Introduction

Throughout April 2022, Darktrace observed several cases in which threat actors used the loader known as ‘BumbleBee’ to install Cobalt Strike Beacon onto victim systems. The threat actors then leveraged Cobalt Strike Beacon to conduct network reconnaissance, obtain account password data, and write malicious payloads across the network. In this article, we will provide details of the actions threat actors took during their intrusions, as well as details of the network-based behaviours which served as evidence of the actors’ activities.

BumbleBee

In March 2022, Google’s Threat Analysis Group (TAG) provided details of the activities of an Initial Access Broker (IAB) group dubbed ‘Exotic Lily’ [1]. Before March 2022, Google’s TAG observed Exotic Lily leveraging sophisticated impersonation techniques to trick employees of targeted organisations into downloading ISO disc image files from legitimate file storage services such as WeTransfer. These ISO files contained a Windows shortcut LNK file and a BazarLoader Dynamic Link Library (i.e, DLL). BazarLoader is a member of the Bazar family — a family of malware (including both BazarLoader and BazarBackdoor) with strong ties to the Trickbot malware, the Anchor malware family, and Conti ransomware. BazarLoader, which is typically distributed via email campaigns or via fraudulent call campaigns, has been known to drop Cobalt Strike as a precursor to Conti ransomware deployment [2].

In March 2022, Google’s TAG observed Exotic Lily leveraging file storage services to distribute an ISO file containing a DLL which, when executed, caused the victim machine to make HTTP requests with the user-agent string ‘bumblebee’. Google’s TAG consequently called this DLL payload ‘BumbleBee’. Since Google’s discovery of BumbleBee back in March, several threat research teams have reported BumbleBee samples dropping Cobalt Strike [1]/[3]/[4]/[5]. It has also been reported by Proofpoint [3] that other threat actors such as TA578 and TA579 transitioned to BumbleBee in March 2022.

Interestingly, BazarLoader’s replacement with BumbleBee seems to coincide with the leaking of the Conti ransomware gang’s Jabber chat logs at the end of February 2022. On February 25th, 2022, the Conti gang published a blog post announcing their full support for the Russian state’s invasion of Ukraine [6].

Within days of sharing their support for Russia, logs from a server hosting the group’s Jabber communications began to be leaked on Twitter by @ContiLeaks [7]. The leaked logs included records of conversations among nearly 500 threat actors between Jan 2020 and March 2022 [8]. The Jabber logs were supposedly stolen and leaked by a Ukrainian security researcher [3]/[6].

Affiliates of the Conti ransomware group were known to use BazarLoader to deliver Conti ransomware [9]. BumbleBee has now also been linked to the Conti ransomware group by several threat research teams [1]/[10]/[11]. The fact that threat actors’ transition from BazarLoader to BumbleBee coincides with the leak of Conti’s Jabber chat logs may indicate that the transition occurred as a result of the leaks [3]. Since the transition, BumbleBee has become a significant tool in the cyber-crime ecosystem, with links to several ransomware operations such as Conti, Quantum, and Mountlocker [11]. The rising use of BumbleBee by threat actors, and particularly ransomware actors, makes the early detection of BumbleBee key to identifying the preparatory stages of ransomware attacks.

