While SaaS and IoT devices are increasingly popular vectors of intrusion, server-side attacks remain a serious threat to organizations worldwide. With sophisticated vulnerability scanning tools, attackers can now pinpoint security flaws in seconds, finding points of entry across the attack surface. Human security teams often struggle to keep pace with the constant wave of newly documented vulnerabilities and patches.

Darktrace recently stopped a targeted cyber-attack by an unknown attacker. After the initial entry, the attacker exploited an unpatched vulnerability (CVE-2020-0618), granting a low-privileged credential the ability to remotely execute code. This enabled the attacker to spread laterally and eventually establish a foothold in the system by creating a new user account.

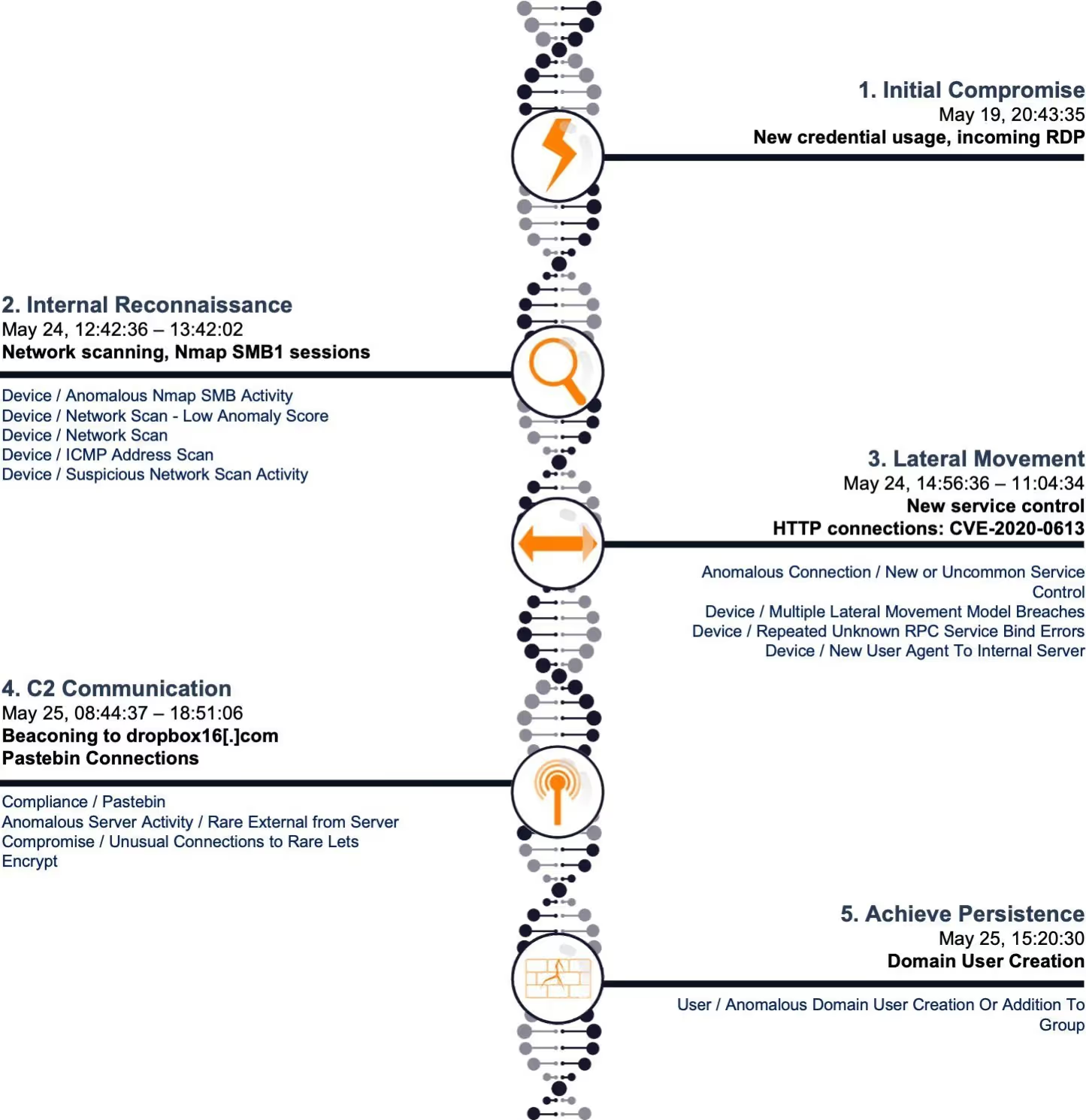

Figure 1: Overview of the server-side attack cycle.

