Fighting Info-Stealing Malware

The escalating threat posed by information-stealing malware designed to harvest and steal the sensitive data of individuals and organizations alike has become a paramount concern for security teams across the threat landscape. In direct response to security teams improving their threat detection and prevention capabilities, threat actors are forced to continually adapt and advance their techniques, striving for greater sophistication to ensure they can achieve the malicious goals.

What is ViperSoftX?

ViperSoftX is an information stealer and Remote Access Trojan (RAT) malware known to steal privileged information such as cryptocurrency wallet addresses and password information stored in browsers and password managers. It is commonly distributed via the download of cracked software from multiple sources such as suspicious domains, torrent downloads, and key generators (keygens) from third-party sites.

ViperSoftX was first observed in the wild in 2020 [1] but more recently, new strains were identified in 2022 and 2023 utilizing more sophisticated detection evasion techniques, making it more difficult for security teams to identify and analyze. This includes using more advanced encryption methods alongside monthly changes to command-and-control servers (C2) [2], using dynamic-link library (DLL) sideloading for execution techiques, and subsequently loading a malicious browser extension upon infection which works as an independent info-stealer named VenomSoftX [3].

Between February and June 2023, Darktrace detected activity related to the VipersoftX and VenomSoftX information stealers on the networks of more than 100 customers across its fleet. Darktrace DETECT™ was able to successfully identify the anomalous network activity surrounding these emerging information stealer infections and bring them to the attention of the customers, while Darktrace RESPOND™, when enabled in autonomous response mode, was able to quickly intervene and shut down malicious downloads and data exfiltration attempts.

ViperSoftX Attack & Darktrace Coverage

In cases of ViperSoftX information stealer activity observed by Darktrace, the initial infection was caused through the download of malicious files from multimedia sites, endpoints of cracked software like Adobe Illustrator, and torrent sites. Endpoint users typically unknowingly download the malware from these endpoints with a sideloaded DLL, posing as legitimate software executables.

Darktrace detected multiple downloads from such multimedia sites and endpoints related to cracked software and BitTorrent, which were likely representative of the initial source of ViperSoftX infection. Darktrace DETECT models such as ‘Anomalous File / Anomalous Octet Stream (No User Agent)’ breached in response to this activity and were brought to the immediate attention of customer security teams. In instances where Darktrace RESPOND was configured in autonomous response mode, Darktrace was able to enforce a pattern of life on offending devices, preventing them from downloading malicious files. This ensures that devices are limited to conducting only their pre-established expected activit, minimizing disruption to the business whilst targetedly mitigating suspicious file downloads.

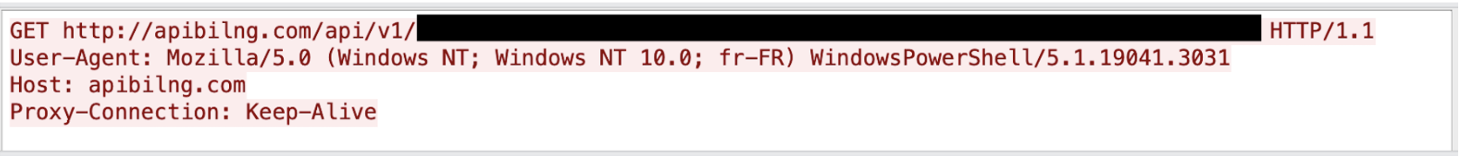

The downloads are then extracted, decrypted and begin to run on the device. The now compromised device will then proceed to make external connections to C2 servers to retrieve secondary PowerShell executable. Darktrace identified that infected devices using PowerShell user agents whilst making HTTP GET requests to domain generation algorithm (DGA) ViperSoftX domains represented new, and therefore unusual, activity in a large number of cases.

For example, Darktrace detected one customer device making an HTTP GET request to the endpoint ‘chatgigi2[.]com’, using the PowerShell user agent ‘Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT; Windows NT 10.0; en-US) WindowsPowerShell/5.1.19041.2364’. This new activity triggered a number of DETECT models, including ‘Anomalous Connection / PowerShell to Rare External’ and ‘Device / New PowerShell User Agent’. Repeated connections to these endpoints also triggered C2 beaconing models including:

- Compromise / Agent Beacon (Short Period)

- Compromise / Agent Beacon (Medium Period)

- Compromise / Agent Beacon (Long Period)

- Compromise / Quick and Regular Windows HTTP Beaconing

- Compromise / SSL or HTTP Beacon

Although a large number of different DGA domains were detected, commonalities in URI formats were seen across affected customers which matched formats previously identified as ViperSoftX C2 communication by open-source intelligence (OSINT), and in other Darktrace investigations.

URI paths for example, were always of the format /api/, /api/v1/, /v2/, or /v3/, appearing to detail version number, as can be seen in Figure 1.

