Executive summary

- In the past few weeks, Darktrace has observed an increase in attacks against internet-facing systems, such as RDP. The initial intrusions usually take place via existing vulnerabilities or stolen, legitimate credentials. The Dharma ransomware attack described in this blog post is one such example.

- Old threats can be damaging – Dharma and its variants have been around for four years. This is a classic example of ‘legacy’ ransomware morphing and adapting to bypass traditional defenses.

- The intrusion shows signs that indicate the threat-actors are aware of – and are actively exploiting – the COVID-19 situation.

- In the current threat landscape surrounding COVID-19, Darktrace recommends monitoring internet-facing systems and critical servers closely – keeping track of administrative credentials and carefully considering security when rapidly deploying internet-facing infrastructure.

Introduction

In mid-April, Darktrace detected a targeted Dharma ransomware attack on a UK company. The initial point of intrusion was via RDP – this represents a very common attack method of infection that Darktrace has observed in the broader threat landscape over the past few weeks.

This blog post highlights every stage of the attack lifecycle and details the attacker’s techniques, tools and procedures (TTP) – all detected by Darktrace.

Dharma – a varient of the CrySIS malware family – first appeared in 2016 and uses multiple intrusion vectors. It distributes its malware as an attachment in a spam email, by disguising it as an installation file for legitimate software, or by exploiting an open RDP connection through internet-facing servers. When Dharma has finished encrypting files, it drops a ransom note with the contact email address in the encrypted SMB files.

Darktrace had strong, real-time detections of the attack – however the absence of eyes on the user interface prior to the encryption activity, and without Autonomous Response deployed in Active Mode, these alerts were only actioned after the ransomware was unleashed. Fortunately, it was unable to spread within the organization, thanks to human intervention at the peak of the attack. However, Darktrace Antigena in active mode would have significantly slowed down the attack.

Timeline

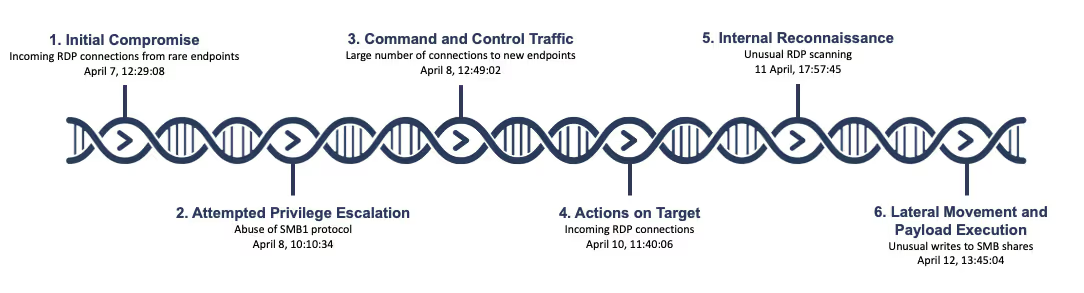

The timeline below provides a rough overview of the major attack phases over five days of activity.

Figure 1: A timeline of the attack

Technical analysis

Darktrace detected that the main device hit by the attack was an internet-facing RDP server (‘RDP server’). Dharma used network-level encryption here: the ransomware activity takes place over the network protocol SMB.