This blog breaks down the intrusion and explores how Darktrace’s Autonomous Response technology took three surgical actions to halt the attacker’s movements.

Unknown threat actors exploit a vulnerability

Initial compromise

At a financial firm in Canada with around 3,000 devices, Cyber AI detected the use of a new credential, ‘parents’. The attacker used this credential to access the company’s internal environment through the VPN. From there, the credential authenticated to a desktop using NT LAN Manager (NTLM). No further suspicious activity was observed.

NTLM is a popular attack vector for cyber-criminals as it is vulnerable to multiple methods of compromise, including brute-force and ‘pass the hash’. The initial access to the credential could have been obtained via phishing before Darktrace had been deployed.

Figure 2: The credential was first observed on the device five days prior to reconnaissance. The attacker performed reconnaissance and lateral movement for two days, until the compromised devices were taken down.

Internal reconnaissance

Five days later, the ‘parents’ credential was seen logging onto the desktop. The desktop began scanning the network – over 80 internal IPs – on Port 443 and 445.

Shortly after the scan, the device used Nmap to attempt to establish SMBv1 sessions to 139 internal IPs, using guest / user credentials. 79 out of the 278 sessions were successful, all using the login.

Figure 3: New failed internal connections performed by an initially infected desktop, in a similar incident. The graph highlights a surge in failed internal connections and model breaches.

The network scan was the first stage after intrusion, enabling the attacker to find out which services were running, before looking for unpatched vulnerabilities.

Nmap has multiple built-in functionalities which are often exploited for reconnaissance and lateral movement. In this case, it was being used to establish the SMBv1 sessions to the domain controller, saving the attacker from having to initiate SMBv1 sessions with each destination one by one. SMBv1 has well-known vulnerabilities and best practice is to disable it where possible.

Lateral movement

The desktop began controlling services (svcctl endpoint) on a SQL server. It was observed both creating and starting services (CreateServiceW, StartServiceW).

The desktop then initiated an unencrypted HTTP connection to a SQL Reporting server. This was the first HTTP connection between the two devices and the first time the user agent had been seen on the device.

A packet capture of the connection reveals a POST that is seen in an exploit of CVE-2020-0613. This vulnerability is a deserialization issue, whereby the server mishandles carefully crafted page requests and allows low-privileged accounts to establish a reverse shell and remotely execute code on the server.

Figure 4: A partial PCAP of the HTTP connection. The traffic matches the CVE-2020-0618 exploit, which enables Remote Code Execution (RCE) in SQL Server Reporting Services (SSRS).

Most movements were seen in East-West traffic, with readily-available remote procedure call (RPC) methods. Such connections are abundant in systems. Without learning an organization’s ‘pattern of life’, it would have been near-impossible to highlight the malicious connections.

Cyber AI detected connections to the svcctl endpoint, via the DCE-RPC endpoint. This is called the 'service control' endpoint and is used to remotely control running processes on a device.

During the lateral movement from the desktop, the HTTP POST request revealed that the desktop was exploiting CVE-2020-0613. The attacker had managed to find and exploit an existing vulnerability which hadn’t been patched.

Darktrace was the only tool which alerted to the HTTP connection, revealing this underlying (and concluding) exploit. The AI determined that the user agent was unusual for the device and for the wider organization, and that the connection was highly anomalous. This connection would have gone otherwise amiss, since HTTP connections are common in most digital environments.

Because the attacker on the desktop used readily-available tools and protocols, such as Nmap, DCE-RPC, and HTTP, the device went undetected by all the other cyber defenses. However, Cyber AI noticed multiple scanning and lateral movement anomalies – triggering high-fidelity detections which would have been alerted to with Proactive Threat Notifications.

Command and control (C2) communication

The next day, the attacker connected to an SNMP server from the VPN. The connection used the ‘parents’ RDP cookie.

Immediately after the RDP connection began, the server connected to Pastebin and downloaded small amounts of encrypted data. Pastebin was likely being used as a vector to drop malicious scripts onto the device.

The SNMP server then started controlling services (svcttl) on the SQL server: again, creating and starting services.