Intrusion Kill Chain

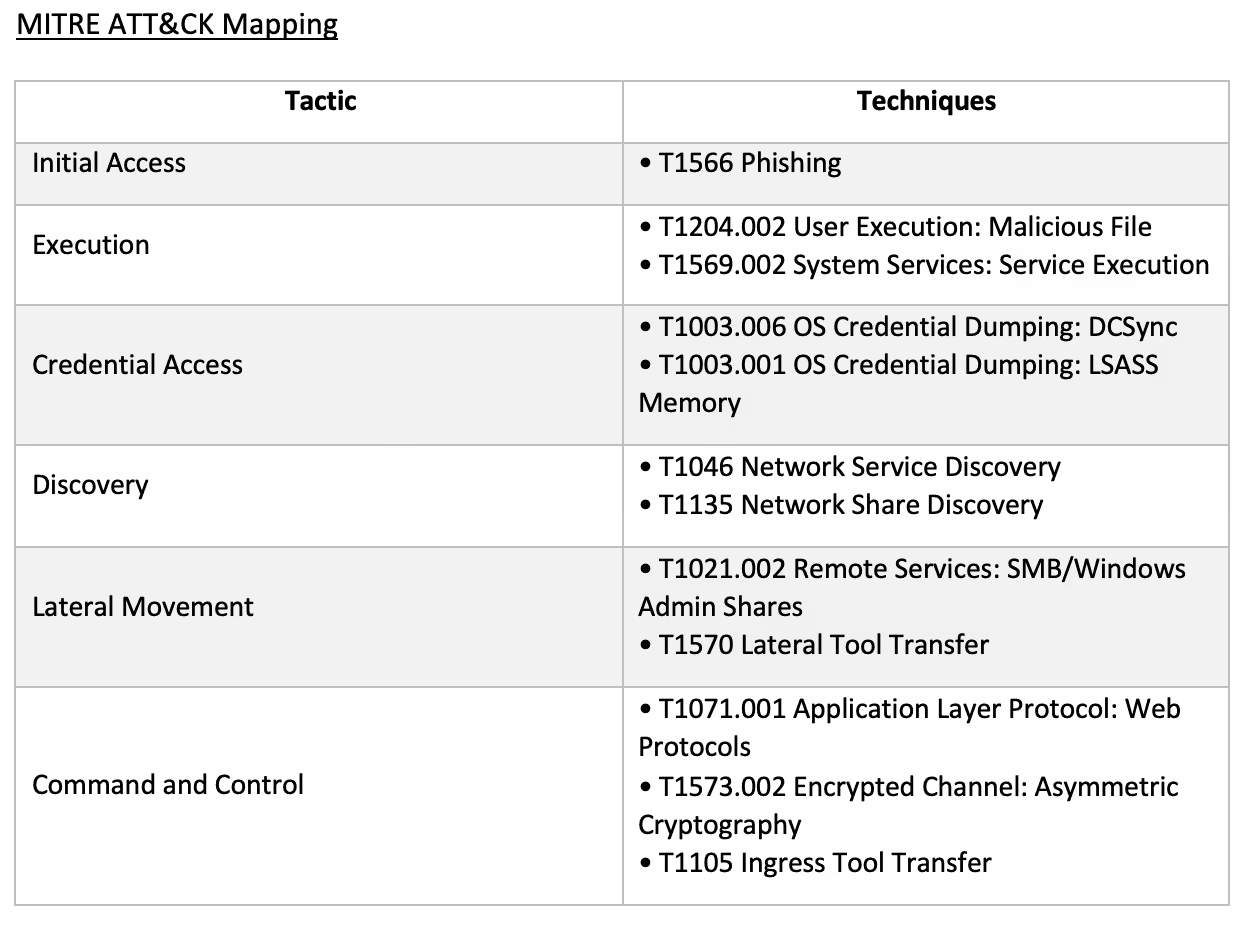

In April 2022, Darktrace observed the following pattern of threat actor activity within the networks of several Darktrace clients:

1. Threat actor socially engineers user via email into running a BumbleBee payload on their device

2. BumbleBee establishes HTTPS communication with a BumbleBee C2 server

3. Threat actor instructs BumbleBee to download and execute Cobalt Strike Beacon

4. Cobalt Strike Beacon establishes HTTPS communication with a Cobalt Strike C2 server

5. Threat actor instructs Cobalt Strike Beacon to scan for open ports and to enumerate network shares

6. Threat actor instructs Cobalt Strike Beacon to use the DCSync technique to obtain password account data from an internal domain controller

7. Threat actor instructs Cobalt Strike Beacon to distribute malicious payloads to other internal systems

With limited visibility over affected clients’ email environments, Darktrace was unable to determine how the threat actors interacted with users to initiate the BumbleBee infection. However, based on open-source reporting on BumbleBee [3]/[4]/[10]/[11]/[12]/[13]/[14]/[15]/[16]/[17], it is likely that the actors tricked target users into running BumbleBee by sending them emails containing either a malicious zipped ISO file or a link to a file storage service hosting the malicious zipped ISO file. These ISO files typically contain a LNK file and a BumbleBee DLL payload. The properties of these LNK files are set in such a way that opening them causes the corresponding DLL payload to run.

