Uncategorized attacks happen frequently, with new threat groups and malware continually coming to light. Novel and known threat groups alike are changing their C2 domains, file hashes and other threat infrastructure, allowing them to avoid detection through traditional signature and rule-based techniques. Zero-day exploitation has also become increasingly apparent – a recent Mandiant report revealed that the number of identified zero-days in 2021 had dramatically increased from 2020 (80 vs 32). More specifically, the number of zero-days exploited by ransomware groups was, and continues to be, on an upward trend [1]. This trend appears to have continued into 2022. Given the unknown nature of these attacks, it is challenging to defend against them using traditional signature and rule-based approaches. Only those anomaly-based solutions functioning via deviations from normal behavior in a network, will effectively detect these threats.

It is particularly important that businesses can quickly identify threats like ransomware before the end-goal of encryption is reached. As the variety of ransomware strains increases, so do the number which are uncategorized. Whilst zero-days have recently been explored in another Darktrace blog, this blog looks at an example of a sophisticated novel ransomware attack that took place during Summer 2021 which Darktrace DETECT/Network detected ahead of it being categorized or found on popular OSINT. This occurred within the network of an East African financial organization.

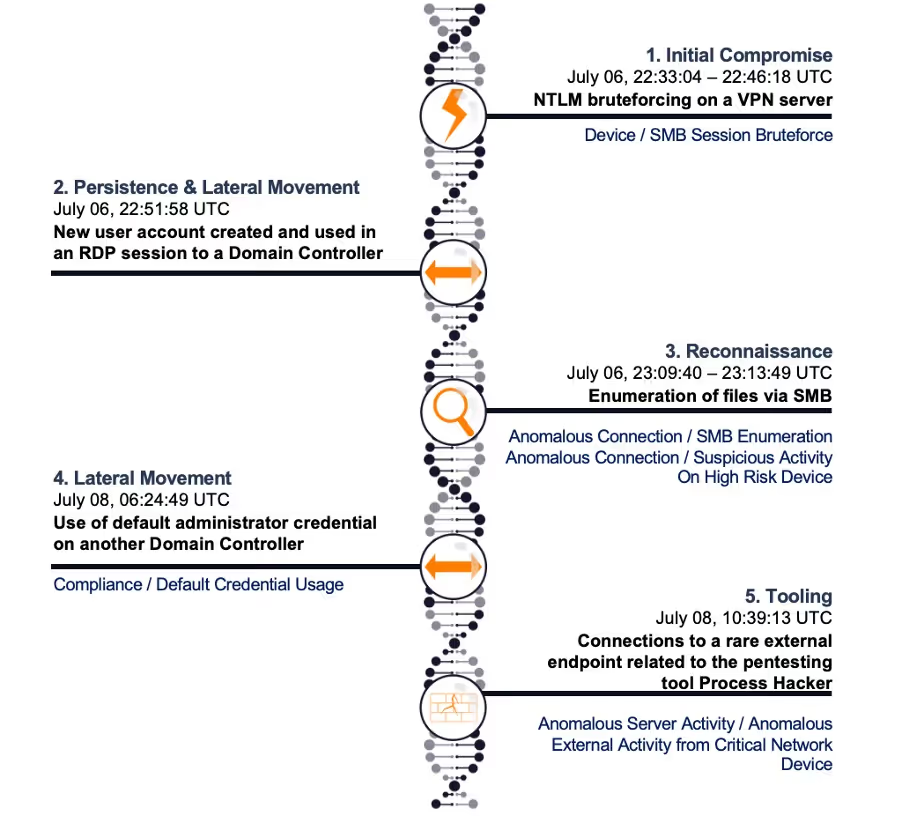

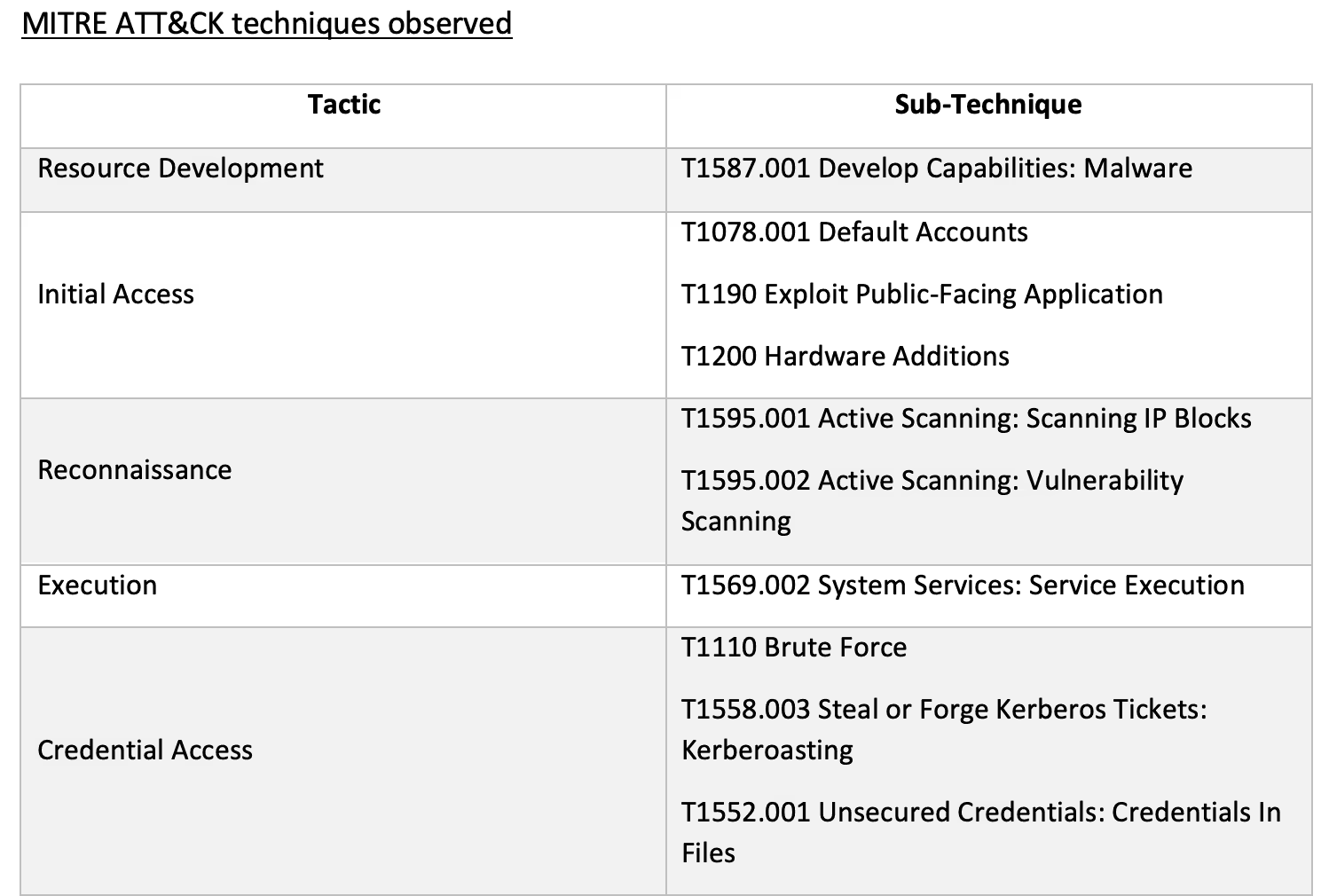

On the 6th of July 2021, multiple user accounts were brute-forced on an external-facing VPN server via NTLM. Notably this included attempted logins with the generic account ‘Administrator’. Darktrace alerted to this initial bruteforcing activity, however as similar attempts had been made against the server before, it was not treated as a high-priority threat.

