Over the past few months, I’ve analyzed some of the world’s stealthiest trojan attacks like Emotet, which employ deception to bypass traditional security tools that rely on rules and signatures. Guest contributor Keith Siepel also explained how cyber AI defenses managed to catch a zero-day trojan on his firm’s network for which no such rules or signatures yet exist. Indeed, with the incidence of banking trojans having increased by 239% among our customer base last year, it appears that this kind of subterfuge is the new normal.

However, one particularly sophisticated trojan, Ursnif, takes deception a step further evidence of which we are still seeing emerge. Rather than writing executable files that contain malicious code, some of its variants instead exploit vulnerabilities inherent to a user’s own applications, essentially turning the victim’s computer against them. The result of this increasingly common technique is that — once the victim has been tricked into clicking a malicious link or duped into opening an attachment via a phishing email — Ursnif begins to ‘live off the land’, blending into the victim’s environment. And by exploiting Microsoft Office and Windows features, such as document macros, PsExec, and PowerShell scripts, Ursnif can execute commands directly from the computer’s RAM.

One of the most prevalent and destructive strains of the Gozi banking malware, Ursnif was recently placed at the center of a new campaign that saw it dramatically expand its functionality. Originally created to infect hosts with spyware in order to steal sensitive banking information and user credentials, it can now also deploy advanced ransomware like GandCrab. These new functions are aided by the elusive trojan’s aforementioned file-less capabilities, which render it invisible to many security tools and allow it to hide in plain sight within legitimate, albeit corrupted applications. Shining a light on Ursnif therefore requires AI tools that can learn to spot when these applications act abnormally:

Cyber AI detects Ursnif on multiple client networks

First campaign: February 4, 2019

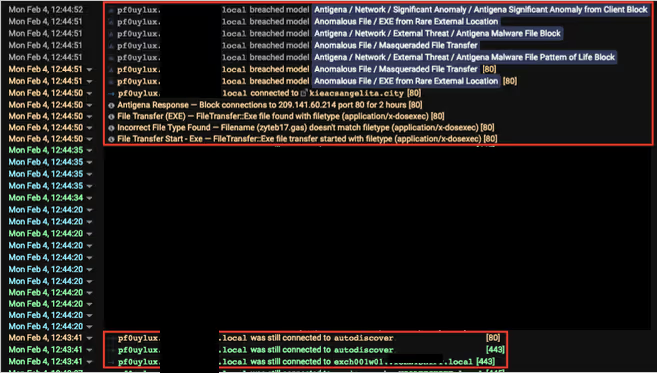

Darktrace detected the initial Ursnif compromise on a customer’s network when it caught several devices connecting to a highly unusual endpoint and subsequently downloading masqueraded files, causing Darktrace’s “Anomalous File / Masqueraded File Transfer” model to breach. Such files are often masqueraded as other file types not only to bypass traditional security measures but also to deceive users — for instance, with the intention of tricking a user into executing a file received in a malicious email by disguising it as a document.

As it happens, this Ursnif variant was a zero-day at the time Darktrace detected it, meaning that its files were unknown to antivirus vendors. But while the never-before-seen files bypassed the customer’s endpoint tools, Darktrace AI leveraged its understanding of the unique ‘pattern of life’ for every user and device in the customer’s network to flag these file downloads as threatening anomalies — without relying on signatures.

A sample of the masqueraded files initially downloaded:

File: xtex13.gas

File MIME type: application/x-dosexec

Size: 549.38 KB

Connection UID: C8SlueG1mT7VdcJ00

File: zyteb17.gas

File MIME type: application/x-dosexec

SHA-1 hash: 4ed60393575d6b47bd82eeb03629bdcb8876a73f

Size: 276.48 KB

File: File: adnaz2.gas

File MIME type: application/x-dosexec

Size: 380.93 KB

Connection UID: CmPOzP1AC4tzuuuW00

A sample of the endpoints detected:

kieacsangelita[.]city · 209.141.60[.]214

muikarellep[.]band · 46.29.167[.]73

cjasminedison[.]com · 185.120.58[.]13

Following the initial suspicious downloads, the compromised devices were further observed making regular connections to multiple rare destinations not previously seen on the affected network in a pattern of beaconing connectivity. In some cases, Darktrace marked these external destinations as suspicious when it recognized the hostnames they queried as algorithm-generated domains. High volumes of DNS requests for such domains is a common characteristic of malware infections, which use this tactic to maintain communication with C2 servers in spite of domain black-listing. In other cases, the endpoints were deemed suspicious because of their use of self-signed SSL certificates, which cyber-criminals often use because they do not require verification by a trusted authority.