Before the secondary PowerShell executables are loaded, ViperSoftX takes a digital fingerprint of the infected machine to gather its configuration details, and exfiltrates them to the C2 server. These include the computer name, username, Operating System (OS), and ensures there are no anti-virus or montoring tools on the device. If no security tool are detected, ViperSoftX then downloads, decrypts and executes the PowerShell file.

Following the GET requests Darktrace observed numerous devices performing HTTP POST requests and beaconing connections to ViperSoftX endpoints with varying globally unique identifiers (GUIDs) within the URIs. These connections represented the exfiltration of device configuration details, such as “anti-virus detected”, “app used”, and “device name”. As seen on another customer’s deployment, this caused the model ‘Anomalous Connection / Multiple HTTP POSTs to Rare Hostname’ to breach, which was also detected by Cyber AI Analyst as seen in Figure 2.

The malicious PowerShell download then crawls the infected device’s systems and directories looking for any cryptocurrency wallet information and password managers, and exfiltrates harvest data to the C2 infrastructure. The C2 server then provides further browser extensions to Chromium browsers to be downloaded and act as a separate stand-alone information stealer, also known as VenomSoftX.

Similar to the initial download of ViperSoftX, these malicious extensions are disguised as legitimate browser extensions to evade the detection of security teams. VenomSoft X, in turn, searches through and attempts to gather sensitive data from password managers and crypto wallets stored in user browsers. Using this information, VenomSoftX is able to redirect crypocurrency transactions by intercepting and manipulating API requests between the sender and the intended recipient, directing the cryptocurrency to the attacker instead [3].

Following investigation into VipersoftX activity across the customer base, Darktrace notified all affected customers and opened Ask the Expert (ATE) tickets through which customer’s could directly contact the analyst team for support and guidance in the face on the information stealer infection.

How did the attack bypass the rest of the security stack?

As previously mentioned, both the initial download of ViperSoftX and the subsequent download of the VenomX browser extension are disguised as legitimate software or browser downloads. This is a common technique employed by threat actors to infect target devices with malicious software, while going unnoticed by security teams traditional security measures. Furthermore, by masquerading as a legitimate piece of software endpoint users are more likely to trust and therefore download the malware, increasing the likelihood of threat actor’s successfully carrying out their objectives. Additionally, post-infection analysis of shellcode, the executable code used as the payload, is made significantly more difficult by VenomSoftX’s use of bytemapping. Bytemapping prevents the encryption of shellcodes without its corresponding byte map, meaning that the payloads cannot easily be decrypted and analysed by security researchers. [3]

ViperSoftX also takes numerous attempts to prevent their C2 infrastructure from being identified by blocking access to it on browsers, and using multiple DGA domains, thus renderring defunct traditional security measures that rely on threat intelligence and static lists of indicators of compromise (IoCs).

Fortunately for Darktrace customers, Darktrace’s anomaly-based approach to threat detection means that it was able to detect and alert customers to this suspicious activity that may have gone unnoticed by other security tools.

Insights/Conclusion

Faced with the challenge of increasingly competent and capable security teams, malicious actors are having to adopt more sophisticated techniques to successfully compromise target systems and achieve their nefarious goals.

ViperSoftX information stealer makes use of numerous tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) designed to fly under the radar and carry out their objectives without being detected. ViperSoftX does not rely on just one information stealing malware, but two with the subsequent injection of the VenomSoftX browser extension, adding an additional layer of sophistication to the informational stealing operation and increasing the potential yield of sensitive data. Furthermore, the use of evasion techniques like disguising malicious file downloads as legitimate software and frequently changing DGA domains means that ViperSoftX is well equipped to infiltrate target systems and exfiltrate confidential information without being detected.

However, the anomaly-based detection capabilities of Darktrace DETECT allows it to identify subtle changes in a device’s behavior, that could be indicative of an emerging compromise, and bring it to the customer’s security team. Darktrace RESPOND is then autonomously able to take action against suspicious activity and shut it down without latency, minimizing disruption to the business and preventing potentially significant financial losses.

Credit to: Zoe Tilsiter, Senior Cyber Analyst, Nathan Lorenzo, Cyber Analyst.