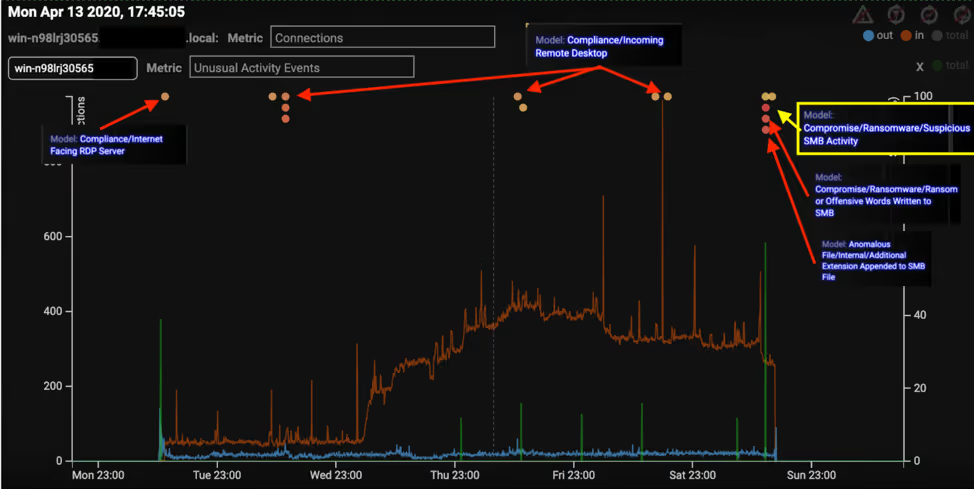

Below is a chronological overview of all Darktrace detections that fired during this attack: Darktrace detected and reported every single unusual or suspicious event occurring on the RDP server.

Figure 2: An overview of Darktrace detections

Initial compromise

On April 7, the RDP server began receiving a large number of incoming connections from rare IP addresses on the internet.

On April 7, the RDP server began receiving a large number of incoming connections from rare IP addresses on the internet. This means a lot of IP addresses on the internet that usually don’t connect to this company started connection attempts over RDP. The top five cookies used to authenticate show that the source IPs were located in Russia, the Netherlands, Korea, the United States, and Germany.

It is highly likely that the RDP credential used in this attack had been compromised prior to the attack – either via common brute-force methods, credential stuffing attacks, or phishing. Indeed, a TTP growing in popularity is to buy RDP credentials on marketplaces and skip to initial access.

Attempted privilege escalation

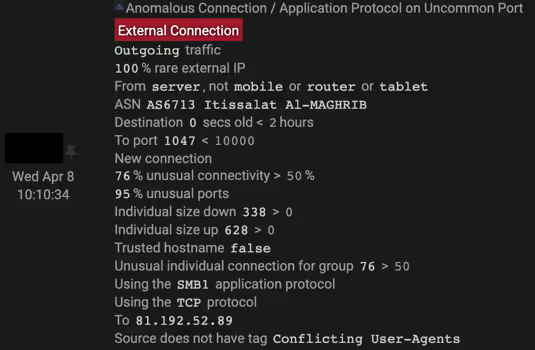

The following day, the malicious actor abused the SMB version 1 protocol, notorious for always-on null sessions which offer unauthenticated users’ information about the machine – such as password policies, usernames, group names, machine names, user and host SIDs. What followed was very unusual: the server connected externally to a rare IP address located in Morocco.

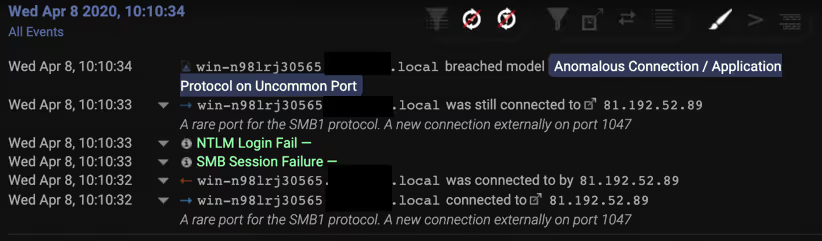

Next, the attacker attempted a failed SMB session to the external IP over an unusual port. Darktrace detected this activity as highly anomalous, as it had previously learned that SMB is usually not used in this fashion within this organization – and certainly not for external communication over this port.

Figure 3: Darktrace detecting the rare external IP address

Figure 4: The SMB session failure and the rare connection over port 1047

Command and control traffic

As the entire attack occurred over five days, this aligns with a smash-and-grab approach, rather than a highly covert, low-and-slow operation.

Two hours later, the server initiated a large number of anomalous and rare connections to external destinations located in India, China, and Italy – amongst other destinations the server had never communicated with before. The attacker was now attempting to establish persistence and create stronger channels for command and control (C2). As the entire attack occurred over five days, this aligns with a smash-and-grab approach, rather than a highly covert, low-and-slow operation.

Actions on target

Notwithstanding this approach, the malicious actor remained dormant for two days, biding their time until April 10 — a public holiday in the UK — when security teams would be notably less responsive. This pause in activity provides supporting evidence that the attack was human-driven.