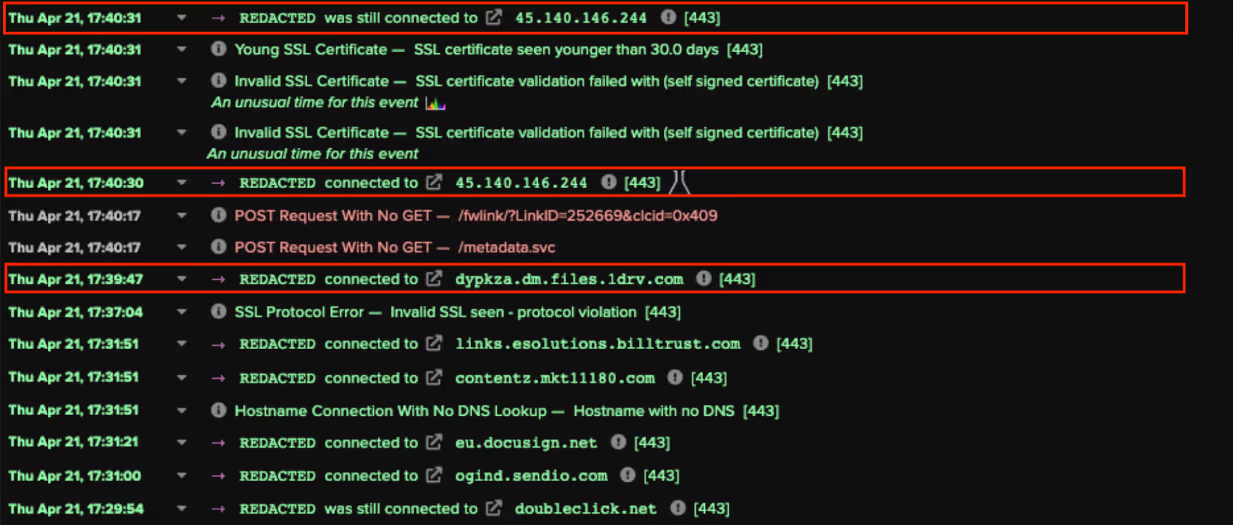

In several cases observed by Darktrace, devices contacted a file storage service such as Microsoft OneDrive or Google Cloud Storage immediately before they displayed signs of BumbleBee infection. In these cases, it is likely that BumbleBee was executed on the users’ devices as a result of the users interacting with an ISO file which they were tricked into downloading from a file storage service.