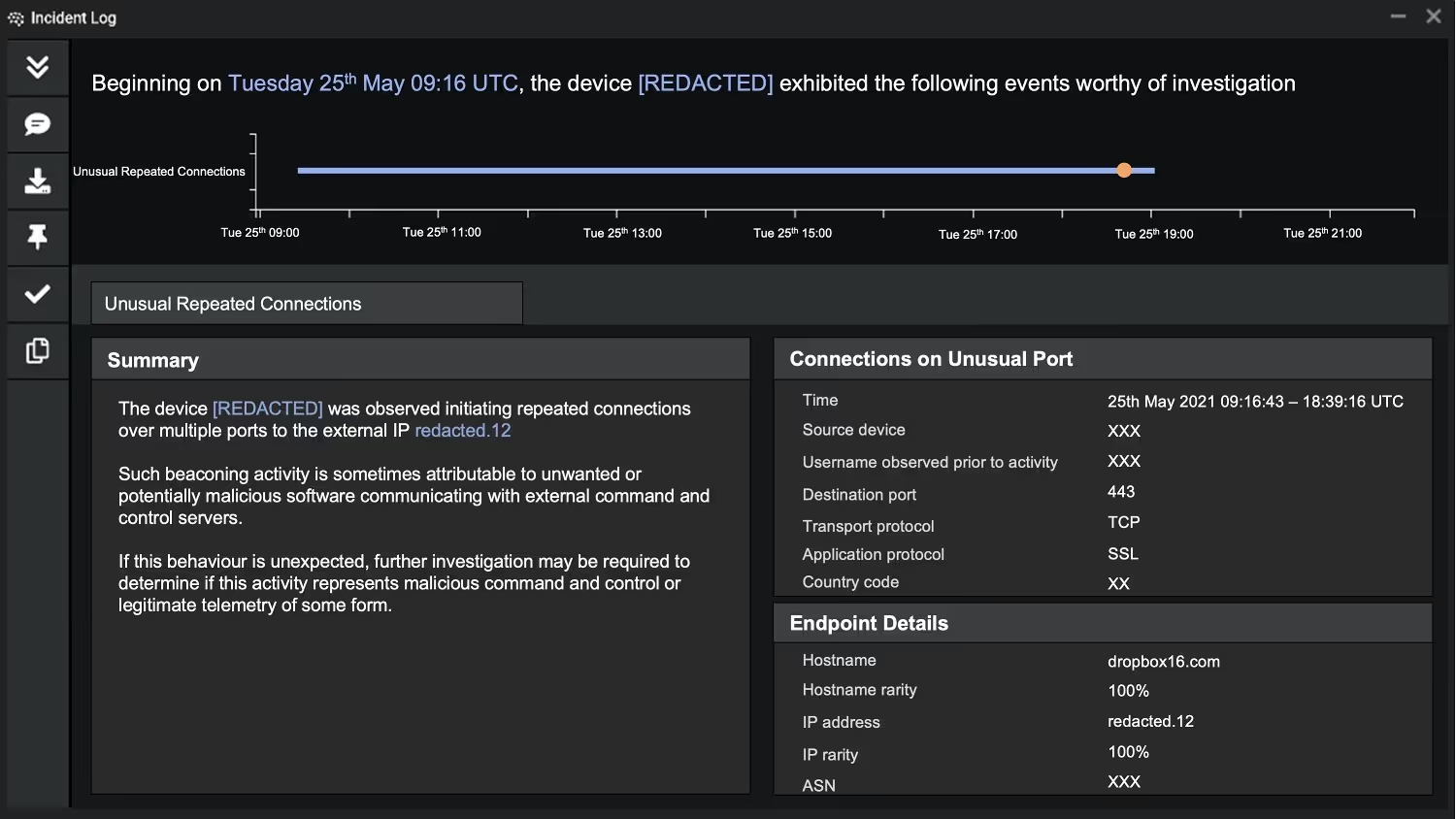

Following this, both the SQL server and the SNMP server made a high volume of SSL connections to a rare external domain. One upload to the destination was around 21 MB, but otherwise the connections were mostly the same packet size. This, among other factors, indicated that the destination was being used as a C2 server.

Figure 5: Example Cyber AI Analyst investigation into beaconing activity by a SQL server.

With just one compromised credential, the attacker was now connecting to the VPN and infecting multiple servers on the company’s internal network.

