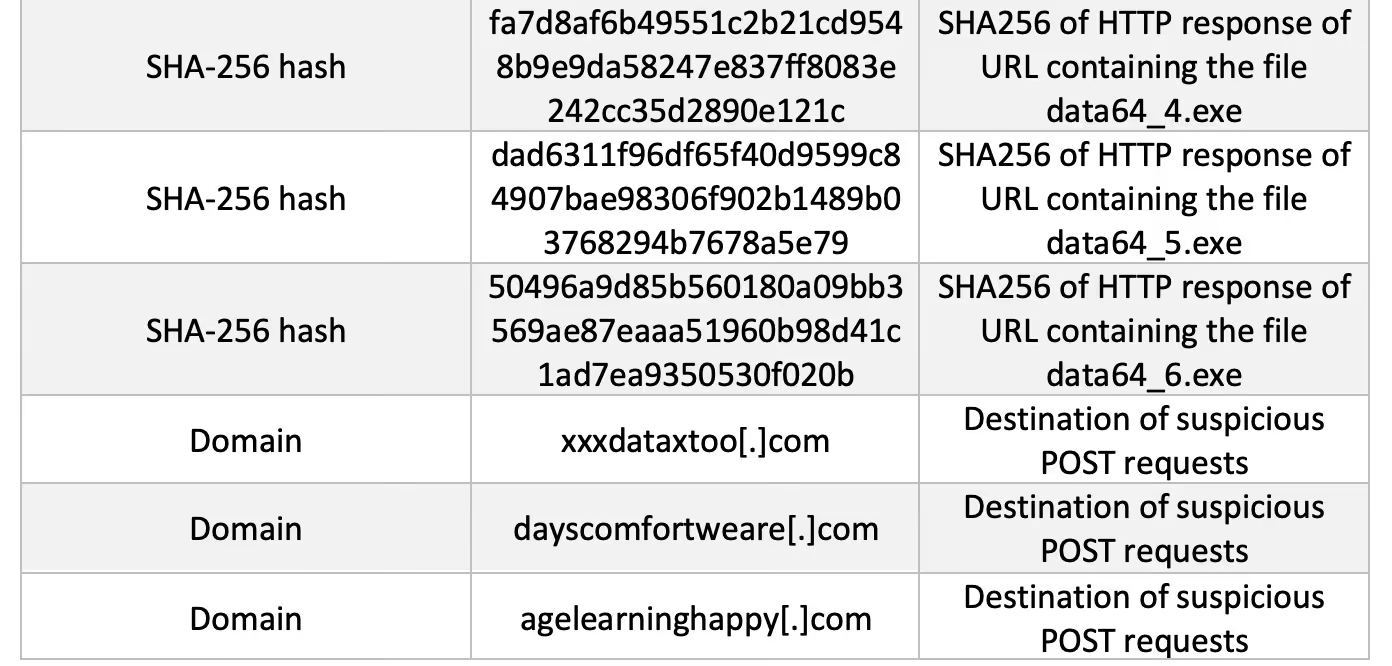

Shortly after the executable was downloaded, Darktrace DETECT alerted a new outbound SSH connection with the following notice in Advanced Search: ‘SSH::Heuristic_Login_Success’. This was highlighted because the breach device did not commonly make connections over this protocol and the destination was a never-before-seen Bulgarian IP address (79.142.70[.]239). The connection lasted 4 minutes, and the device downloaded 31.36 MB of data.

Following this, the breach device was seen making unusual HTTP connections to rare Russian and Danish endpoints using suspicious user agents. The Russian endpoint was noted for hosting a text file (‘incricinfo[.]com') that listed a single domain which was recently registered. The connections to the Danish endpoint were made to an IP with a URI that OSINT connected to the use of the BeamWinHTTP loader [2]. This loader can be used to download and execute other malware strains, in particular information stealers [3].

At the same time as the connections with the unusual user agents, the device was also seen downloading an executable file from the endpoint, ‘Yuuichirou-hanma[.]s3[.]pl-waw[.]scw[.]cloud’. Analysis of the file indicated that it may be used to deploy further malware and potentially unwanted programs (PUPs). BeamWinHTTP also causes installation of these PUPs which helps to load more nefarious programs and spread compromise.

This behavior was then seen as the device downloaded 5 different executable files from the endpoint, ‘hakhaulogistics[.]com’. This domain is linked to a Vietnamese logistics company that Darktrace had marked as new within the environment; it is possible that this domain was compromised and being used to host malicious infrastructure. At the point of compromise, several of the downloads were labeled as malicious by popular OSINT [4]. Additionally, at least one of the files was explicitly linked to the RedLine Information Stealer.