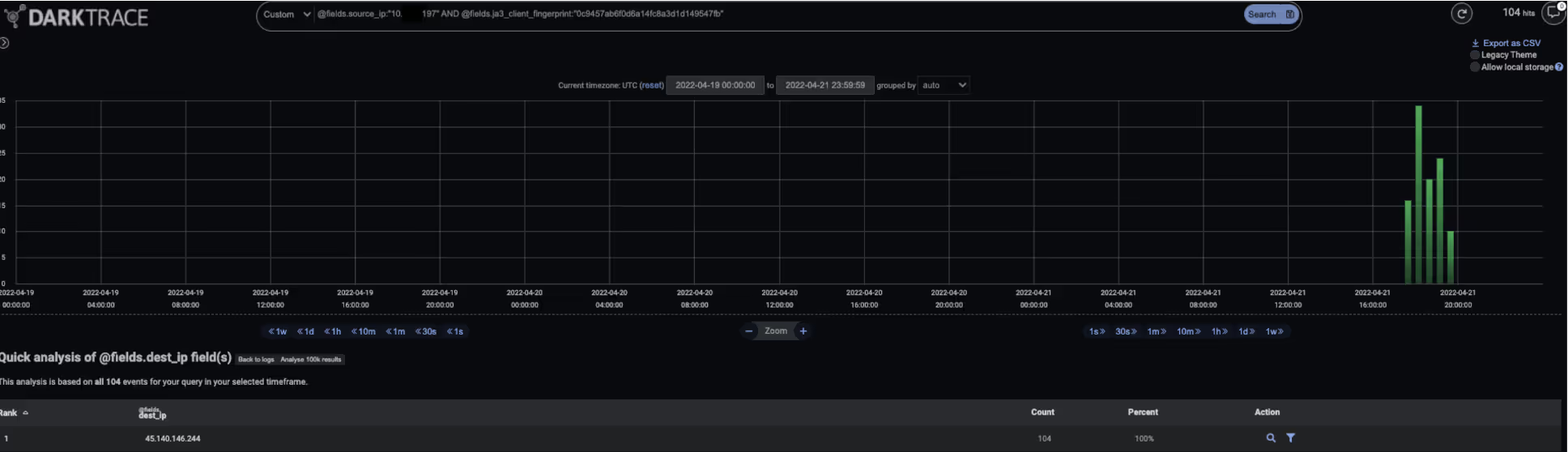

After users ran a BumbleBee payload, their devices immediately initiated communications with BumbleBee C2 servers. The BumbleBee samples used HTTPS for their C2 communication, and all presented a common JA3 client fingerprint, ‘0c9457ab6f0d6a14fc8a3d1d149547fb’. All analysed samples excluded domain names in their ‘client hello’ messages to the C2 servers, which is unusual for legitimate HTTPS communication. External SSL connections which do not specify a destination domain name and whose JA3 client fingerprint is ‘0c9457ab6f0d6a14fc8a3d1d149547fb’ are potential indicators of BumbleBee infection.

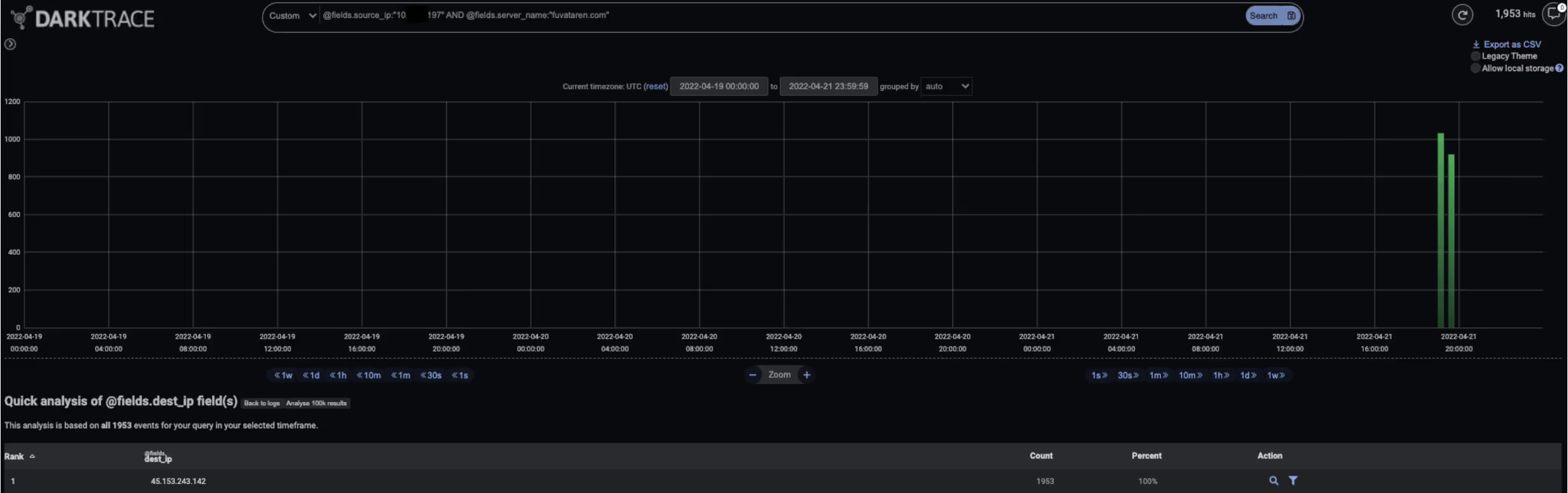

Once the threat actors had established HTTPS communication with the BumbleBee-infected systems, they instructed BumbleBee to download and execute Cobalt Strike Beacon. This behaviour resulted in the infected systems making HTTPS connections to Cobalt Strike C2 servers. The Cobalt Strike Beacon samples all had the same JA3 client fingerprint ‘a0e9f5d64349fb13191bc781f81f42e1’ — a fingerprint associated with previously seen Cobalt Strike samples [18]. The domain names ‘fuvataren[.]com’ and ‘cuhirito[.]com’ were observed in the samples’ HTTPS communications.

