In early December 2020, Darktrace AI autonomously detected and investigated a sophisticated cyber-attack that targeted a customer’s Exchange server. On March 2, 2021, Microsoft disclosed an ongoing campaign by the Hafnium threat actor group leveraging Exchange server zero-days.

Based on similarities in techniques, tools and procedures (TTPs) observed, Darktrace has now assessed with high confidence that the attack in December was the work of the Hafnium group. Although it is not possible to determine whether this attack leveraged the same Exchange zero-days as reported by Microsoft, the finding suggests that Hafnium’s campaign was active several months earlier than assumed.

As a result, organizations may want to go back as far as early December 2020 to check security logs and tools for signs of initial intrusion into their Internet-facing Exchange servers.

As Darktrace does not rely on rules or signatures, it doesn’t require a constant cloud connection. Most customers therefore operate our technology themselves, and we don’t centrally monitor their detections.

At the time of detection in December, this was one of many uncategorized, sophisticated intrusions that affected only a single customer, and was not indicative of a broader campaign.

This means that while we protect our customers from individual intrusions, we are not in a position to do global campaign tracking like other companies which focus primarily on threat intelligence and threat actor tracking.

In this blog, we will analyze the attack to aid organizations in their ongoing investigations, and to raise awareness that the Hafnium campaign may have been active for longer than previously disclosed.

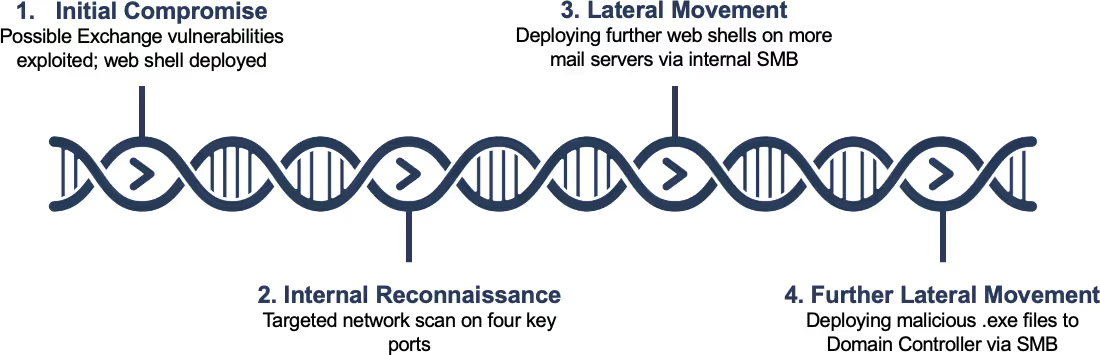

Overview of the Exchange attack

The intrusion was detected at an organization in the critical national infrastructure sector in South Asia. One hypothesis is that the Hafnium group was testing out and refining its TTPs, potentially including the Exchange server exploit, before running a broad-scale campaign against Western organizations in early 2021.

The threat actor used many of the same techniques that were observed in the later Hafnium attacks, including the deployment of the low-activity China Chopper web shell, quickly followed by post-exploitation activity – attempting to move laterally and spread to critical devices in the network.

The following analysis demonstrates how Darktrace’s Enterprise Immune System detected the malicious activity, how Cyber AI Analyst automatically investigated on the incident and surfaced the alert as a top priority, and how Darktrace RESPOND (formerly known as 'Antigena') would have responded autonomously to shut down the attack, had it been in active mode.

All the activity took place in early December 2020, almost three months before Microsoft released information about the Hafnium campaign.

Initial compromise

Unfortunately, the victim organization did not keep any logs or forensic artefacts from their Exchange server in December 2020, which would have allowed Darktrace to ascertain the exploit of the zero-day. However, there is circumstantial evidence suggesting that these Exchange server vulnerabilities were abused.

Darktrace observed no signs of compromise or change in behavior from the Internet-facing Exchange server – no prior internal admin connections, no broad-scale brute-force attempts, no account takeovers, no malware copied to the server via internal channels – until all of a sudden, it began to scan the internal network.

While this is not conclusive evidence that no other avenue of initial intrusion was present, the change in behavior on an administrative level points to a complete takeover of the Exchange server, rather than the compromise of a single Outlook Web Application account.

To conduct a network scan from an Exchange server, a highly privileged, operating SYSTEM-level account is required. The patch level of the Exchange server at the time of compromise appears to have been up-to-date, at least not offering a threat actor the ability to target a known vulnerability to instantly get SYSTEM-level privileges.

For this reason, Darktrace has inferred that the Exchange server zero-days that became public in early March 2021 were possibly being used in this attack observed in early December 2020.

Internal reconnaissance

As soon as the attackers gained access via the web shell, they used the Exchange server to scan all IPs in a single subnet on ports 80, 135, 445, 8080.

This particular Exchange server had never made such a large number of new failed internal connections to that specific subnet on those key ports. As a result, Darktrace instantly alerted on the anomalous behavior, which was indicative of a network scan.

Autonomous Response

Darktrace RESPOND was in passive mode in the environment, so was not able to take action. In active mode, it would have responded by enforcing the previously learned, normal ‘pattern of life’ of the Exchange server – allowing the server to continue normal business operations (sending and receiving emails) but preventing the network scan and any subsequent activity. These actions would have been carried out via various integrations with the customer’s existing security stack, including Firewalls and Network Access Controls.

Specifically, when the network scanning started, the ‘Antigena Network Scan Block’ was triggered. This means that for several hours, Darktrace RESPOND (Antigena) would have blocked any new outgoing connections from the Exchange server to the scanned subnet on port 80, 135, 445, or 8080, preventing the infected Exchange server from conducting network scanning.