Shortly after, the device made connections to a known Tor relay node. Tor is commonly used as an avenue for C2 communication as it offers a way for attackers to anonymize and obfuscate their activity. It was at this point that the first Proactive Threat Notification (PTN) for this activity occurred. This ensured immediate follow-up investigation from Darktrace SOC and a timeline of events and impacted devices were issued to the customer’s security team directly.

By this point, Darktrace had identified a large volume of unusual outbound HTTP POSTs to a variety of endpoints that seemed to have no obvious function or service. Following these POST requests, the compromised device was seen initiating a long SSL connection to the domain, ‘www[.]qfhwji6fnpiad3gs[.]com’, which is likely to have be generated by an algorithm (DGA). Lastly, a little while after the SSL connections, the device was seen downloading another executable file from the Russian domain ‘test-hf[.]su’. Research on the file again suggested that it was associated with RedLine Stealer [5].

Dangers of Non-Compliance

Whilst the RedLine compromise was a matter of customer concern, the gap in their security was not visibility but rather best practice. It is important to note that prior to these events, the device was commonly seen sending and receiving connections associated with torrenting. In the past it has been observed that RedLine Stealer masquerades as ‘cracked’ software (software that has had its copy protection removed) [6]. In this instance, the initial download of the false ‘SNMPc’ executable may have been proof of this behavior.

This is a reminder that torrenting is also extremely popular as a peer-to-peer vector for transferring malicious files. Combined with the possibility of network throttling or unapproved VPN use, torrents are usually considered non-compliant within corporate settings. Whether the events here were kickstarted due to a user unwittingly downloading malicious software, or exposure to a malicious actor via BitTorrent use, both cases represent a user circumventing existing compliance controls or a lack of compliance control in general. It is important for organizations to make sure that their users are acting in ways that limit the company’s exposure to nefarious actors. Companies should routinely encourage proper cyber hygiene and implement access controls that block certain activities such as torrenting if threats like these are to be stopped in the future.

Regardless of what users are doing, Darktrace is positioned to detect and take action on compliance breaches and activity resulting from lack of compliance. The variety of C2 domains used in this blog incident were too quick for most security tools to alert on or for human teams to triage. However, this was no problem for Cyber AI analyst, which was able to draw together aspects of the attack across the kill chain and save a significant amount of time for both the customer security team and Darktrace SOC analysts. If active, Darktrace RESPOND could have blocked activities like the initial BitTorrent connections and incoming download, but with the right preventative measures, it wouldn’t have to. Darktrace PREVENT works continuously to harden defenses and preempt attackers, closing any vulnerabilities before they can be exploited. This includes performing attack surface management, attack path modelling, and security awareness training. In this case, Darktrace PREVENT could have highlighted torrenting activity as part of a potentially harmful attack path and recommended the best actions to mitigate it.

‘No Prior Experience required’

In the past, only highly skilled attackers could create and use the tools needed to attack organizations. With Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) proving highly profitable, however, it is no surprise that malware is also becoming a lucrative business. As SaaS can help legitimate companies with no development experience to use and maintain apps, MaaS can help attackers with little to no hacking experience compromise organizations and achieve their goals. RedLine Stealer is readily available, and not prohibitively expensive, meaning attacks can be carried out more frequently, and on a wider range of victims. The incident explored in this blog is proof of this, and a strong indication that security comes not only from strong visibility but also compliance and best practice too. With a powerful defensive tool like PREVENT, security teams can save time while feeling confident that they are keeping ahead of these aspects of security.

Thanks to Adam Stevens for his contributions to this blog.

Appendices

Darktrace Model Breaches

· Anomalous Connection / Multiple HTTP POSTs to Rare Hostname

· Anomalous Connection / New User Agent to IP Without Hostname

· Anomalous File / EXE from Rare External Location

· Anomalous File / Multiple EXE from Rare External

· Anomalous File / Numeric Exe Download

· Anomalous Server Activity / New User Agent from Internet Facing System

· Compliance / SSH to Rare External Destination

· Compromise / Anomalous File then Tor

· Compromise / Possible Tor Usage

· Device / Initial Breach Chain Compromise

· Device / Long Agent Connection to New Endpoint

References

[1] https://blog.sonicwall.com/en-us/2021/12/the-rise-and-growth-of-malware-as-a-service/

[2] https://asec.ahnlab.com/en/33679/

[3] https://asec.ahnlab.com/en/20930/

[4] https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/acfc06b4bcda03ecf4f9dc9b27c510b58ae3a6a9baf1ee821fc624467944467b & https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/dad6311f96df65f40d9599c84907bae98306f902b1489b03768294b7678a5e79

[5] https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/ff7574f9f1d15594e409bee206f5db6c76db7c90dda2ae4f241b77cd0c7b6bf6

.jpg)

%5B2%5D%20copy.avif)