Social engineering has become widespread in the cyber threat landscape in recent years, and the near-universal use of social media today has allowed attackers to research and target victims more effectively. Social engineering involves manipulating users to carry out actions such as revealing sensitive information like login credentials or credit card details. It can also lead to user account compromises, causing huge disruption to an organization’s digital estate.

As people use social media platforms not only for personal reasons, but also for business purposes, attackers gain information they can exploit in social engineering attacks. For example, a threat actor may attempt to impersonate a known individual or legitimate service to take advantage of a user’s established trust. This is a highly successful method of social engineering because mimicking known contacts makes it difficult for traditional security tools that rely on deny-lists to detect the attack.

In October 2022, Darktrace identified and responded to two separate malicious email campaigns in which threat actors attempted to impersonate known contacts in an effort to compromise customer devices. As it learns the normal behavior of every user in the email system, Darktrace was able to instantly detect these threats and mitigate them autonomously, preventing significant disruption to the customer networks.

Payroll Diversion Fraud Attempt Impersonating a Former Employee

While a customer in the Canadian energy sector was trialing Darktrace in October 2022, Darktrace/Email™ identified a suspicious email seemingly sent from an employee within the organization. The email was sent to the Senior Director of Human Resources (HR) with a subject line of “Change in payroll Direct Deposit.” The email requested a change in bank account information for an employee. However, Darktrace recognized that the sender was using a free mail address that contained random letters, indicating it may have been algorithmically generated. Since this incident occurred during a trial, Darktrace/Email was not configured to take action. Otherwise, it would have prevented the email from landing in the inbox. In this case though, the email went through, bypassing all other security tools in place.

Although the email was from an unknown sender, the HR director believed the email could have been legitimate as the employee who appeared to be the sender had left the organization seven days prior and no longer had access to their corporate email account. However, after reviewing it in the Darktrace/Email dashboard, the customer grew suspicious and contacted the former employee directly to verify if the request was legitimate. The former employee validated the suspicions by confirming they had sent no such email.

Further investigation by the customer revealed that the former employee had been vocal about their departure on various social media platforms. This gave threat actors valuable information to believably impersonate the former employee and defraud the organization.

Such attempts to target organizations’ HR departments and divert payroll are common tactics for cyber-criminals and are often identified by Darktrace/Email across the customer base. Darktrace/Email is able to instantly identify the indicators associated with these spoofing attempts and immediately bring them to the attention of the customer’s security team.

Using Legitimate File Sharing Service to Share a Phishing Link

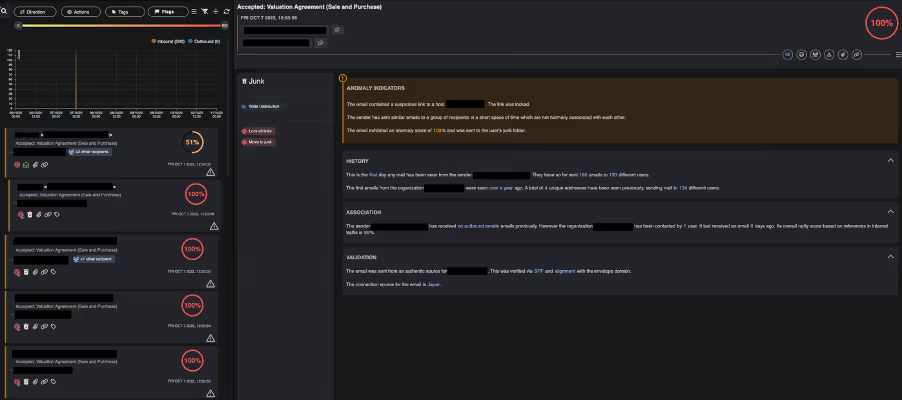

On October 7, 2022, a customer in the Singaporean construction sector was targeted by a phishing campaign attempting to impersonate a law firm known to the organization. Almost 200 employees received an email with the subject line “Accepted: Valuation Agreement.”

Four days earlier, Darktrace observed communication between another email address associated with the law firm and an employee of the customer. Darktrace/Email noted that it was the first time this correspondent had sent emails to the customer.