As a result, the attackers would not have been able to conclude anything from their reconnaissance — all their scanning would have returned closed ports. At this point, they would need to stop their attack or resort to other means, likely triggering further detections and further Autonomous Response.

The network scan was the first step touching the internal network. This is therefore a clear case of how Darktrace RESPOND can intercept an attack in seconds, acting at the earliest possible evidence of the intrusion.

Lateral movement

Less than an hour after the internal network scan, the compromised Exchange server was observed writing further web shells to other Exchange servers via internal SMB. Darktrace alerted on this as the initially compromised Exchange server had never accessed the other Exchange servers in this fashion over SMB, let alone writing .aspx files to Program Files remotely.

A single click allowed the security team to pivot from the alert into Darktrace’s Advanced Search, revealing further details about the written files. The full file path for the newly deployed web shells was:

Program Files\Microsoft\Exchange Server\V15\FrontEnd\HttpProxy\owa\auth\Current\themes\errorFS.aspx

The attackers thus used internal SMB to compromise further Exchange servers and deploy more web shells, rather than using the Exchange zero-day exploit again to achieve the same goal. The reason for this is clear: exploits can often be unstable, and an adversary would not want to show their hand unnecessarily if it could be avoided.

While the China Chopper web shell has been deployed with many different names in the past, the file path and file name of the actual .aspx web shell bear very close resemblance to the Hafnium campaign details published by Microsoft and others in March 2021.

As threat actors often reuse naming conventions / TTPs in coherent campaigns, it again indicates that this particular attack was in some way part of the broader campaign observed in early 2021.

Further lateral movement

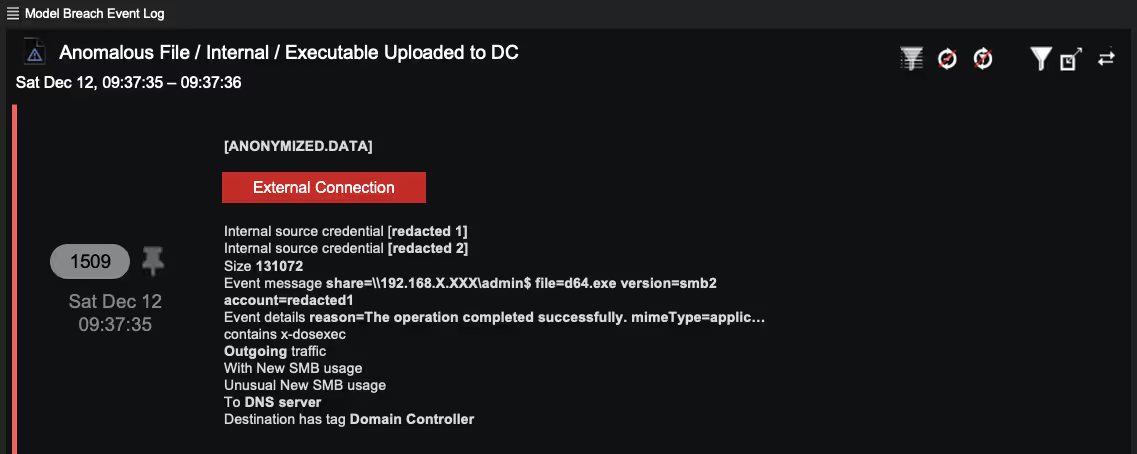

Minutes later, the attacker conducted further lateral movement by making more SMB drive writes to Domain Controllers. This time the attackers did not upload web shells, but malware, in the form of executables and Windows .bat files.

Darktrace alerted the security team as it was extremely unusual for the Exchange server and its peer group to make SMB drive writes to hidden shares to a Domain Controller, particularly using executables and batch files. The activity was presented to the team in the form of a high-confidence alert such as the anonymized example below.

The batch file was called ‘a.bat’. At this point, the security team could have created a packet capture for the a.bat file in Darktrace with the click of a button, inspecting the content and details of that script at the time of the intrusion.

Darktrace also listed the credentials involved in the activity, providing context into the compromised accounts. This allows an analyst to pivot rapidly around the data and further understand the scope of the intrusion.

Bird’s-eye perspective

In addition to detecting the malicious activity outlined above, Darktrace’s Cyber AI Analyst autonomously summarized the incident and reported on it, outlining the internal reconnaissance and lateral movement activity in a single, cohesive incident.

The organization has several thousand devices covered by Darktrace’s Enterprise Immune System. Nevertheless, over the period of one week, the Hafnium intrusion was in the top five incidents highlighted in Cyber AI Analyst. Even a small or resource-stretched security team, with only a few minutes available per week to review the highest-severity incidents, could have seen and inspected this threat.

Below is a graphic showing a similar Cyber AI Analyst incident created by Darktrace.

How to stop a zero-day

Large scale campaigns which target Internet-facing infrastructure and leverage zero-day exploits will continue to occur regularly, and such attacks will always succeed in evading signature-based detection. However, organizations are not helpless against the next high-profile zero-day or supply chain attack.

Detecting the movements of attackers inside a system and responding to contain in-progress threats is possible before IoCs have been provided. The methods of detection outlined above protected the company against this attack in December, and the same techniques will continue to protect the company against unknown threats in the future.

Learn more about how Darktrace AI has stopped Hafnium cyber-attacks and similar threat actors

Darktrace model detections:

- Device / New or Uncommon WMI Activity

- Executable Uploaded to DC

- Compliance / High Priority Compliance Model Breach

- Compliance / SMB Drive Write

- Antigena / Network / Insider Threat / Antigena Network Scan Block

- Device / Network Scan - Low Anomaly Score

- Unusual Activity / Unusual Internal Connections