Figure 5: The unusual RDP connections detected by Darktrace

The RDP server then began receiving incoming remote desktop connections from 100% rare IP addresses located in the Netherlands, Latvia, and Poland.

Internal reconnaissance

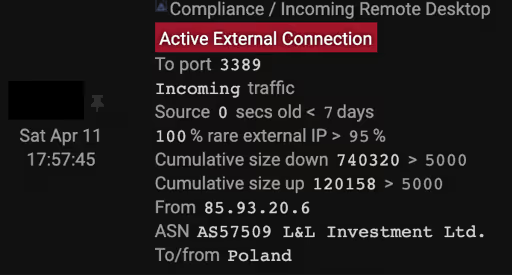

The IP address 85.93.20[.]6, hosted at the time of investigation in Panama, made two connections to the server, using an administrative credential. On April 12, as other inbound RDP connections scanned the network, the volume of data transferred by the RDP server to this IP address spiked. The RDP server never scans the internal network. Darktrace identified this as highly unusual activity.

Figure 6: Darktrace detects the anomalous external data transfer

Lateral movement and payload execution

Finally, on April 12, the attackers executed the Dharma payload at 13:45. The RDP server wrote a number of files over the SMB protocol, appended with a file extension containing a throwaway email account possibly evoking the current COVID-19 pandemic, ‘cov2020@aol[.]com’. The use of string ‘…@aol.com].ROGER’ and presence of a file named ‘FILES ENCRYPTED.txt’ resembles previous Dharma compromises.

Parallel to the encryption activity, the ransomware tried to spread and infect other machines by initiating successful SMB authentications using the same administrator credential seen during the internal reconnaissance. However, the destination devices did not encrypt any files themselves.

It was during the encryption activity that the internal IT staff pulled the plug from the compromised RDP server, thus ending the ransomware activity.

Conclusion

This incident supports the idea that ‘legacy’ ransomware may morph to resurrect itself to exploit vulnerabilities in remote working infrastructure during this pandemic.

Dharma executed here a fast-acting, planned, targeted, ransomware attack. The attackers used off-the-shelf tools (RDP, abusing SMB1 protocol) blurring detection and attribution by blending in with typical administrator activity.

Darktrace detected every stage of the attack without having to depend on threat intelligence or rules and signatures, and the internal security team acted on the malicious activity to prevent further damage.

This incident supports the idea that ‘legacy’ ransomware may morph to resurrect itself to exploit vulnerabilities in remote working infrastructure during this pandemic. Poorly-secured public-facing systems have been rushed out and security is neglected as companies prioritize availability – sacrificing security in the process. Financially-motivated actors weaponize these weak points.

The use of the COVID-related email ‘cov2020@aol[.]com’ during the attack indicates that the threat-actor is aware of and abusing the current global pandemic.

Recent attacks, such as APT41’s exploitation of the Zoho Manage Engine vulnerability last March, show that attacks against internet-facing infrastructure are gaining popularity as the initial intrusion vector. Indeed, as many as 85% of ransomware attacks use RDP as an entry vector. Ensuring that backups are isolated, configurations are hardened, and systems are patched is not enough – real-time detection of every anomalous action can help protect potential victims of ransomware.

Technical Details

Some of the detections on the RDP server:

- Compliance / Internet Facing RDP server – exposure of critical server to Internet

- Anomalous Connection / Application Protocol on Uncommon Port – external connections using an unusual port to rare endpoints

- Device / Large Number of Connections to New Endpoints – indicative of peer-to-peer or scanning activity

- Compliance / Incoming Remote Desktop – device is remotely controlled from an external source, increased rick of bruteforce

- Compromise / Ransomware / Suspicious SMB Activity – reading and writing similar volumes of data to remote file shares, indicative of files being overwritten and encrypted

- Anomalous File / Internal / Additional Extension Appended to SMB File – device is renaming network share files with an added extension, seen during ransomware activity

The graph below shows the timeline of Darktrace detections on the RDP server. The attack lifecycle is clearly observable.

Figure 7: The model breaches occurring over time