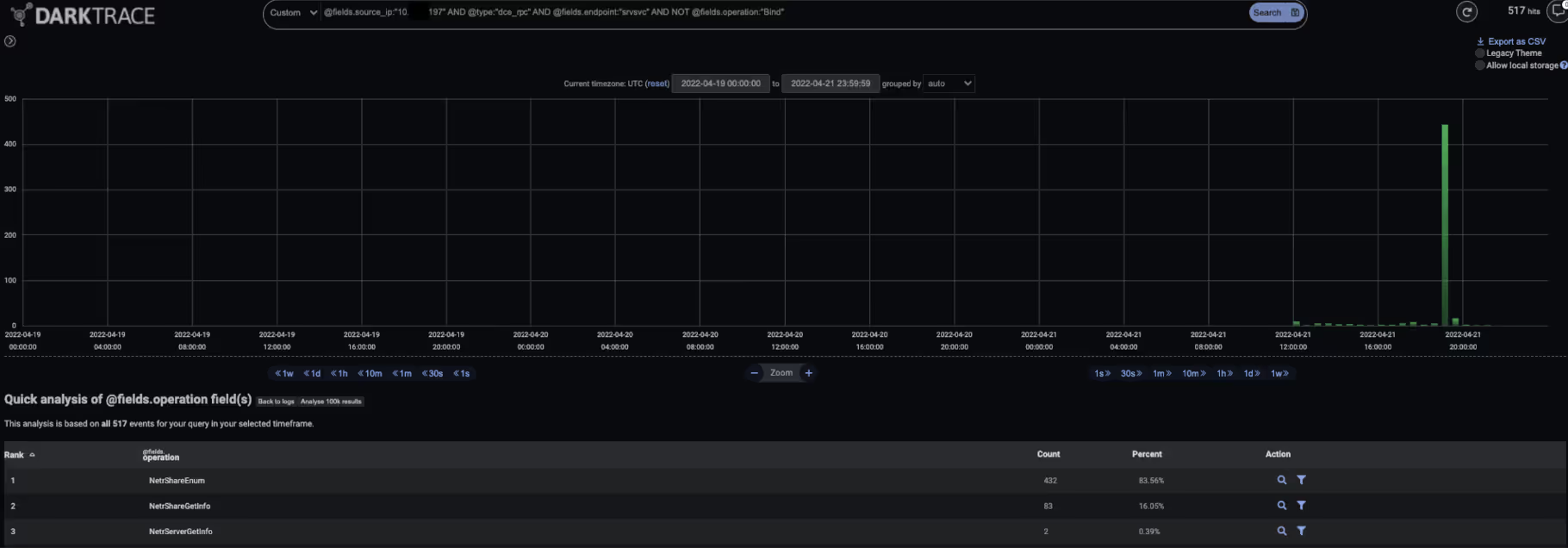

Cobalt Strike Beacon payloads call home to C2 servers for instructions. In the cases observed, threat actors first instructed the Beacon payloads to perform reconnaissance tasks, such as SMB port scanning and SMB enumeration. It is likely that the threat actors performed these steps to inform the next stages of their operations. The SMB enumeration activity was evidenced by the infected devices making NetrShareEnum and NetrShareGetInfo requests to the srvsvc RPC interface on internal systems.

After providing Cobalt Strike Beacon with reconnaissance tasks, the threat actors set out to obtain account password data in preparation for the lateral movement phase of their operation. To obtain account password data, the actors instructed Cobalt Strike Beacon to use the DCSync technique to replicate account password data from an internal domain controller. This activity was evidenced by the infected devices making DRSGetNCChanges requests to the drsuapi RPC interface on internal domain controllers.