Appendices

References

[1] https://www.fortinet.com/blog/threat-research/vipersoftx-new-javascript-threat

[2] https://www.trendmicro.com/en_us/research/23/d/vipersoftx-updates-encryption-steals-data.html

[3] https://decoded.avast.io/janrubin/vipersoftx-hiding-in-system-logs-and-spreading-venomsoftx/

Darktrace DETECT Model Detections

· Anomalous File / Anomalous Octet Stream (No User Agent)

· Anomalous Connection / PowerShell to Rare External

· Anomalous Connection / Multiple HTTP POSTs to Rare Hostname

· Anomalous Connection / Lots of New Connections

· Anomalous Connection / Multiple Failed Connections to Rare Endpoint

· Anomalous Server Activity / Outgoing from Server

· Compromise / Large DNS Volume for Suspicious Domain

· Compromise / Quick and Regular Windows HTTP Beaconing

· Compromise / Beacon for 4 Days

· Compromise / Suspicious Beaconing Behaviour

· Compromise / Large Number of Suspicious Failed Connections

· Compromise / Large Number of Suspicious Successful Connections

· Compromise / POST and Beacon to Rare External

· Compromise / DGA Beacon

· Compromise / Agent Beacon (Long Period)

· Compromise / Agent Beacon (Medium Period)

· Compromise / Agent Beacon (Short Period)

· Compromise / Fast Beaconing to DGA

· Compromise / SSL or HTTP Beacon

· Compromise / Slow Beaconing Activity To External Rare

· Compromise / Beaconing Activity To External Rare

· Compromise / Excessive Posts to Root

· Compromise / Connections with Suspicious DNS

· Compromise / HTTP Beaconing to Rare Destination

· Compromise / High Volume of Connections with Beacon Score

· Compromise / Sustained SSL or HTTP Increase

· Device / New PowerShell User Agent

· Device / New User Agent and New IP

Darktrace RESPOND Model Detections

· Antigena / Network / External Threat / Antigena Suspicious File Block

· Antigena / Network / External Threat / Antigena File then New Outbound Block

· Antigena / Network / External Threat / Antigena Watched Domain Block

· Antigena / Network / Significant Anomaly / Antigena Significant Anomaly from Client Block

· Antigena / Network / External Threat / Antigena Suspicious Activity Block

· Antigena / Network / Significant Anomaly / Antigena Breaches Over Time Block

· Antigena / Network / Insider Threat / Antigena Large Data Volume Outbound Block

· Antigena / Network / External Threat / Antigena Suspicious File Pattern of Life Block

· Antigena / Network / Significant Anomaly / Antigena Controlled and Model Breach

List of IoCs

Indicator - Type - Description

ahoravideo-blog[.]com - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

ahoravideo-blog[.]xyz - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

ahoravideo-cdn[.]com - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

ahoravideo-cdn[.]xyz - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

ahoravideo-chat[.]com - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

ahoravideo-chat[.]xyz - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

ahoravideo-endpoint[.]xyz - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

ahoravideo-schnellvpn[.]com - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

ahoravideo-schnellvpn[.]xyz - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

apibilng[.]com - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

arrowlchat[.]com - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

bideo-blog[.]com - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

bideo-blog[.]xyz - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

bideo-cdn[.]com - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

bideo-cdn[.]xyz - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

bideo-chat[.]com - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

bideo-chat[.]xyz - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

bideo-endpoint[.]com - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

bideo-endpoint[.]xyz - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

bideo-schnellvpn[.]com - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

chatgigi2[.]com - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

counter[.]wmail-service[.]com - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

fairu-cdn[.]xyz - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

fairu-chat[.]xyz - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

fairu-endpoint[.]com - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

fairu-schnellvpn[.]com - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

fairu-schnellvpn[.]xyz - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

privatproxy-blog[.]com - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

privatproxy-blog[.]xyz - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

privatproxy-cdn[.]com - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

privatproxy-cdn[.]xyz - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

privatproxy-endpoint[.]xyz - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

privatproxy-schnellvpn[.]com - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

privatproxy-schnellvpn[.]xyz - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

static-cdn-349[.]net - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

wmail-blog[.]com - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

wmail-cdn[.]xyz - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

wmail-chat[.]com - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

wmail-schnellvpn[.]com - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

wmail-schnellvpn[.]xyz - Hostname - ViperSoftX C2 endpoint

Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT; Windows NT 10.0; en-US) WindowsPowerShell/5.1.19041.2364 - User Agent -PowerShell User Agent

MITRE ATT&CK Mapping

Tactic - Technique - Notes

Command and Control - T1568.002 Dynamic Resolution: Domain Generation Algorithms

Command and Control - T1321 Data Encoding

Credential Access - T1555.005 Credentials from Password Stores: Password Managers

Defense Evasion - T1027 Obfuscated Files or Information

Execution - T1059.001 Command and Scripting Interpreter: PowerShell

Execution - T1204 User Execution T1204.002 Malicious File

Persistence - T1176 Browser Extensions - VenomSoftX specific

Persistence, Privilege Escalation, Defense Evasion - T1574.002 Hijack Execution Flow: DLL Side-Loading

![Pivoting off the previous event by filtering the timeline to events within the same window using timestamp: [“2026-02-18T09:09:00Z” TO “2026-02-18T09:12:00Z”].](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/69a8a18526ca3e653316a596_Screenshot%202026-03-04%20at%201.17.50%E2%80%AFPM.png)