The attacker dropped scripts onto the host using Pastebin. Darktrace alerted on this because Pastebin is highly rare for the organization. In fact, these connections were the first time it had been seen. Most security tools would miss this, as Pastebin is a legitimate site and would not be blocked by open-source intelligence (OSINT).

Even if a lesser-known Pastebin alternative had been used – say, in an environment where Pastebin was blocked on the firewall but the alternative not — Darktrace would have picked up on it in exactly the same way.

The C2 beaconing endpoint – dropbox16[.]com – has no OSINT information available online. The connections were on Port 443 and nothing about them was notable except from their rarity on the company’s system. Darktrace sent alerts because of its high rarity, rather than relying on known signatures.

Achieve persistence

After another Pastebin pull, the attacker attempted to maintain a greater foothold and escalate privileges by creating a new user using the SamrCreateUser2InDomain operation (endpoint: samr).

To establish persistence, the attacker now created a new user through a specific DCE-RPC command to the domain controller. This was highly unusual activity for the device, and was given a 100% anomaly score for ‘New or Uncommon Occurrence’.

If Darktrace had not alerted on this activity, the attacker would have continued to access files and make further inroads in the company, extracting sensitive data and potentially installing ransomware. This could have led to sensitive data loss, reputational damage, and financial losses for the company.

The value of Autonomous Response

The organization had Antigena in passive mode, so although it was not able to respond autonomously, we have visibility into the actions that it would have taken.

Antigena would have taken three actions on the initially infected desktop, as shown in the table below. The actions would have taken effect immediately in response to the first scan and the first service control requests.

During the two days of reconnaissance and lateral movement activity, these were the only steps Antigena suggested. The steps were all directly relevant to the intrusion – there was no attempt to block anything unrelated to the attack, and no other Antigena actions were triggered during this period.

By surgically blocking connections on specific ports during the scanning activity and enforcing the ‘pattern of life’ on the infected desktop, Antigena would have paralyzed the attacker’s reconnaissance efforts.

Furthermore, unusual service control attempts performed by the device would have been halted, minimizing the damage to the targeted destination.

Antigena would have delivered these blocks directly or via whatever integration was most suitable for the customer, such as firewall integrations or NAC integrations.

Lessons learned

The threat story above demonstrates the importance of controlling the access granted to low-privileged credentials, as well as remaining up-to-date with security patches. Since such attacks take advantage of existing network infrastructure, it is extremely difficult to detect these anomalous connections without the use of AI.

There was a delay of several days between the initial use of the ‘parents’ credentials and the first signs of lateral movement. This dormancy period – between compromise and the start of internal activities – is commonly seen in attacks. It likely indicates that the attacker was checking initially if their access worked, and then re-visiting the victim for further compromise once their schedule allowed for it.

Stopping a server-side attack

This compromise is reflective of many real-life intrusions: attacks cannot be easily attributed and are often conducted by sophisticated, unidentified threat actors.

Nevertheless, Darktrace managed to detect each stage of the attack cycle: initial compromise, reconnaissance, lateral movement, established foothold, and privilege escalation, and had Antigena been in active mode, it would have blocked these connections, and even prevented the initial desktop from ever exploiting the SQL vulnerability, which allowed the attacker to execute code remotely.

One day later, after seeing the power of Autonomous Response, the company decided to deploy Antigena in active mode.

Thanks to Darktrace analyst Isabel Finn for her insights on the above threat find.

Darktrace model detections:

- Device / Anomalous Nmap SMB Activity

- Device / Network Scan - Low Anomaly Score

- Device / Network Scan

- Device / ICMP Address Scan

- Device / Suspicious Network Scan Activity

- Anomalous Connection / New or Uncommon Service Control

- Device / Multiple Lateral Movement Model Breaches

- Device / New User Agent To Internal Server

- Compliance / Pastebin

- Device / Repeated Unknown RPC Service Bind Errors

- Anomalous Server Activity / Rare External from Server

- Compromise / Unusual Connections to Rare Lets Encrypt

- User / Anomalous Domain User Creation Or Addition To Group

![Pivoting off the previous event by filtering the timeline to events within the same window using timestamp: [“2026-02-18T09:09:00Z” TO “2026-02-18T09:12:00Z”].](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/69a8a18526ca3e653316a596_Screenshot%202026-03-04%20at%201.17.50%E2%80%AFPM.png)