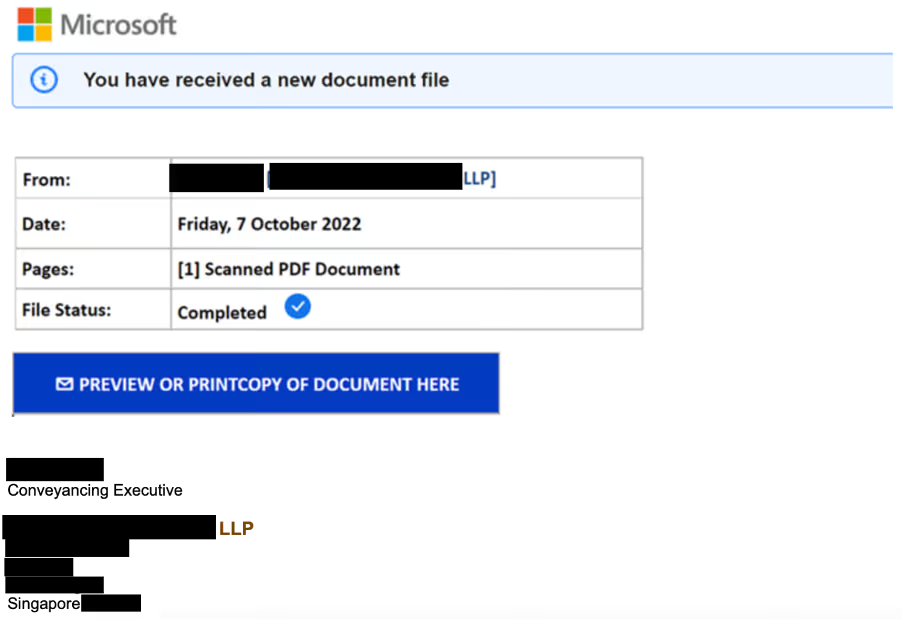

The emails contained a highly unusual link to a file sharing service, (hxxps://ssvilvensstokes[.]app[.]box[.]com/notes), hidden behind the text “PREVIEW OR PRINT COPY OF DOCUMENT HERE.” Darktrace analysts investigated this event further and found that around 30 similar URLs had been identified as suspicious using OSINT security tools in October 2022, suggesting the customer was not the only target of this phishing campaign.

Additional OSINT work revealed that the link directed to a website which appeared to host a PDF file named “Valuation Agreement.” The recipient would then be prompted to follow another link (hulking-citrine-krypton[.]glitch[.]me), again hidden behind the text “OPEN OR ACCESS DOCUMENT HERE” to view the file. Subsequently, the user would be prompted to enter their Microsoft 365 credentials.

This page contained the text “This document has been scanned for viruses by Norton Antivirus Security.” This is another example of threat actors’ employing social engineering techniques by impersonating well-known brands, such as established security vendors, to gain the trust of users and increase their likelihood of success.

It is highly probable that a real employee of the law firm had their account hijacked and that a malicious actor was exploiting it to send out these phishing emails en masse as part of a supply chain attack. In such cases, malicious actors rely on their targets’ trust of known contacts to not question departures from their normal conversations.

Darktrace was able to instantly detect multiple anomalies in these emails, despite the fact that they were seemingly sent by known correspondents. The activity detected automatically triggered model breaches associated with unexpected and visually prominent links. As a result, Darktrace/Email responded by locking the link, stopping users from being able to click it.

Darktrace subsequently identified additional emails from this sender attempting to target other recipients within the company, triggering the model breaches associated with a surge in email sending indicative of a phishing campaign. In response, Darktrace/Email autonomously acted and filed these emails as junk. As more emails were detected across the customer’s environment, the anomaly score of the sender increased and Darktrace ultimately held back over 160 malicious emails, safeguarding recipients from potential account compromise.

The following Darktrace/Email models were breached throughout the course of this phishing campaign:

- Unusual/Sender Surge

- Unusual/Undisclosed Recipients

- Antigena Anomaly

- Association/Unlikely Recipient Association

- Link/Low Link Association

- Link/Visually Prominent Link

- Link/Visually Prominent Link Unexpected For Sender

- Unusual/New Sender Wide Distribution

- Unusual/Undisclosed Recipients + New Address Known Domain

Conclusion

Social engineering plays a role in many of the major threats challenging current email cyber security, as attackers can use it to manipulate users into transferring money, revealing credentials, clicking malicious links, and more.

The above threat stories happened before language generating AI became mainstream with the release of ChatGPT in December 2022. Now, it is even easier for malicious actors to generate sophisticated social engineering emails. By using social media posts as input, social engineering emails written by generative AI can be highly targeted and produced at scale. They often avoid the flags users are trained to look for, like poor grammar and spelling mistakes, and can hide payloads or forgo them entirely.

To mitigate the risk of possible social engineering attempts, it is recommended that organizations implement social media policies that advise employees to be cautious of what they post online and enact procedures to verify if fund transfer requests are legitimate.

Yet these policies are not enough on their own. Darktrace/Email can identify suspicious email traits, whether an email is sent from a known correspondent or an unknown sender. With Self-Learning AI, it knows an organization’s users better than any impersonator could. In this way, Darktrace/Email detects anomalies within emails and neutralizes malicious components at machine-speed, stopping attacks at their earliest stages, before employees fall victim.

Appendices

List of Indicators of Compromise (IoCs)

Domain:

hxxps://ssvilvensstokes[.]app[.]box[.]com/notes/*?s=* - 1st external link (seen in email)

hxxps://hulking-citrine-krypton[.]glitch[.]me/flk.html - 2nd external link, masked behind “OPEN OR ACCESS DOCUMENT HERE”

.avif)

.avif)