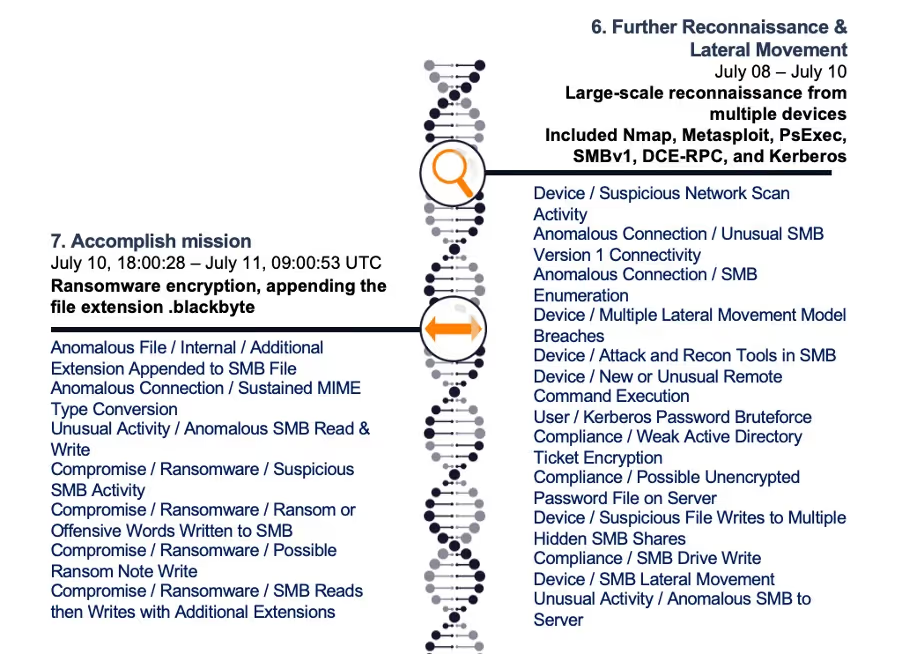

Following successful bruteforcing on the VPN, the malicious actor created a new user account which was then added to an administrative group on an Active Directory server. This new user account was subsequently used in an RDP session to an internal Domain Controller. Cyber AI Analyst picked up on the unusual nature of these administrative connections in comparison to normal activity for these devices and alerted on it (Figure 2).

Less than 20 minutes later, significant reconnaissance began on the domain controller with the new credential. This involved SMB enumeration with various file shares accessed including sensitive files such as the Security Account Manager (samr). This was followed by a two-day period of downtime where the threat actor laid low.

On the 8th of July, suspicious network behavior resumed – the default Administrator credential seen previously was also used on a second internal domain controller. Connections to a rare external IP were made by this device a few hours later. OSINT at the time suggested these connections may have been related to the use of penetration testing tools, in particular the tool Process Hacker [2].