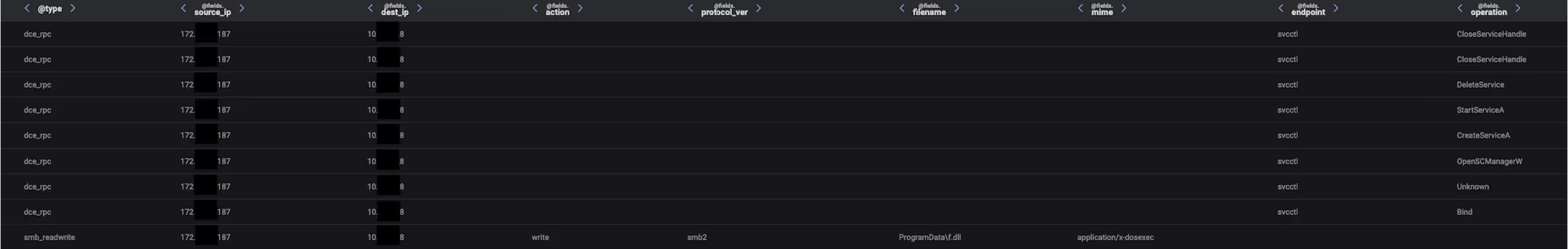

After leveraging the DCSync technique, the threat actors sought to broaden their presence within the targeted networks. To achieve this, they instructed Cobalt Strike Beacon to get several specially selected internal systems to run a suspiciously named DLL (‘f.dll’). Cobalt Strike first established SMB sessions with target systems using compromised account credentials. During these sessions, Cobalt Strike uploaded the malicious DLL to a hidden network share. To execute the DLL, Cobalt Strike abused the Windows Service Control Manager (SCM) to remotely control and manipulate running services on the targeted internal hosts. Cobalt Strike first opened a binding handle to the svcctl interface on the targeted destination systems. It then went on to make an OpenSCManagerW request, a CreateServiceA request, and a StartServiceA request to the svcctl interface on the targeted hosts:

· Bind request – opens a binding handle to the relevant RPC interface (in this case, the svcctl interface) on the destination device

· OpenSCManagerW request – establishes a connection to the Service Control Manager (SCM) on the destination device and opens a specified SCM database

· CreateServiceA request – creates a service object and adds it to the specified SCM database

· StartServiceA request – starts a specified service

It is likely that the DLL file which the threat actors distributed was a Cobalt Strike payload. In one case, however, the threat actor was also seen distributing and executing a payload named ‘procdump64.exe’. This may suggest that the threat actor was seeking to use ProcDump to obtain authentication material stored in the process memory of the Local Security Authority Subsystem Service (LSASS). Given that ProcDump is a legitimate Windows Sysinternals tool primarily used for diagnostics and troubleshooting, it is likely that threat actors leveraged it in order to evade detection.

In all the cases which Darktrace observed, threat actors’ attempts to conduct follow-up activities after moving laterally were thwarted with the help of Darktrace’s SOC team. It is likely that the threat actors responsible for the reported activities were seeking to deploy ransomware within the targeted networks. The steps which the threat actors took to make progress towards achieving this objective resulted in highly unusual patterns of network traffic. Darktrace’s detection of these unusual network activities allowed security teams to prevent these threat actors from achieving their disruptive objectives.