In fact, the large volume of anomalous connections commonly triggered a number of Darktrace’s behavioral models, including:

Compromise / DGA Beacon

Anomalous Connection / Suspicious Self-Signed SSL

Compromise / High Volume of Connections with Beacon Score

Compromise / Beaconing Activity To Rare External Endpoint

Beaconing is a method of communication frequently seen when a compromised device attempts to relay information to its control infrastructure in order to receive further instructions. This behavior is characterized by persistent external connections to one or multiple endpoints, a pattern that was repeatedly observed for those devices that had previously downloaded malicious files from the endpoints later associated with the Ursnif campaign. While beaconing behavior to unusual destinations is not necessarily always indicative of infection, Darktrace AI concluded that, in combination with the suspicious file downloads, this type of activity represented a clear indication of compromise.

Figure 1: A device event log that shows the device had connected to internal mail servers shortly before downloading the malicious files.

Lateral movement and file-less capabilities

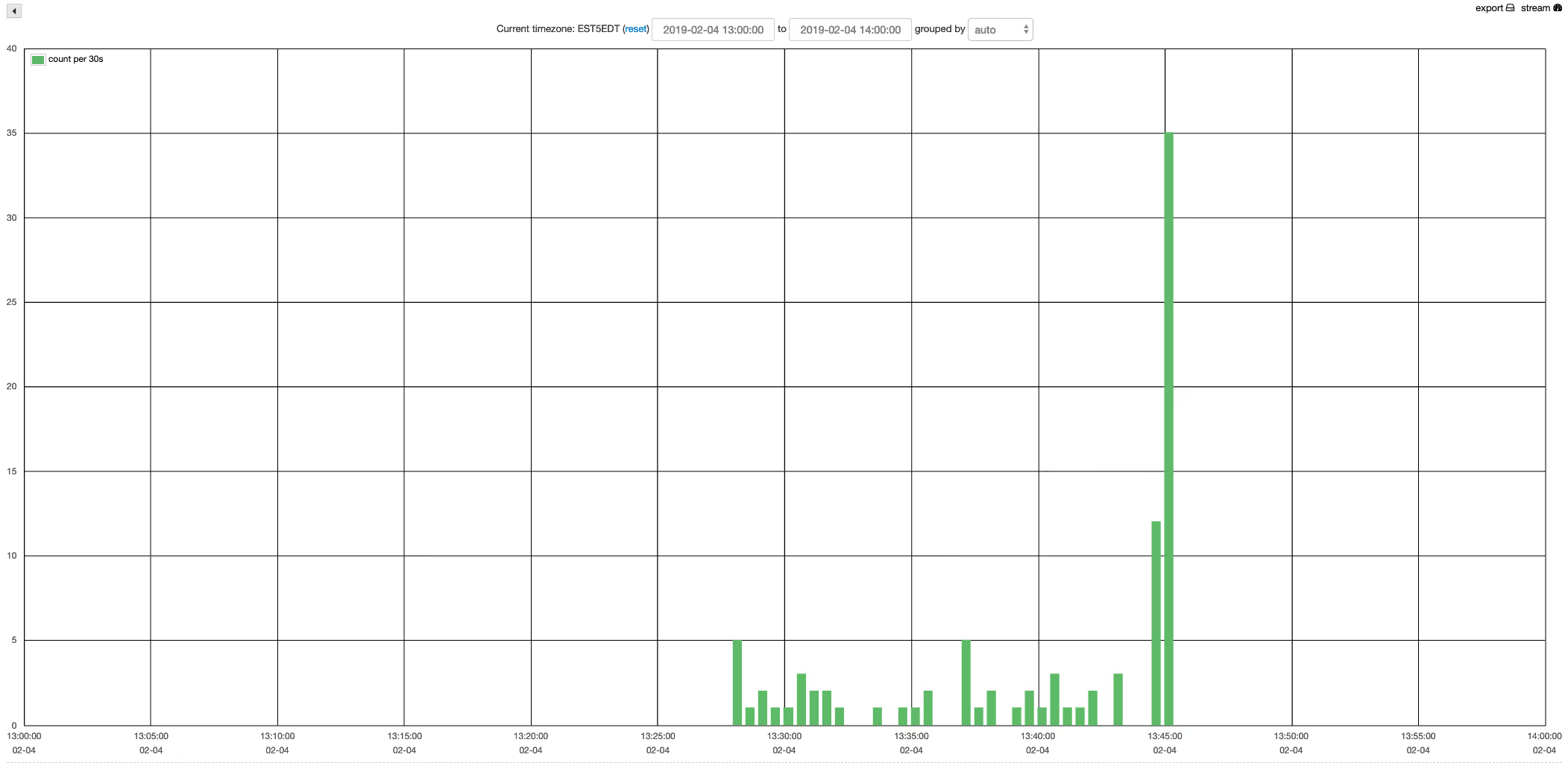

In the wake of the initial compromise, Darktrace AI also detected Ursnif’s lateral movement and file-less capabilities in real time. In the case of one infected device, an “Anomalous Connection / High Volume of New Service Control” model breach was triggered following the aforementioned suspicious activities. The device in question was flagged after making anomalous SMB connections to at least 47 other internal devices, and after accessing file shares which it had not previously connected. Subsequently, the device was observed writing to the other devices’ service control pipe – a channel used for the remote control of services. The anomalous use of these remote-control channels represent compelling examples of how Ursnif leverages its file-less capabilities to facilitate lateral movement.

Figure 2: Volume of SMB writes made to the service control pipe on internal devices by one of the infected devices, as shown on the Darktrace UI.

Although network administrators often use remote control channels for legitimate purposes, Darktrace AI considered this particular usage highly suspicious, particularly as both devices had previously breached a number of behavioral models as a result of infection.

Second campaign: March 18, 2019

A second Ursnif campaign was detected just this week. At the time of detection, no OSINT was available for the C2 servers nor the malware samples.

On a US manufacturer’s network, the initial malware download took place from: xqzuua1594[.]com/loq91/10x.php?l=mow1.jad hosted on IP 94.154.10[.]62.

Every single malware download is unique. This is indicating auto-patching or a malware factory working in the background.

Darktrace immediately identified this as another Anomalous File / Masqueraded File Transfer.

Directly after this, initial C2 was observed with the following parameters:

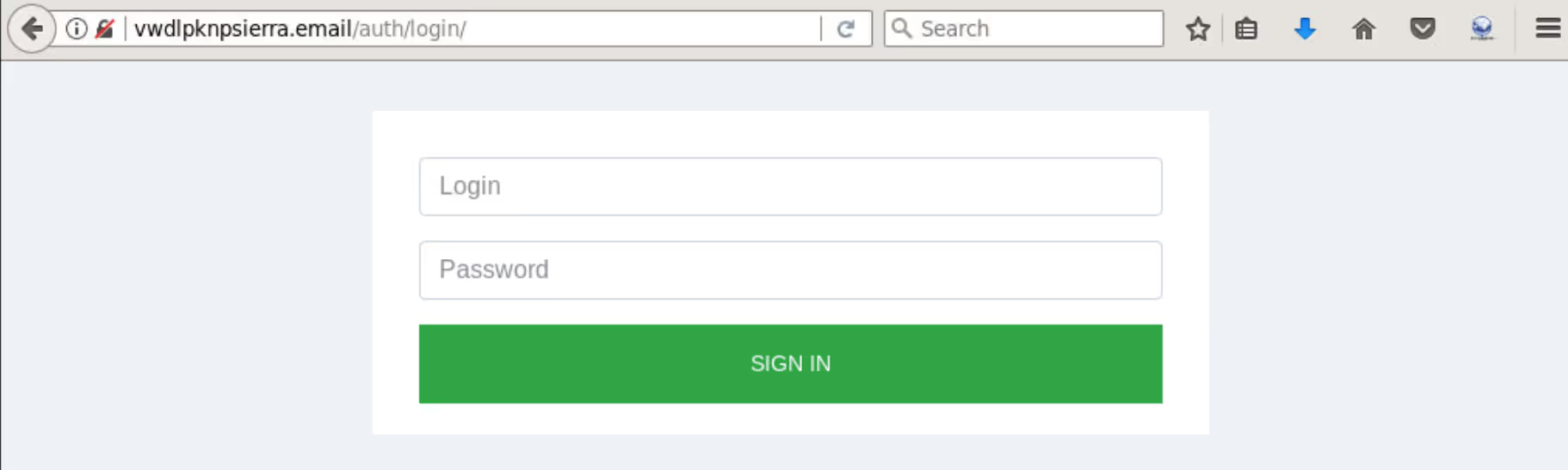

HTTP GET to: vwdlpknpsierra[.]email

Destination IP: 162.248.225[.]14

URI: /images/CKicJCsNNNfaJwX6CJ/0Ohp3OUfj/pI_2FszUK7ybqh33Qdwz/bOUeatCG2Qfks5DTzzO/H6SeiL8YozEYXKfornjfVt/hBgfcPVPCOf1H/2qo12IGl/L3B18ld4ZSx37TbdTUpALih/A5dl8FVHel/jMPIKnQfd/H.avi

User Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; WOW64; Trident/7.0; rv:11.0) like Gecko

What’s interesting here is that the C2 server provides a Sufee Admin login page:

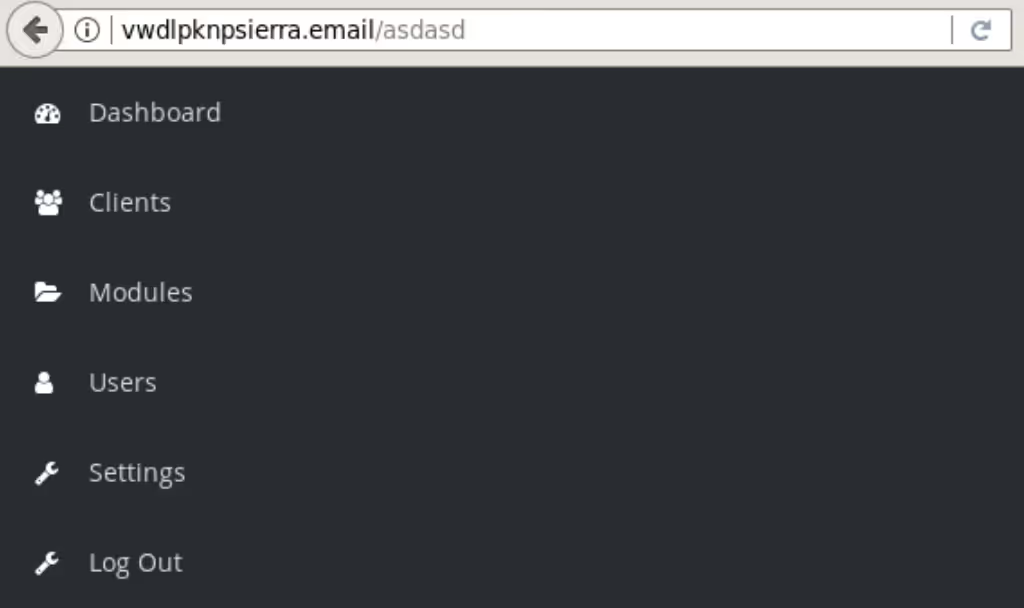

This C2 appears to have bad operational security (OPSEC) as browsing random URIs on the server reveals some of the dashboard’s contents:

The initial C2 communication was followed by sustained TCP beaconing to ksylviauudaren[.]band on 185.180.198[.]245 over port 443 with SSL encryption using a self-signed certificate. Darktrace highlighted this C2 behavior as Compromise / Sustained TCP Beaconing Activity To Rare Endpoint and Anomalous Connection / Repeated Rare External SSL Self-Signed IP.

As of the writing of this article, the domain ksylviauudaren[.]band was still not recognized in OSINT as malicious – highlighting again Darktrace’s independence of signatures and rules to catch previously unknown threats.

Conclusion

The cyber AI approach successfully detected the Ursnif infections even though the new variant of this malware was unknown to security vendors at the time. Moreover, it even managed to catch Ursnif’s file-less capabilities for lateral movement through its modelling of expected patterns of connectivity. In terms of the wider security context, the ease with which cyber AI flagged such sophisticated malware — malware which takes action by corrupting a computer’s own applications — further demonstrates that AI anomaly detection is the only way to navigate a threat landscape increasingly populated by near-invisible trojans.

IoCs

kieacsangelita[.]city · 209.141.60[.]214

muikarellep[.]band · 46.29.167[.]73

cjasminedison[.]com · 185.120.58[.]13

xqzuua1594[.]com · 94.154.10.[6]2

vwdlpknpsierra[.]email · 162.248.225[.]14

ksylviauudaren[.]band · 185.180.198[.]245