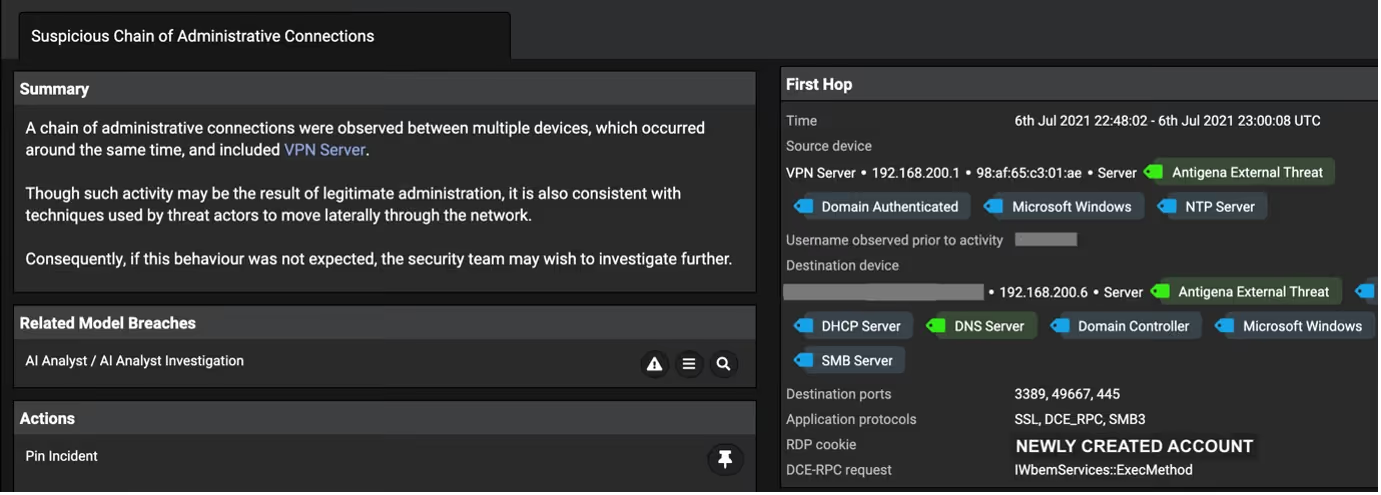

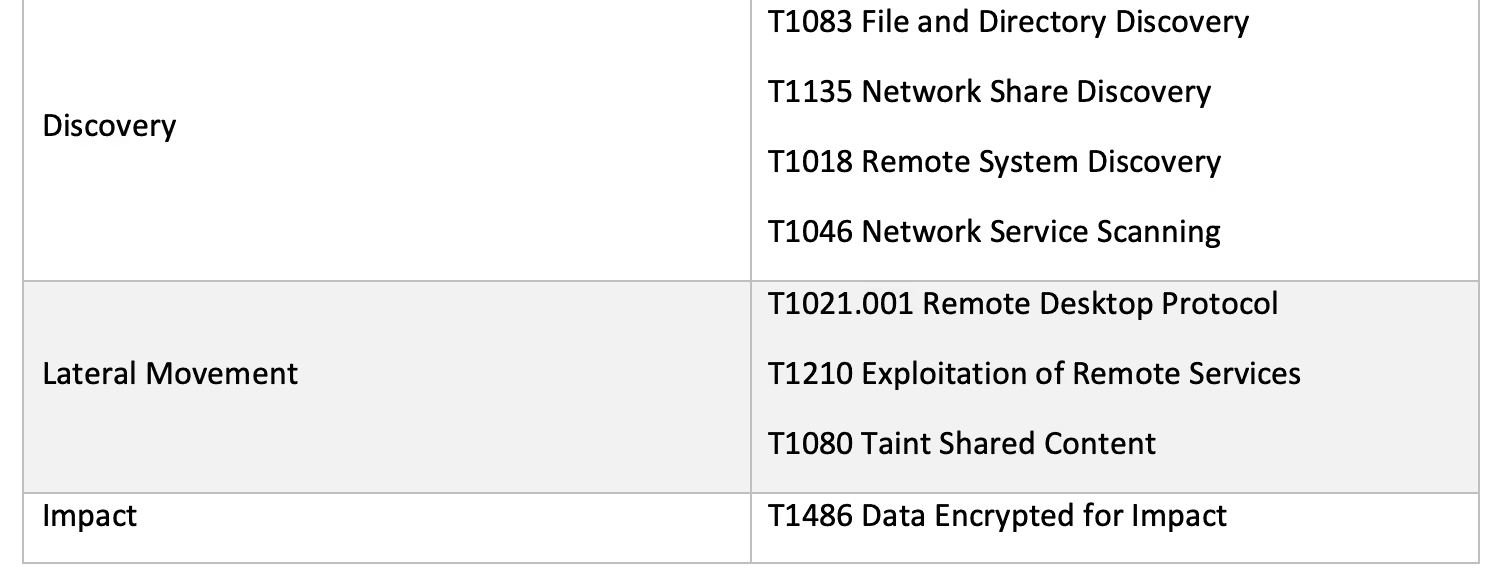

Over the next two days reconnaissance and lateral movement activities occurred on a wider scale, originating from multiple network devices. A wide variety of techniques were used during this period:

· Exploitation of legitimate administrative services such as PsExec for remote command execution.

· Taking advantage of legacy protocols still in use on the network like SMB version 1.

· Bruteforcing login attempts via Kerberos.

· The use of other penetration testing tools including Metasploit and Nmap. These were intended to probe for vulnerabilities.