Darktrace Coverage

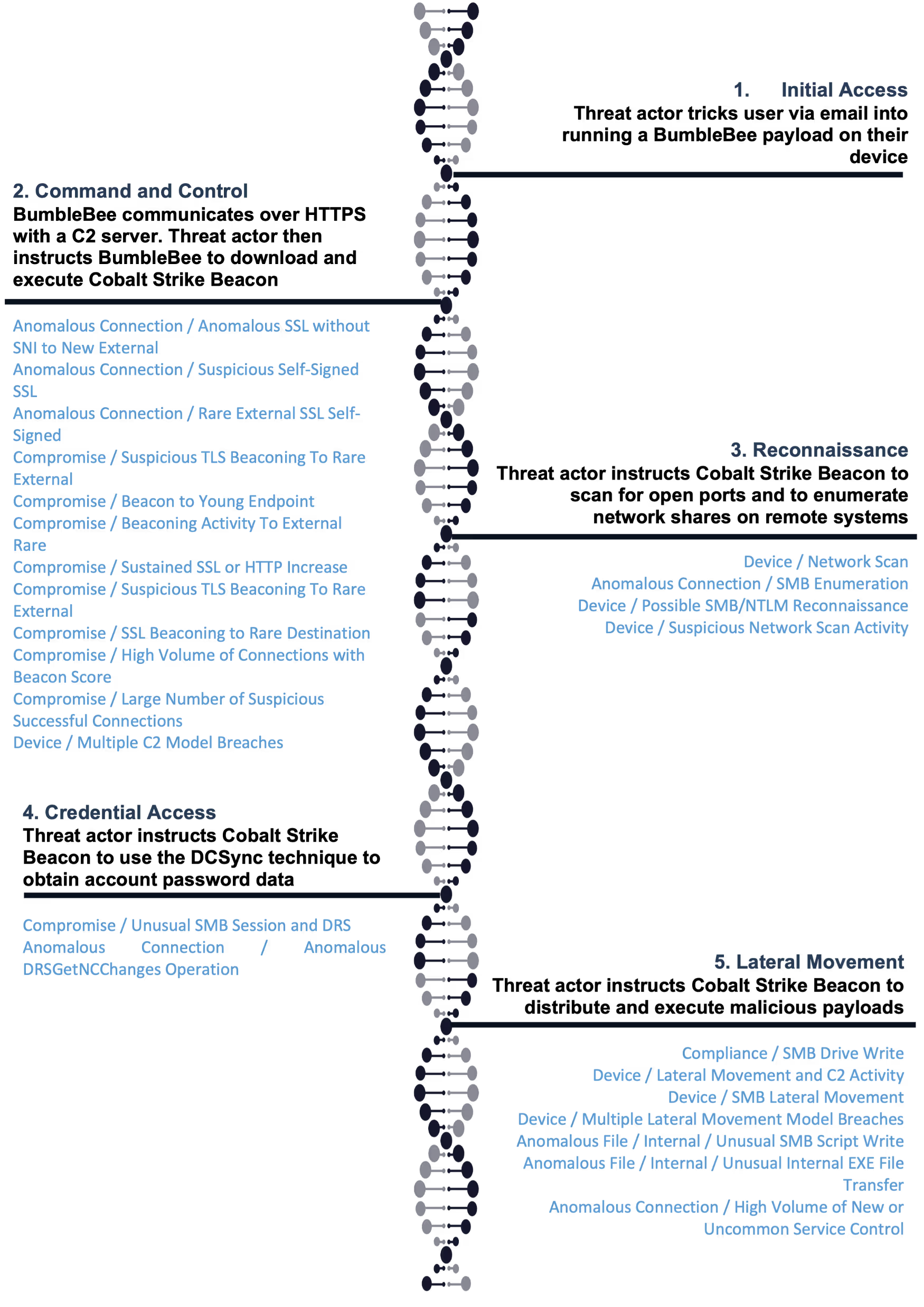

Once threat actors succeeded in tricking users into running BumbleBee on their devices, Darktrace’s Self-Learning AI immediately detected the command-and-control (C2) activity generated by the loader. BumbleBee’s C2 activity caused the following Darktrace models to breach:

· Anomalous Connection / Anomalous SSL without SNI to New External

· Anomalous Connection / Suspicious Self-Signed SSL

· Anomalous Connection / Rare External SSL Self-Signed

· Compromise / Suspicious TLS Beaconing To Rare External

· Compromise / Beacon to Young Endpoint

· Compromise / Beaconing Activity To External Rare

· Compromise / Sustained SSL or HTTP Increase

· Compromise / Suspicious TLS Beaconing To Rare External

· Compromise / SSL Beaconing to Rare Destination

· Compromise / Large Number of Suspicious Successful Connections

· Device / Multiple C2 Model Breaches

BumbleBee’s delivery of Cobalt Strike Beacon onto target systems resulted in those systems communicating with Cobalt Strike C2 servers. Cobalt Strike Beacon’s C2 communications resulted in breaches of the following models:

· Compromise / Beaconing Activity To External Rare

· Compromise / High Volume of Connections with Beacon Score

· Compromise / Large Number of Suspicious Successful Connections

· Compromise / Sustained SSL or HTTP Increase

· Compromise / SSL or HTTP Beacon

· Compromise / Slow Beaconing Activity To External Rare

· Compromise / SSL Beaconing to Rare Destination

The threat actors’ subsequent port scanning and SMB enumeration activities caused the following models to breach:

· Device / Network Scan

· Anomalous Connection / SMB Enumeration

· Device / Possible SMB/NTLM Reconnaissance

· Device / Suspicious Network Scan Activity

The threat actors’ attempts to obtain account password data from domain controllers using the DCSync technique resulted in breaches of the following models:

· Compromise / Unusual SMB Session and DRS

· Anomalous Connection / Anomalous DRSGetNCChanges Operation

Finally, the threat actors’ attempts to internally distribute and execute payloads resulted in breaches of the following models:

· Compliance / SMB Drive Write

· Device / Lateral Movement and C2 Activity

· Device / SMB Lateral Movement

· Device / Multiple Lateral Movement Model Breaches

· Anomalous File / Internal / Unusual SMB Script Write

· Anomalous File / Internal / Unusual Internal EXE File Transfer

· Anomalous Connection / High Volume of New or Uncommon Service Control

If Darktrace/Network had been configured in the targeted environments, then it would have blocked BumbleBee’s C2 communications, which would have likely prevented the threat actors from delivering Cobalt Strike Beacon into the target networks.

Conclusion

Threat actors use loaders to smuggle more harmful payloads into target networks. Prior to March 2022, it was common to see threat actors using the BazarLoader loader to transfer their payloads into target environments. However, since the public disclosure of the Conti gang’s Jabber chat logs at the end of February, the cybersecurity world has witnessed a shift in tradecraft. Threat actors have seemingly transitioned from using BazarLoader to using a novel loader known as ‘BumbleBee’. Since BumbleBee first made an appearance in March 2022, a growing number of threat actors, in particular ransomware actors, have been observed using it.

It is likely that this trend will continue, which makes the detection of BumbleBee activity vital for the prevention of ransomware deployment within organisations’ networks. During April, Darktrace’s SOC team observed a particular pattern of threat actor activity involving the BumbleBee loader. After tricking users into running BumbleBee on their devices, threat actors were seen instructing BumbleBee to drop Cobalt Strike Beacon. Threat actors then leveraged Cobalt Strike Beacon to conduct network reconnaissance, obtain account password data from internal domain controllers, and distribute malicious payloads internally. Darktrace’s detection of these activities prevented the threat actors from achieving their likely harmful objectives.

Thanks to Ross Ellis for his contributions to this blog.

Appendices

References

[1] https://blog.google/threat-analysis-group/exposing-initial-access-broker-ties-conti/

[2] https://securityintelligence.com/posts/trickbot-gang-doubles-down-enterprise-infection/

[3] https://www.proofpoint.com/us/blog/threat-insight/bumblebee-is-still-transforming

[4] https://www.cynet.com/orion-threat-alert-flight-of-the-bumblebee/

[5] https://research.nccgroup.com/2022/04/29/adventures-in-the-land-of-bumblebee-a-new-malicious-loader/

[7] https://therecord.media/conti-leaks-the-panama-papers-of-ransomware/

[8] https://www.secureworks.com/blog/gold-ulrick-leaks-reveal-organizational-structure-and-relationships

[9] https://www.prodaft.com/m/reports/Conti_TLPWHITE_v1.6_WVcSEtc.pdf

[11] https://symantec-enterprise-blogs.security.com/blogs/threat-intelligence/bumblebee-loader-cybercrime

[13] https://isc.sans.edu/diary/rss/28664

[15] https://ghoulsec.medium.com/mal-series-23-malware-loader-bumblebee-6ab3cf69d601

[16] https://blog.cyble.com/2022/06/07/bumblebee-loader-on-the-rise/

[17] https://asec.ahnlab.com/en/35460/

[18] https://thedfirreport.com/2021/07/19/icedid-and-cobalt-strike-vs-antivirus/