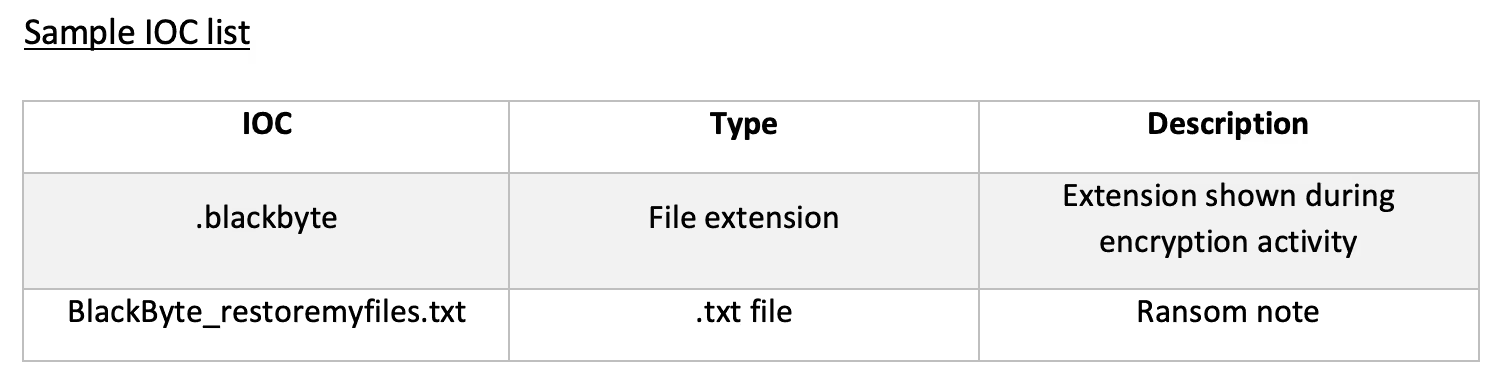

On the 10th of July, ransomware was deployed. File encryption occurred, with the extension ‘.blackbyte’ being appended to multiple files. At the time there were no OSINT references to this file extension or ransomware type, therefore any signature-based solution would have struggled to detect it. It is now apparent that BlackByte ransomware had only appeared a few weeks earlier and, since then, the Ransomware-as-a-Service group has been attacking businesses and critical infrastructure worldwide [3]. A year later they still pose an active threat.

The use of living-off-the-land techniques, popular penetration testing tools, and a novel strain of ransomware meant the attackers were able to move through the environment without giving away their presence through known malware-signatures. Although a traditional security solution would identify some of these actions, it would struggle to link these separate activities. The lack of attribution, however, had no bearing on Darktrace’s ability to detect the unusual behavior with its anomaly-based methods.

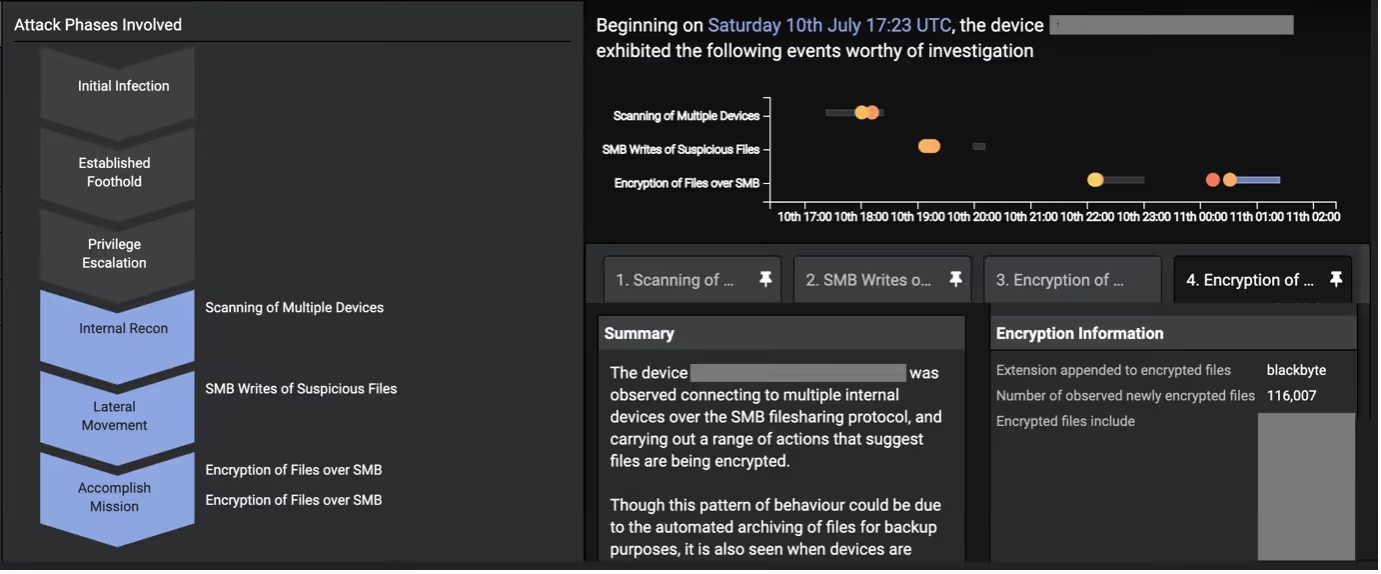

While this customer had RESPOND enabled at the time of this attack, its manual configuration meant that it was unable to act on the devices engaging in encryption. Nevertheless, a wide range of high-scoring Darktrace DETECT/Network models breached which were easily visible within the customer’s threat tray. This included multiple Enhanced Monitoring models that would have led to Proactive Threat Notifications (PTN) being alerted had the customer subscribed to the service. Whilst the attack was not prevented in this case, Darktrace analysts were able to give support to the customer via Ask the Expert (ATE), providing in-depth analysis of the compromise including a list of likely compromised devices and credentials. This helped the customer to work on post-compromise recovery effectively and ensured the ransomware had reduced impact within their environment.

Conclusion

While traditional security solutions may be able to deal well with ransomware that uses known signatures, AI is needed to spot new or unknown types of attack – a reliance on signatures will lead to these types of attack being missed.

Remediation can also be far more difficult if a victim doesn’t know how to identify the compromised devices or credentials because there are no known IOCs. Darktrace model breaches will highlight suspicious activity in each part of the cyber kill chain, whether involving a known IOC or not, helping the customer to efficiently identify areas of compromise and effectively remediate (Figure 3).

As long as threat actors continue to develop new methods of attack, the ability to detect uncategorized threats is required. As demonstrated above, Darktrace’s anomaly-based approach lends itself perfectly to detecting these novel or uncategorized threats.

Thanks to Max Heinemeyer for his contributions to this blog.

Appendices

Model Breaches

· Anomalous Connection / SMB Enumeration

· Anomalous Connection / Suspicious Activity On High Risk Device

· Anomalous Server Activity / Anomalous External Activity from Critical Network Device

· Compliance / Default Credential Usage

· Device / SMB Session Bruteforce

· Anomalous Connection / Sustained MIME Type Conversion

· Anomalous Connection / Unusual SMB Version 1 Connectivity

· Anomalous File / Internal / Additional Extension Appended to SMB File

· Compliance / Possible Unencrypted Password File on Server

· Compliance / SMB Drive Write

· Compliance / Weak Active Directory Ticket Encryption

· Compromise / Ransomware / Possible Ransom Note Write

· Compromise / Ransomware / Ransom or Offensive Words Written to SMB

· Compromise / Ransomware / SMB Reads then Writes with Additional Extensions

· Compromise / Ransomware / Suspicious SMB Activity

· Device / Attack and Recon Tools in SMB

· Device / Multiple Lateral Movement Model Breaches

· Device / New or Unusual Remote Command Execution

· Device / SMB Lateral Movement

· Device / Suspicious File Writes to Multiple Hidden SMB Shares

· Device / Suspicious Network Scan Activity

· Unusual Activity / Anomalous SMB Read & Write

· Unusual Activity / Anomalous SMB to Server

· User / Kerberos Password Bruteforce

References

[1] https://www.mandiant.com/resources/zero-days-exploited-2021

[2] https://www.virustotal.com/gui/ip-address/162.243.25.33/relations

[3] https://www.zscaler.com/blogs/security-research/analysis-blackbyte-ransomwares-go-based-variants